OPINION: Reform needed to end not-so-secret cheating in NCAA

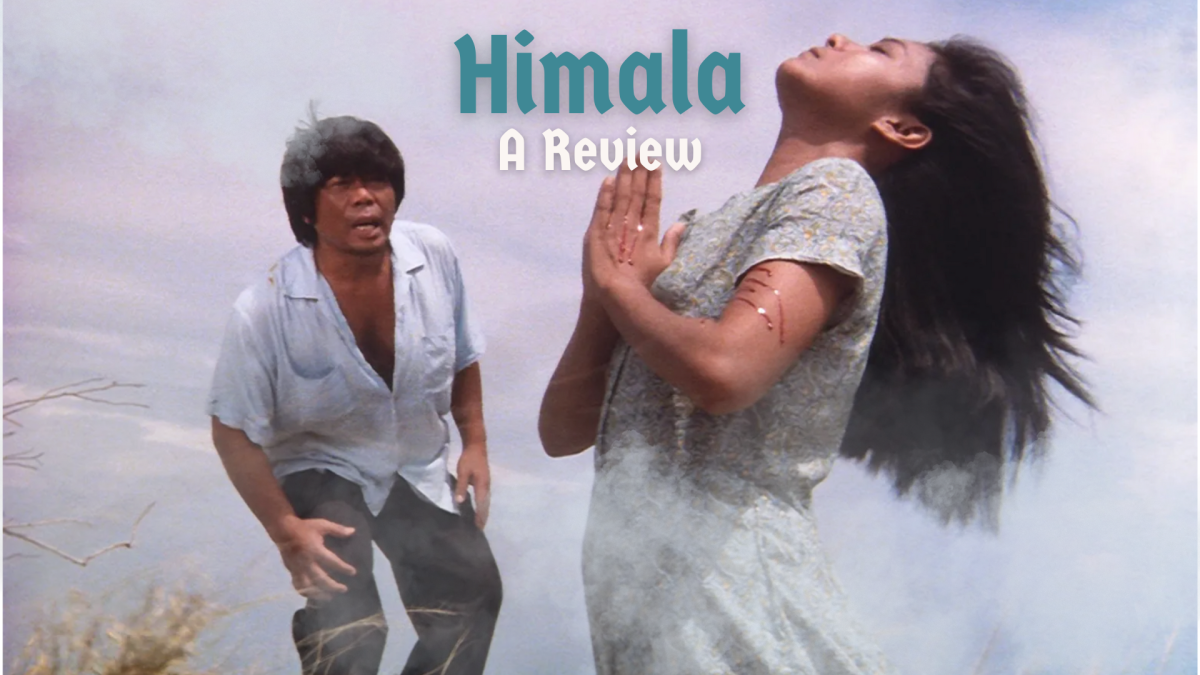

Adam Glanzman / Flickr CC BY 2.0

Louisville point guard Peyton Siva holds up the winning trophy after his team won the Division I NCAA men’s basketball championship in 2013. The title has since been vacated after the program was discovered to have committed multiple recruitment violations.

April 3, 2018

March Madness is over, and it is now time for college sports fans, basketball fans in particular, to prepare for a turbulent offseason.

When games start next fall, we may know a lot more about our favorite ballers and how much they were paid to go to school.

It started when Yahoo! Sports reported that several elite college basketball programs have been linked to giving some top recruits improper financial and other benefits that would affect their amateurism.

Federal agents showed hundreds of documents and intercepted more than 4,000 calls across 330 days monitoring several targets in this case.

The most amount of money that has been reported so far is that Arizona’s head coach Sean Miller discussed bringing in freshman standout player and likely top-3 pick in the upcoming NBA Draft Deandre Ayton for $100,000.

The evidence shows that there is an underground economy for college recruiting. The reporting, briefly superseded by one of the most exciting championship tournaments in recent memory, is likely to continue.

This doesn’t surprise many people, and the NCAA is truly to blame.

College athletics is a billion-dollar business for the NCAA. However, college athletes don’t get paid.

Some athletes can get a full scholarship, but the amount of scholarship funds and other benefits student-athletes get at high-profile institutions sometimes isn’t even close to how much a university can rake in.

According to CBS Sports, in 2017 Alabama’s football program reportedly brought in $108.2 million in revenue, $45.9 million of that in profit. Business Insider reported that the Duke men’s basketball program made $27 million in 2014.

With all of this money being thrown around we seem to forget who is getting short changed in this whole situation: the college athletes.

The only way that the NCAA can make things fair for players is to at least pay the athletes some kind of portion of the profit they bring in.

The collective bargaining agreement between the NBA and its players means players and the league’s owners split revenue down the middle.

Can college players retain their rights to scholarships and receive 25 percent of profits, perhaps?

This might mean that some athletes will be close to millionaires in college, but it’s only a quarter of what they bring to the table and also a small percentage of what their coaches are getting paid.

If a school wants to invest $100,000 in a player to make sure he or she goes to their school, it shouldn’t be illegal: it should be welcomed.

Business Insider also mentioned that if athletes were in a free market like the NBA, the average player at Duke would be worth $1.3 million while Louisville basketball players would be worth $1.5 million.

It’s a business, anyway. The schools that can get the best players win more games, increasing their popularity and therefore making more money in the long run.

But alternatives are on the horizon for prospective college-aged athletes. The NBA is currently trying to legitimize its minor league, The G League, as an option for basketball players coming out of high school, as well as reform its rules on when a player can join the NBA. Ending the current one-and-done cycle of college’s best players might also move the NCAA to change its scholarship system for good.

Another reason why these athletes should be allowed to get paid is that when they are in season, it’s like having a full-time job.

In season, an athlete can be doing sport-related activities up to 40 hours per week.

The NCAA has been milking its athletes for too long.

Until people are actually paid for their time equally and fairly, the underground economy will continue.