The California State University will be raising tuition this fall even as the California State Auditor accuses it of financial mismanagement — specifically of not being able to justify pay increases and growth among management personnel.

This kind of behavior shows a complete lack of shame on the part of the CSU administrators, and demands that they learn a lesson of their own on financial responsibility.

When they voted to raise tuition by $270 annually for in-state undergraduates in March, members of the CSU Board of Trustees said that a tuition increase was necessary because they needed to fill a $168 million funding shortfall between what they requested from the state and Governor Jerry Brown’s budget proposal.

Pro-increase trustees brought out Graduation Initiative 2025 as a main reason for increasing costs, saying that the money was needed to help more students earn degrees from system schools.

The tuition increase passed, but only weeks later the State Auditor released a scathing report detailing financial mismanagement throughout the system.

The auditor found that financial compensation for CSU management as a whole “significantly outpaced” raises in the salaries of other groups of employees — a situation which prevails at Sacramento State, where total management pay rose while total faculty pay declined.

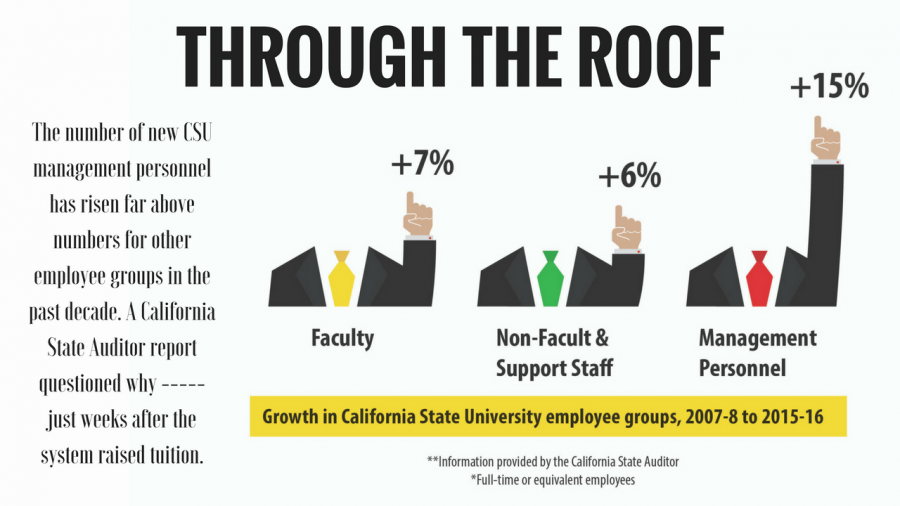

According to the report, the number of administrative positions in the system as a whole grew 15 percent over the past decade, while the number of FTE faculty grew by 7 percent and the number of FTE non-faculty support staff grew by 6 percent.

Meanwhile, the six campuses visited by the auditors often could not justify the administrative glut and “one campus (Cal Poly San Luis Obispo) granted raises to management personnel that were not supported by current written performance appraisals, as required by CSU policy,” California State Auditor Elaine Howle said.

It ought to be common sense that the Board of Trustees shouldn’t ask students to bear the burden of increased tuition for the first time in six years just as the system receives a scathing report from the state about the money it already has.

As Assemblywoman Sharon Quirk-Silva, D-Fullerton, said in an interview with The State Hornet last month, colleges need to rethink what they do with the money that they have before they increase burdens on others.

“Sometimes we’ve heard about college presidents making over $350,000 per year,” Quirk-Silva said. “Are there ways to save on administration?”

But the problem of increasing tuition paying for an expanding administration is nothing new.

According to an analysis by Cal Poly Pomona professor Ralph Westfall, the number of full-time faculty positions in the CSU system rose 3.5 percent between 1975 and 2008 — but the number of administrative positions rose 221 percent and tuition went from virtually non-existent to $2,272 in the same time period.

Of course, administrative glut isn’t the only rising cost that students pay for with tuition increases. And administrators or their defenders might argue that more populous student bodies facilitate the need for the existence of these positions.

Yet although the number of CSU administrative positions rose 15 percent from 2007-08 to 2015-16, the number of total students enrolled in the system only rose by 9 percent, according to CSU statistics. Meanwhile, there are less faculty per student than there were 10 years ago, as the total number of faculty only rose by 7 percent.

We do not know how the numbers of employees in different groups have risen or fallen at Sac State specifically because, as of press time, the school has not responded to the California Public Records Act request that the university made The State Hornet file so that we could access that information.

Nevertheless, the fact that total pay for management personnel rose by double the amount of average pay heavily suggests that there has been growth in the number of management personnel employed here.

As this school year ends, the powers that be in the CSU desperately need to rethink their priorities.

Are this many new administrative positions necessary while asking students to pay more money? Do these administrators deserve higher pay raises than the faculty who work with students day in and day out?

And unless the administrators answer those questions differently than they have been, get ready to write a fatter check to them by this fall.

Steven Aunan • May 17, 2017 at 10:21 pm

Read up on Clark Kerr’s “Multiversity” and you’ll understand WHY “administrative positions rose 221 percent and tuition went from virtually non-existent to $2,272.” For instance:

“One of the major differences between Kerr’s university model and those preceding it was that instead of having one central animating idea, the multiversity had many. A plethora of sometimes conflicting uses led Kerr to claim that ‘the university is so many things to so many people that it must, of necessity, be partially at war with itself’ (Kerr, 1982, p. 8).” (See College Quarterly, Spring 2013, Vol. 16, No. 2.)

Do students want a multiversity that attempts (and fails) to be all things to all stakeholders? If so, then someone must pay for the administrators, support staff, coaches, professors, advisers, graduate assistants, and student workers who demand to be paid adequately for the numerous programs they provide.

And if students (or parents) don’t pay, who does? Would you demand that “taxpayers” or “the rich” foot the bill? Yes, I think you would. Because “free education.”

So imagine that the “multiversity” escaped the fiscal restraints of tuition and limited government funding, and instead was “fully funded.” How long do you think that would last?

And then imagine that the university went back to “one central animating idea” instead of the “plethora” you pay for now.

As a wise man once said, “You can’t always get what you want. But if you try, sometimes, you get what you need.”