University investigates donor’s racism

September 24, 2004

By some accounts, Charles Goethe (pronounced Gay-tee) was just a wealthy Sacramento resident interested in funding good works, which is why he left huge sums of money to Sacramento State after his death in 1966.

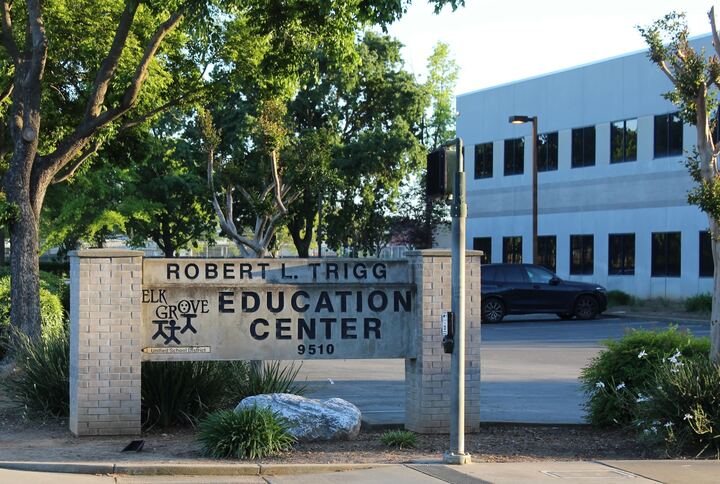

The arboretum near the J street campus entrance is named in Goethe’s honor, and faculty still receive research grants from the money Goethe left to the university.

According to others, including Professor Emeritus of Social Work Tony Platt, Goethe was a racist, a proponent of eugenics, a pro-Nazi anti-Semite who spent most of his life supporting white supremacy.

Platt said he discovered this other side to Goethe while doing research projects on the American eugenics movement, a long discredited science of the 1920s and ’30s, that believed human characteristics were based mostly on one’s race, and whose right-wing supporters advocated keeping racial strains “pure” through selective sterilization of “undesirables,” severe restrictions on immigration, and bans on interracial marriage.

Dr. Platt presented his findings in a February 2004 report titled “What’s In a Name? Charles M. Goethe, American Eugenics, & Sacramento State University,” and in a public lecture February 24, 2004, in the Hinde Auditorium.

And then, silence.

Six months later, Platt said he has heard nothing, “not one word.” He has received no response from the university, from Sac State President Alexander Gonzalez, or from the CSUS Foundation — which figures prominently in the report.

“I was expecting some sort of polite, something. At least,” said Platt in a recent interview.

Because of the university’s lack of response, Platt wrote “An Open Letter to President Gonzalez,” dated Sept. 1 and sent to Gonzalez, the CSUS Foundation, and the State Hornet, among others.

Platt’s letter urges Gonzalez to respond to the concerns raised by the report, to publicly confront the controversial legacy of Goethe, and to investigate the early relationship between the university and Goethe, in particular the large bequests Goethe made the university in his will.

“If I were in (Gonzalez’s) situation,” said Platt, “I would set up a special committee of the university, and I would draw upon different sectors of the university so it includes staff, and faculty, and students, and administration, to talk through what to do about the situation, because there’s lots of different aspects of it.”

However, President Gonzalez said that the university is looking into some of Platt’s recommendations. Gonzalez says he wants “to get the facts straight” before responding to either Platt or to the Sac State community.

Gonzalez said he has assembled a task force at the Foundation to look into the money Goethe left to Sac State, and what the university can legally do with those funds. Gonzalez hopes to a have a report from this task force soon.

“We accepted his bequest, so we’re involved legally and financially,” Gonzalez said. “So what I’m trying to do right now, what the Foundation is trying to do, is assess what that really means. How much money is left, who the trustee is, what (Goethe) left the money for.”

Gonzalez’s concerns are chiefly about the Goethe money.

“I’m a psychologist by training, so I know about the eugenics movement,” Gonzalez said, when asked about Platt’s description of Goethe as a supporter of eugenics. “We’re judging a person in 2004 on our standards about something that occurred at the turn of the century. It’s easy to see in hindsight, but when it was going on it was an accepted theory.”

According to Platt’s report, however, Goethe was not just a supporter of scientific eugenics, but was a racist who wrote thousands of letters and published hundreds of pamphlets in support of his views.

Platt’s report says that Goethe led campaigns to restrict immigration from Latin America and supported the forced sterilization of society’s “undesirables.” Platt also wrote that Goethe funded anti-Asian campaigns and praised the Nazis before and after World War II. The report also states that Goethe practiced discrimination in his own business dealings, refusing to sell real estate to Mexicans and Asians.

Platt found that Goethe’s last recorded donation, three months before he died in 1966, was to the Northern League, a group dedicated to bringing “Nordic peoples” together against the “worthless peoples of Africa and Asia.”

“How does that relate to the University?” Gonzalez said when asked about the racist characterization of Goethe. “I can only address the remaining trust that the University accepted.”

Platt disagrees.

“I would hope that CSUS would take a broader view of its ethical responsibility. Doesn’t the university have a moral obligation to repudiate Goethe’s racism, which did extraordinary damage to many communities — sterilization of poor women without their consent, racist real estate policies, anti-immigrant legislation?

“Shouldn’t the university accurately describe Goethe in CSUS markers, plaques, Web sites, official documents, and publications? Doesn’t CSUS have a responsibility to establish guidelines about accepting donations from individuals and organizations whose values and practices are antithetical to CSUS?”

Platt is convinced that Sac State has deliberately tried to erase any controversial aspects of Goethe from the history of the university. Through what Platt calls “strategic amnesia,” the school praises Goethe’s gifts while remaining silent about his racism.

“I think the way they dealt with the Julia Morgan House (where Goethe lived in Sacramento most of his life, and is now administered by the university) was to try to erase Goethe. Anybody visiting that place not knowing about him might think this is all about Julia Morgan, that Goethe actually never lived there. They clearly did that, in a way, to sanitize the university’s reputation and try to do away with some of the more distasteful aspects of Goethe’s life, by renaming it and so on.”

Platt said that he found evidence that Goethe’s personal library, full of books and pamphlets on eugenics, with Goethe’s notations in the margins, had been secretly sold by Sac State after Goethe’s death. Platt interviewed the auctioneer hired by the university to sell Goethe’s belongings, who said “The university didn’t want us to sell (the library) in Sacramento,” because Goethe’s personal notes were so offensive. “Somebody at the college didn’t want the collection available here to be researched.”

“Those are strong accusations,” Gonzalez said, “and they have to be based in fact. I don’t know if they are or not.”Platt defended his research on the subject.

“My critique of the university’s handling of the Goethe bequest is the result of months of research and interviews,” Platt said. “The research verifies the findings with extensive sources and documentation, available for anybody to review.”

Still, both Gonzalez and Platt agree that the Goethe legacy is complex. Gonzalez said he will wait for his task force’s findings before proceeding.

“Once I get that, then I can go back and say look, here’s what’s left, this is what’s been operating, here are the loans that have been made, and then I can say the next step is going to be X,” Gonzalez said.Platt hopes that the discussion about Goethe will become public and transparent.

“I would be very willing to meet with the Task Force to explain and discuss the findings in my report,” Platt said. “I hope that the results of the investigation will be made available to the campus community.”