Lack of media access in prison is a crime

March 18, 2008

California already has a huge budget crisis, mainly due to prison overpopulation (173,000 inmates in 33 correctional institutions) and over $10 billion spent on prisons annually – a figure that now exceeds education.

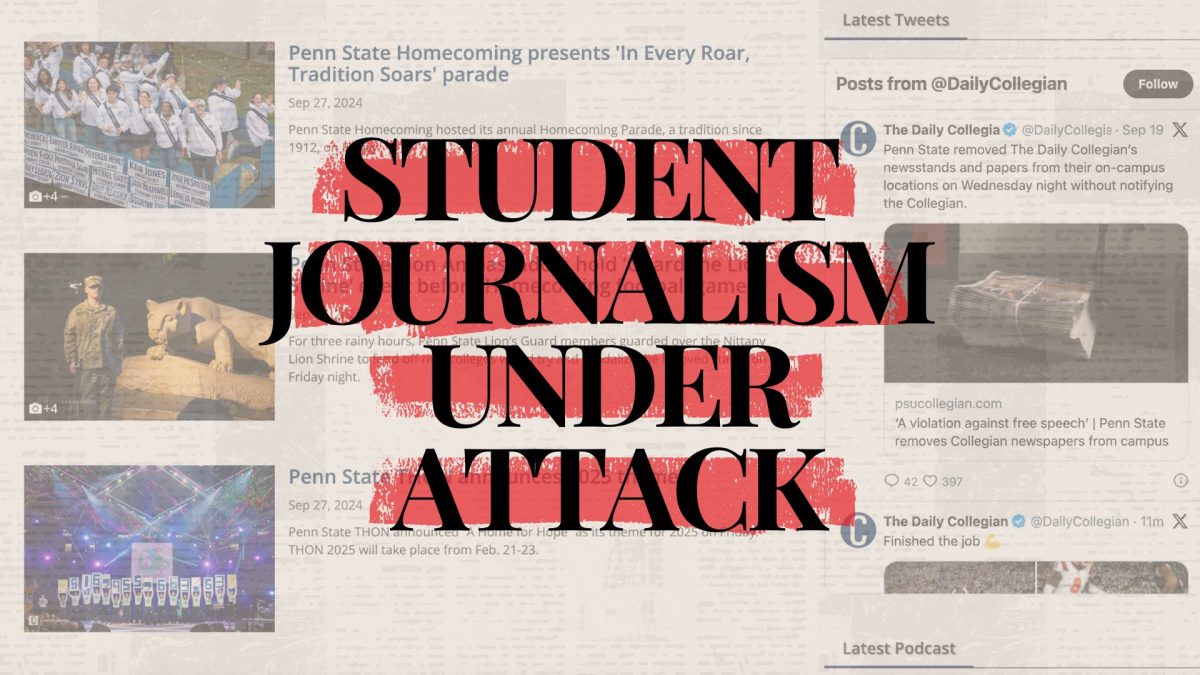

The issue of media access inside the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation is a highly debated topic and rightfully so. The California prison system is under high scrutiny right now from the federal government and is in dire need of prison reform.

In 2006, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed the Romero bill that would have allowed media to get one-on-one interviews with inmates inside prisons. Supposedly the harm in this is that victim groups believe it would allow the media to glorify prisoners and turn them into some sort of martyr for social justice, or the fight against oppression.

The daily verbal and physical abuse inflicted by officers is never reported on, because as far as the CDCR is concerned, there never was any abuse. The strongest union in the state has a stronghold on the prison system – and the taxpayer’s money.

Terry Thornton, adult operation information officer for the CDCR, says it is apparently very easy to get inside prisons now and get random interviews with inmates. The problem is that to get an interview with a specific inmate, a journalist must first get that individual’s CDCR number, contact them through the mail, (which can take weeks, even months) and then have that inmate actually WANT to respond and make a collect call to the reporter.

Not to mention that all phone calls are monitored and recorded by the CDCR.

“Journalists can also get an application to visit a specific inmate, and it doesn’t take long at all,” Thornton said. “It’s not difficult, it’s just a few more steps.”

The problem with this is that the visiting process is not quick, let alone easy. From personal experience, it can take up to six months to get approved for a prison visit from a person that is not family. For family members, it can take up to three months.

It took nearly six months for my eighth grade science teacher with no prior arrests or convictions to get in to see me. In fact, he was denied on his first application because his name was the same as someone else that had previous felony convictions.

If it is that hard for a good Samaritan teacher to get in to visit a former student and inspire him, how could it possibly be easy for media to get a visit?

Sacramento Bee reporter Andy Furillo has covered corrections on a regular basis for over 10 years. He said that it is much easier to get access to inmates inside prison now than it was 10 years ago.

“It has actually become unbelievably easy to get in,” Furillo said. “Basically, I give them a 24-hour notice, and they get me right in.”

Furillo stated that one of the biggest problems in covering corrections lies in the records of each particular institution.

“The main problem is that they still have restrictions on the books,” Furillo said. “You can usually interview anyone, anywhere, at any time, but not releasing these records gets people upset. It hurts CDCR’s public interest – like they are trying to cover something up. No way should there be restraints on the books.”

Thornton claimed that there is access to any part of the prison at any time unless there is a safety issue. If a person in the media is visiting the prison and there is a situation in which that person’s life might be in jeopardy, they will not be allowed in that particular part of the prison.

“Any area that could compromise security is off-limits,” Thornton said. “Anytime a reporter’s safety is threatened, the prison will not take them there. Otherwise, reporters are allowed to go anywhere. Even in Administrative Segregation units on a case-by-case basis, the reporter might have to wear a knife jacket, but in most cases, Ad Seg is made available to reporters.”

If a particular yard is locked down for security reasons however, Thornton explained that reporters would usually be allowed in because no inmates will be allowed in the dayroom or yard, making it an even safer situation.

“A lot of the time, reporters are just too afraid to go in and get these particular stories,” Thornton said.

Furillo disagrees and said that there are restrictions that hinder the ability of a reporter to get the full story of what is going on inside a particular prison.

“I have never spoken to a reporter that said they were too scared to go into prisons,” Furillo said. “(CDCR) has to eliminate paper restrictions. To not be able to interview inmates face-to-face is protected by these restrictions. They say you can do any random interview, but it is hard to get outside of those restrictions.”

Reporters on probation or parole are not allowed to get into the prison for interviews. However, if the offense took place long enough ago, the warden is allowed to make exceptions.

“It is a case-by-case situation,” Thornton said. “Sometimes having a prior record can hinder a reporter from getting in. I’m not saying it’s impossible, but the longer you are offense-free, the better chance you have of getting in.”

Thornton went on to say that an easier way for ex-cons to get behind the walls and talk to inmates is through prison ministry or some sort of faith-based religious organization designed to mentor and help inmates.

The discrepancy here is – why is it easier for an ex-con that is part of a religious group to get inside the prison and volunteer than an ex-con journalist working for a credible news organization to get inside and expose some real truth?

Another area for legitimate concern is that the CDCR’s medical facilities are currently under federal court receivership for poor treatment of patients and unsatisfactory conditions for inmates. These medical records are still not being released to journalists.

“Reporters can view the medical facilities, and staff will discuss medical issues with them,” Thornton said. “Reporters don’t get to interview mental health patients, due to their possible lack of mental health. Since we are under federal receivership right now, everyone abides by these rules.”

It is these rules that are so problematic. CDCR doesn’t want to release these records or let reporters talk to mental health patients incarcerated because countless stories would come out about abuse, neglect, corruption and flat out poor medical treatment.

Levi Cardiff, a former inmate at High Desert State Prison, feels strongly about the issue.

Recently off parole and raising a family, Cardiff was sent to prison in horrific physical condition. After being shot, he lost his kidney, his spleen and a large amount of his small intestine. This forced him to have to wear a colostomy bag.

It was in prison where he saw the true injustice of California’s judicial system and correctional facilities.

“The medical facilities are so unorganized you can come into the prison with a s—bag, and there won’t be any bags available to change it. So instead, you re-use the bag and clean it yourself in the general population. If that type of story got out into the media, the prison would have to reform in more ways than just medically.”

These are the types of stories that must be reported on. Without the possibility for a reporter to access inmates one-on-one and get these stories, nothing will change because the CDCR will continue to keep medical and inmate records under wraps.

“(CDCR) won’t release medical records because they are so screwed up,” said Cardiff. “It can take weeks, months, even years to get urgent operations done while inside. Even if reporters were allowed to see these records, it wouldn’t matter because the system is too corrupt. There is no way that those records will ever be released.”

Furillo believes that some of the media coverage on prisons has had a huge impact. He also believes it is the future toward reforming a California prison system that is in the worst shape in the country.

“The Orange County Register did a story on the shooting policies at Corcoran State Prison about 10 years ago,” Furillo said. “More and more inmates were being shot and killed by officers, and the paper’s stories drew a lot of attention to that. The CDCR eventually changed its shooting policies.”

Cardiff and Furillo both believe that with more media coverage and access to certain inmates that have real knowledge about what is going on inside the prison, it could change things.

“Reporters never came into the prison when I was incarcerated — not once,” Cardiff said. “If reporters had come in and talked to me, or many other inmates with similar situations, there would have to be a change.”

Cardiff said that if reporters came into the prison more, pre-release classes would have to be documented. As of right now, pre-release classes are there to prepare inmates for getting back into society. All of these classes are nothing but a formality. There is no actual education or help provided to inmates.

“With more reform, I wouldn’t have been able to go without pain medication for so long while I was still in a wheelchair,” Cardiff said. “Inmates that are sick and never see the sun or fresh air have no chance. Half of the prison population has Hepatitis C! It’s a hazard for everybody that is locked up. When a building is already full and you fill it up again with the same amount of people, it is a recipe for disaster.”

Prisons are so overpopulated right now that many inmates are sleeping on bunks out in the open of former gymnasiums or reception areas. This gives inmates no privacy, and when the bunks are stacked on top of each other three high, it creates tension, and the possibility for violence rises to the next degree.

“It depends on the story, but journalists have access to these overcrowded gyms and dayrooms,” Thornton said.

Once again, it always depends on what the prison wants journalists or reporters to see. Reporters aren’t there everyday. Reporters get limited access to everything inside the prison, no matter what the CDCR wants to tell you.

Cardiff believes that the media has to have access to prisons, or nothing will improve.

“The CDCR is the biggest gang in California,” Cardiff said. “They, in a sense, create more organized crime within their walls through racism, violence and the lack of access to education. CDCR is the biggest leader in organized crime in the state.”

Galen Kusic can be reached at [email protected].