Anti-Rape devices: Do we need them?

December 8, 2014

The sun is set by the time your night class has ended, and you are walking to your car alone in the dark. Your keys are gripped tightly in the palm of your hand and you are cognizant of anyone that passes you by.

This is a scene a number of women can relate to.

“As a woman walking alone at night, it’s like this anxiety I have. My first thought is what do I have on me to defend myself,” said Alejandra Fernandez Garcia, 24, a double major in sociology and ethnic studies. “I usually carry pepper spray and I hope that I don’t have to use it. I have my car keys in my hand and try to walk where there’s people around. Basically, I feel like I have to be hyper aware of my surroundings.”

This anxiety derives from the very real and very daunting possibility of receiving unwanted advances.

According to The Washington Post, 55 percent of 1,570 colleges and universities with 1,000 or more students received at least one report of a forcible sex offense on campus in 2012.

In recent years, there has been a variety of inventions to aid women in preventing sexual assault. Such examples include date rape drug-detecting nail polish, the SafeTrek application for smartphones which allows the user to hold a button and alert police of their name and location if they let go without entering their pin number and tear and pull resistant undergarments that are advertised as “anti-rape underwear.”

These devices have received mixed reactions from students.

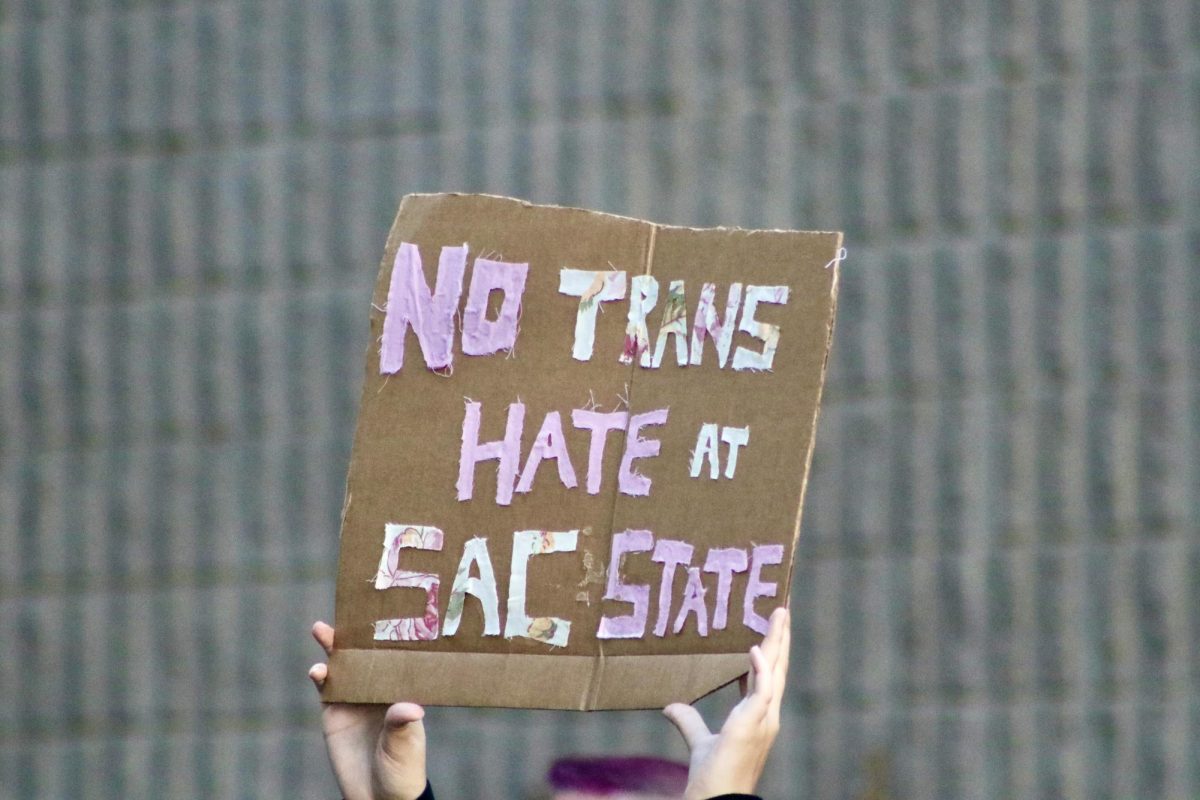

“I think for women, you know, having these types of things available to us, I still think it cultivates this hyper anxiety,” Fernandez Garcia said. “The very fact that I should even have to have these things to feel safe is so ridiculous. There’s a lot of wrongly-placed victim blaming on why these things are happening.”

While students make it clear they are not denying that these are important tools for safety to have, they are discussing the reality of why these inventions needed to be created in the first place.

“Honestly, I think it’s sad we need those things,” said Juan Chavez, 22, a theater major. “I mean, I’m glad there are more ways to take precautions now, but it’s really sad that protecting yourself is such a huge industry. The way things are right now, it’s just really frustrating — and this is a man talking, so I can imagine how worse it must be for women.”

The Jeanne Clery Act Report is an annual release of crime statistics including sexual assault for college campuses. The report, which can be accessed online, also links to various brochures. Among these is a sexual assault fact sheet created by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

It includes a list of 17 tips for lowering women’s risk of being assaulted. While this is helpful information, the focus on preventative measures brings up a point argued by students: the responsibility of deterring sexual assault is shown to lie with the potential victims, not the assailants.

“Every time somebody says, ‘Well, what did she do?’ Every time somebody tries to pass the blame onto the victim, it just makes me mad. It’s despicable, you know?” Chavez said. “I think that comes from a place of not wanting to look inward and say, ‘Maybe I am part of the problem. Even if I have not actively hurt somebody, maybe I just passively accepted it at some point,’ and that’s adding to the problem, in my opinion.”

There are people who have dedicated their life’s work to addressing this issue.

Women’s self-defense instructor Midge Marino, 76, has been teaching classes at Sacramento State since 1973. In an interview last year, she spoke of what she called “pink and blue socialization,” where society places males and females into certain gender roles. Marino said these molds teach norms which leave men responsible of protection and women instructed on how to behave to avoid assault.

“Women are taught to be afraid—to keep their head down and oh, ‘Don’t dress like that. Don’t say that. Don’t go there at night,’” said Marino said. “Our society teaches women to not get attacked instead of teaching cowards not to attack us.”

Marino, whose background is in judo, said she was inspired to teach students not only how to physically protect themselves, but, after seeing a demand for education, the facts of gender roles and sexual assault as well.

“But what if the man can’t be there? Then they’d feel bad, and the woman won’t know what to do,” Marino said. “I thought, ‘Well, why aren’t we teaching our women that it’s okay to learn to protect yourself?’”

Students weigh in on where they think the difference in how women and men can feel about walking alone at night comes from.

“I feel like that’s part of male privilege,” Fernandez Garcia said. “Granted, I’m not saying men don’t get mugged or assaulted or jumped, but there’s a certain privilege that comes with being male that you don’t necessarily have to worry that if you’re alone you’re going to be someone’s target.”

Both Chavez and Fernandez Garcia bring up that while harassment and sexual assault is not solely something that women experience, they address how women can be regarded in a way that makes an experience as simple as walking to their cars or to the light rail station to head home a potentially dangerous one.

“I can only speculate never having been a woman, but I would imagine it’s really scary,” Chavez said. “Because there’s so many things that can happen to you and you never really know who is capable of doing something to you. It must be so frustrating to never be able to be at ease like at night by yourself, really anywhere now; there’s nowhere that’s completely safe for women.”

Chavez said he usually leaves campus late at night and feels relatively safe walking alone. This is not a sentiment he shares when it comes to his girlfriend. He recognized how common it is for strangers to approach women on the street.

“I can probably count on one hand the times in my life where somebody has tried to rob me or intimidate me. It has happened, but not a whole lot and not in a while. But I know for a fact it’s way worse for women,” Chavez said. “Like with [my girlfriend], if it’s late and I’m tired and she wants to walk back to her dorm by herself, she’ll be like, ‘well, just let me walk,’ and I’ll be like, ‘no [expletive] way.’ I don’t want her to walk anywhere at night because I’m so afraid. I fear for her safety. Even if I’m tired or whatever, I’ll drive her. That’s just the way it is, unfortunately.”

There is a tactic some women’s movements have in appealing to society’s empathy and get people involved against rape and dissuade victim-blaming by reminding people that victims could be the women in their life: their sister, girlfriend or mother.

This is a concept some agree with and find effective, while others question it.

“I think sexual assault against women is very normalized, and when it’s normalized people don’t crituque or challenge it, and so I hear a lot of the time, ‘oh you know think of your mother or sister or friend being assaulted,'” Fernandez Garcia said. “A critique I have on that sometimes is why can’t society regard us human beings? Regardless of our roles as a mother, sister, et cetera — our lives matter. Does anyone have to be regarded as a man’s sister or mother to be regarded as valuable?”

Fernandez Garcia advocates for education and values the classes, communities and resource centers on campus that have aided in her awareness of women’s issues.

Resources on campus include the Women’s Resource and PRIDE Center and the Multi-Cultural Center, as well as the Student Health Counseling Services in The Well that offers counseling and healthcare services for victims of sexual assault.

While both Chavez and Fernandez Garcia comment on society’s need for what are essentially anti-rape inventions, they do recognize why they were created and their value.

“I would use the [SafeTrek] app, and I am grateful that such things exist, but again it’s like how many defense tools we have to make until we start addressing the male root of the issue?” Fernandez Garcia said. “I feel like there has to be a completely global, cultural shift in the way women are viewed. And I’m still chewing on that like, ‘how can we make everybody care?’ because there are even some women who don’t think this is an issue.”

While Fernandez Garcia is unsure whether sexual assault will ever be a non-issue and if these inventions are truly effective, she hopes it will and, like Marino, she is inspired to be a part of that change.

“i have to keep believing that things are still going to keep pushing forward. Maybe when I’m 90 years old, I can look back and say things have shifted and I want to have been a part of that,” Fernandez Garcia said. “Maybe I’ll make that my mission in life: figuring out a way to stop violence against women.”