TESTIMONIAL: Sac State needs to recognize the visibility of Native students on campus

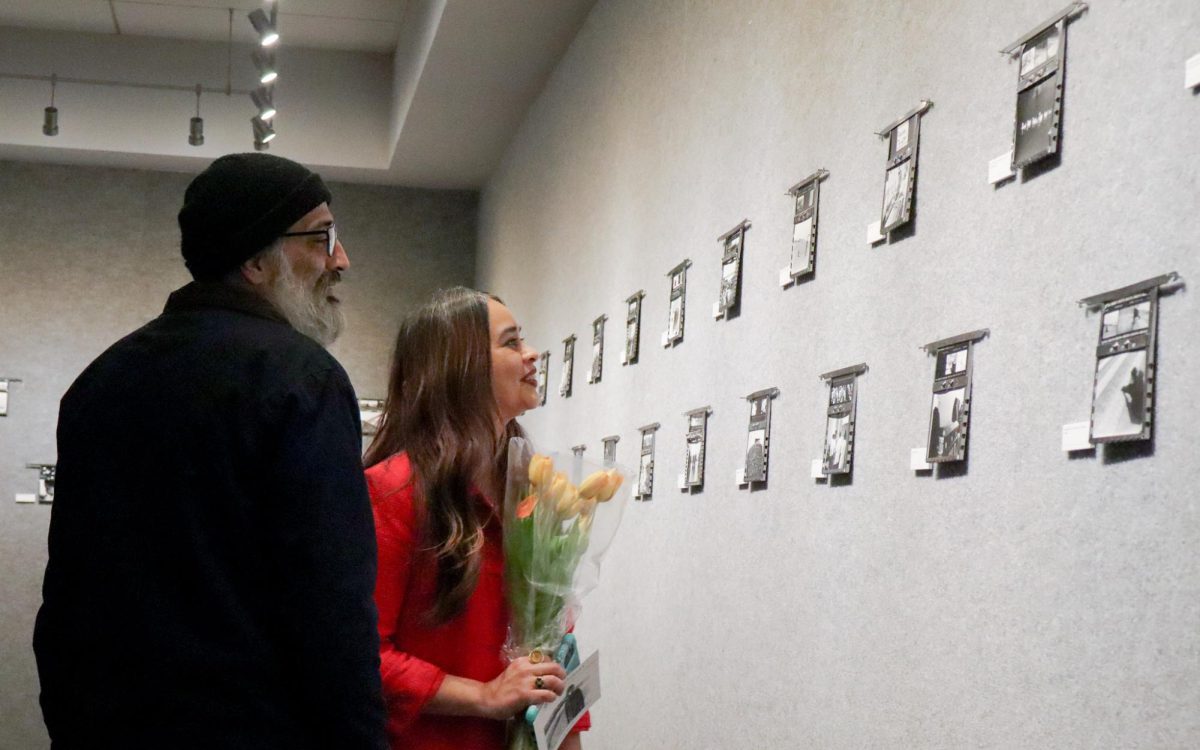

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion editor Emma Hall writes about her experience being a Native student at Sacramento State. One of 73 Native students in total, Hall says Native students often experience isolation. (Photo courtesy of Hall).

November 1, 2021

Since I can remember, I’ve been the only Native American student in the classroom.

I am Cherokee and Blackfeet by descent, and being born and raised in Contra Costa County, where Native Americans make up 1.0% of the county’s overall population, meant I often felt isolated and erased. No one looked like me or came from the same background.

During my junior year of high school, I spoke about Standing Rock to my history class for a presentation. It was 2016 and thousands were protesting the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, an oil pipeline that ran through the Standing Rock Reservation, threatening the tribe’s water.

As I stood in front of my peers, I remember talking about protestors being chased down by dogs and pepper sprayed, how they were beaten by police, citing the abuse caught on video and how protestors were held in dog kennels. But my classmates didn’t care. They looked at me disinterested, some were even scrolling through Snapchat on their phones. My passion was met with callousness.

For my classmates, the abuse at Standing Rock didn’t affect them, so why should they care? Native people were a thing of the past in their eyes. Even though I stood in front of them as a Native person, ignorance taught them that Native people were completely wiped out from genocide. Despite this, I never gave up on talking about the rights of my people, but I knew that because of my lone voice, I had to work harder to fight for change.

Moving to Sacramento and attending Sacramento State, I feel the same feeling. At Sac State, I am one of 73 Native students, according to university demographics. Despite us being the smallest ethnic group on campus, students like me still exist. Yet, the university offers very little support to Native students, with the exception of the Native Scholars and Transition Program.

When Sac State decided to not remove Columbus Day from their university calendar and slotted it next to Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I felt that the institution I chose to attend didn’t care about how Native students were impacted by this decision.

For context, many, if not all of Columbus’s atrocities targeted Indigenous people. For example, he and his 1,200 men raped and sex trafficked countless Native women and children, some as young as 9-years-old according to Indian Country Today. This is who Sac State chooses to honor, despite almost everyone, including the White House choosing to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day over Columbus.

On Oct. 11, President Robert Nelsen stated in an email that the university is “examin[ing] the possibility of making the official change” only after a Native club on campus, Ensuring Native Indians Traditions spoke with the Associated Students Inc. at Sac State asking the university to change the name.

Yet, in the same email, Native people are continuously referred to as if we’re a thing of the past. It’s excerpts from this email saying “we celebrate Indigenous People’s Day [to] remember and honor the original native people of this nation,” that erase the presence of Native students on campus.

What is there to ‘remember’ if Native people attend Sac State? We’re still here and this narrative encourages the notion that we no longer exist. How Sac State speaks about Native issues and Native students cannot be an afterthought.

Verbiage like this results in Native students experiencing erasure and disregards us as a part of Sac State’s community.

It wasn’t until I met other Native students that I realized these factors were a trend among us that result in feelings of isolation and intense loneliness. This is because universities fail to recognize us as individuals, and instead, we’re forced to turn to Native faculty, other Native students, or remain alone. At Sac State, the Native student to faculty ratio is 4:1.

My experiences as a Native woman drove me to pursue journalism and call for change to help Indigenous communities.

While interviewing Native students for a journalism project, I heard my own obstacles within their stories. They experienced isolation, struggles with their identity and the same incidences of microaggression and racism I also faced in my life overall. As journalists, the old guard tells us to separate ourselves from the story. Yet, talking to these students was like looking into a mirror. It made my reporting stronger because I understood their obstacles firsthand.

When I’m asked, “why journalism?” I say it’s because I’m too angry at the world to stay quiet. If we’re being specific, my anger is rooted in the struggles of my people.

It’s the stories from protests at Standing Rock that drive my passion to platform Native issues. It’s the thousands of Native women and girls who are kidnapped, murdered, and sexually assaulted each year that fuel my anger to push for change. It’s the stories of Native activists taking back Alcatraz in the late 1960s that remind me of how the past generations of Native folks fought for change.

It’s my own experiences and stubbornness that taught me operational anger. While my experiences are personal, they aren’t isolated incidents. Everyday I am reminded that my obstacles are bigger than myself, but as a journalist, I am dedicated to uplifting the stories for not just Native people, but to make an impact for the communities I serve, including my own.

Lawrence Murray • Feb 14, 2022 at 9:31 am

Thank you for sharing. As one of the Native students, I found help in several support groups like MESA, SacStare Dems, tutoring, and from professors. But I was very discouraged about Sac State having another Columbus day.