Born to be mild

February 12, 2003

If this were 1973, college students across the nation would be pissed off at the United States.

They wouldn’t stand for the government’s threat to send their peers halfway across the globe because Iraq may or may not possess weapons of mass destruction. They would question President Bush’s motives for a regime change in the Middle Eastern nation, both the official – Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein is “evil” – and the more obvious – Hussein is sitting on an oil-rich gold mine any good Texan would salivate for.

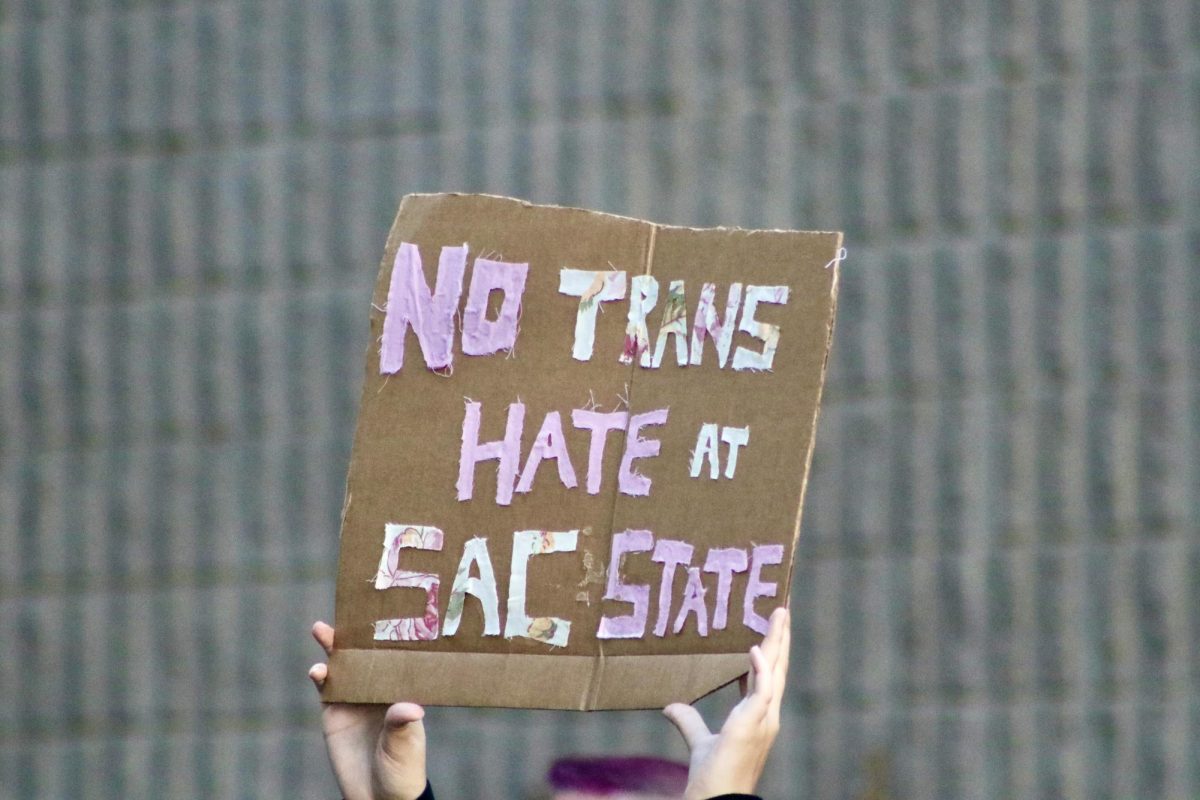

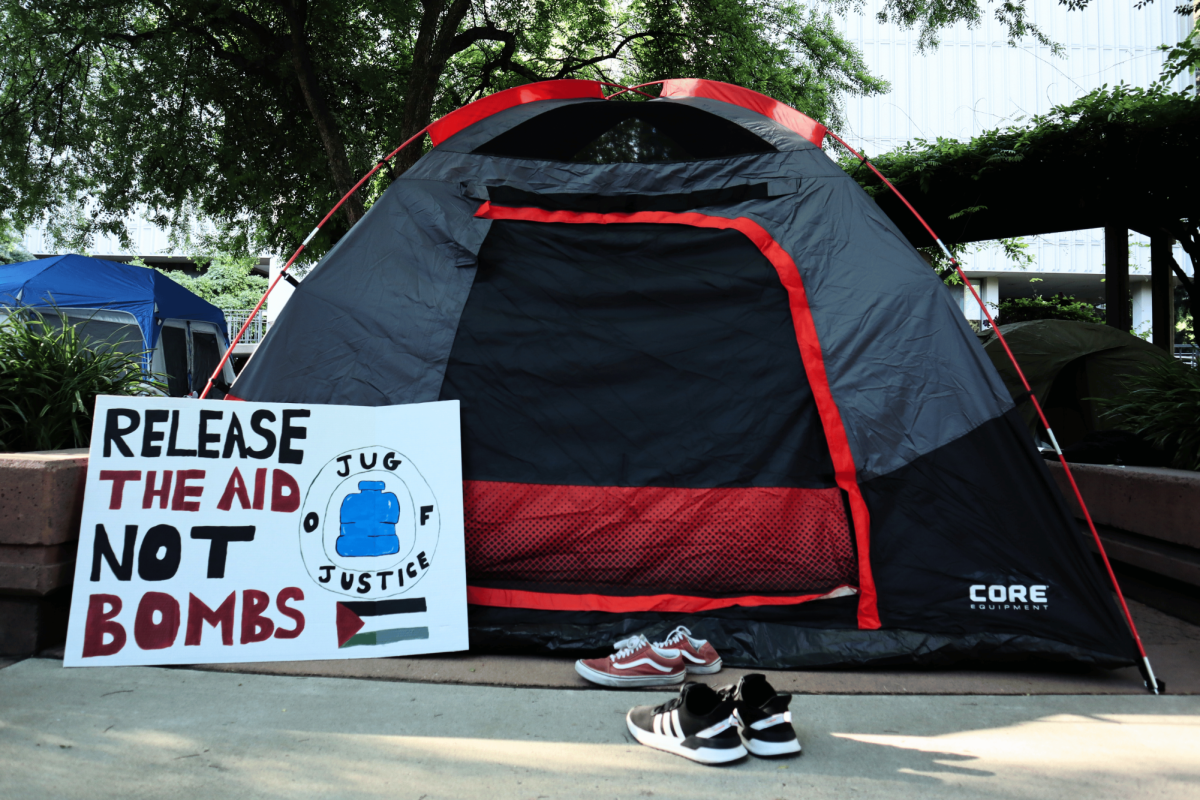

If this were 1973, students would demand answers. Flags would be burned. Petitions would be signed. Administration halls would be occupied.

Hell would be raised.

That is, after all, what students did in the late 1960s and early 1970s after seeing the war in Vietnam for what it was: an unnecessary Cold War mess that ultimately killed nearly 60,000 American soldiers.

Unfortunately, the days of activism on America’s college campuses are long gone. The anti-war songs of Country Joe McDonald, Bob Dylan and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young have been replaced by the skin-deep pop of Christina Aguilera and Britney Spears, the musical equivalents of a Happy Meal. Many students don’t care that the United States will likely ignore the advice of many allies and send troops to Baghdad in the coming weeks, despite a lack of clear, convincing evidence showing that Iraq is hiding weapons from UN inspectors.

All they seem to care about is how long J-Lo and Ben’s marriage will last. Or who the next woman to get the ax on “Joe Millionaire” is. Or whether Simon can come up with a really snappy insult on “American Idol.”

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. In the weeks following the Sept. 11 tragedies, the consensus was that the trivial would no longer matter. People suddenly paid attention to the events of the world. They learned words such as “Taliban” and “Al Qaeda.” Talk about Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman’s breakup was replaced by Osama bin Laden and Afghanistan.

For once, life took precedence over art.

Then, in a blink, it was over. Bin Laden hasn’t been found. The National Guardsmen with the big guns left the airports. People began to feel safe again – and retreated right back into their cocoons.

The only thing that seems to remain from the patriotic fervor that followed Sept. 11 is the blind faith the American public still has in the stars of that real-life drama: Bush, Secretary of State Colin Powell and Attorney General John Ashcroft. For the past one-and-one-half years, the White House could do no wrong, even when it pushed Congress to pass the eerily Orwellian Patriot Act in 2001, giving the FBI the right to violate numerous civil liberties in order to fight terrorism.

Therein lies the problem. Give the kids the keys to the Ferrari, they’re going to take it for a spin. The majority of the American public – including many students on this campus – simply nod their heads in approval when asked whether war with Iraq is necessary. Then comes the rhetoric: Hussein used biological weapons on Iran and the Kurds. Iraq harbors terrorists. Someone, somewhere at sometime claims to have found an empty canister with the word “Smallpox” written on the label.

These are all valid points, to a degree. But is this worthy of an attack and subsequent rebuilding effort that is likely to cost billions of dollars, not to mention human lives? Does Iraq really pose as large a threat as, say, North Korea does? If not, then is oil the real motive for war?

Nobody has the answers to these questions. That does not mean they shouldn’t be asked. Colleges and universities are places of learning and knowledge, where ideas can be shared and theories can be argued. Yet there are no signs of protest on the Sacramento State campus. No marches, no discussions, no hell being raised.

If you’re against sending troops to Iraq, speak up. If you’re 100 percent behind Bush, say so. If you really have no idea what’s going on, learn about it.

Don’t wait for the body bags to start coming home before deciding to raise your voice. If those students from 1973 could teach us one thing, it would be that protests don’t mean much when they come too late.