EDITORIAL: Women need better representation in Sac State athletics

Only 2 out of 11 women’s teams are coached by women

Alex Daniels – The State Hornet

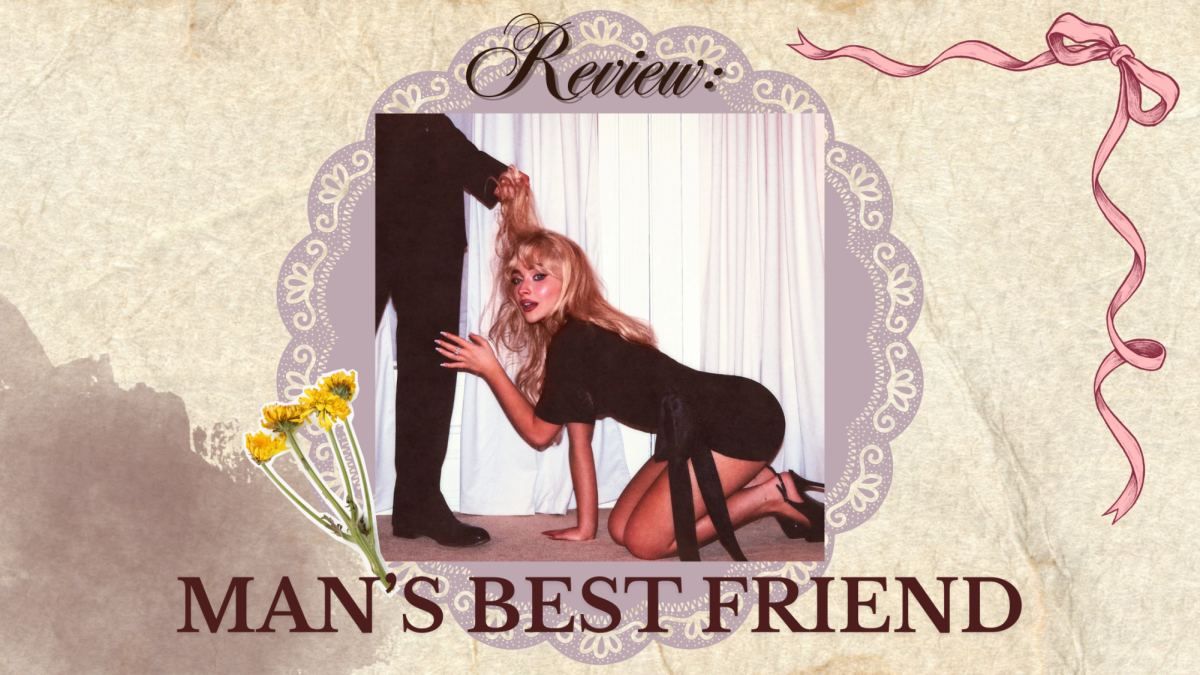

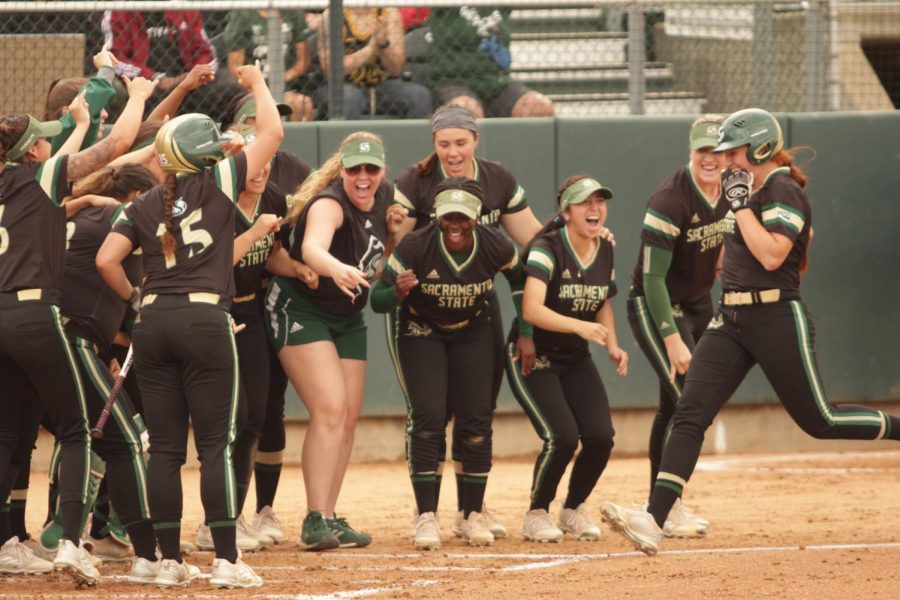

The Sacramento State softball team celebrates with sophomore outfielder Suzy Brookshire, right, after she hit a home run against the University of North Dakota at Shea Stadium on Saturday, April 28, 2018. The Hornets defeated North Dakota 4-1.

March 27, 2019

While women are nearly equally represented with men across administration, faculty and staff according to the 2018 Sacramento State Campus Climate Survey, the same cannot be said for women’s athletics.

Sac State has 19 athletic teams on campus, 11 of which are women’s teams. Of those 11, only two are led by female head coaches.

RELATED: Meet the only two female head coaches at Sac State

Of the 13 public schools in Northern California with that many sports teams, Sac State ranks lowest in the amount of female head coaches present. At the top of the list are University of California, Berkeley and University of California, Davis with nine each, followed by San Jose State and Stanford University, with seven each.

Story continues below graphic.

For far too long, men have coached women’s teams at Sac State without success, and the record speaks for itself.

Bunky Harkleroad has led the women’s basketball team at Sac State since 2013, but has had little tangible success. In the six seasons Harkleroad has been coaching, the team is 77-107.

Under Harkleroad’s leadership, the team hasn’t even come close to touching the NCAA Tournament. A female coach may not guarantee a winning basketball team, but it’s evident that it’s time for change.

In 2016, the gymnastics team named Randy Solorio as its head coach after Kim Hughes retired following a 34-year career. Solorio was his assistant for most of that time.

While Solorio certainly put in his time, the team benefitted from choosing Tanya Ho as its head coach.

Ho started as an assistant coach at Sac State in 2012, and just before the 2017 season, was named head coach at University of Alaska Anchorage’s gymnastics team, a struggling program at the time. In just her second year, the team hit scores they have never seen and Ho was named the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation Coach of the Year — an award Solorio has never won.

Team members who needed help with problems on and off the mat often went to Ho because they said it felt easier to talk to someone closer to their age. The team currently has assistant coaches Melissa Genovese and Nicole Meiller, who are younger than Solorio and have more recently gone through collegiate gymnastics.

According to the rosters on Sac State’s official athletics site, there are 17 assistant coaches on the women’s athletic teams that aren’t volunteer or student coaches. Of those 17 assistant coaches, eight are men and nine are women.

Out of all of the men’s sports, there are 22 total assistant coaches and the only female assistant is Kimberly Graham-Miller, a track and field assistant. The discrepancy is clear — men are much more prevalent as assistant coaches in women’s sports, while women are scarce in men’s sports.

This trend doesn’t just affect Sac State. It is rare to see a woman get a chance as a football coach or a men’s basketball coach, arguably the most popular collegiate sports in the country. When women do get that chance, they are held to a much higher standard than men and receive much more scrutiny.

Currently, Dartmouth is the only school with a full-time female assistant football coach, and they were written about nationally. If Sac State football found success with a female head coach, they would undoubtedly need to build a much bigger press box.

On a national level, inconsistency in pay or attention between men and women’s sports, for both players and coaches, is often associated with the popularity of one versus the other.

At least partially due to the fact that the WNBA doesn’t receive the same viewership as the NBA, players struggle to earn fair pay. The maximum WNBA salary is $113,500 while the minimum NBA salary is $838,464.

Tennis is the only popular professional sport in the U.S. that gives equal salaries across both men and women.

But in college, a place where everyone should be receiving the same opportunity to succeed, we should not act as a reflection of this national and professional trend. We should be allowing not just our players, but our coaches to nurture their skill sets and resumes, allowing them to grow, to the benefit of themselves as well as our university.

This is especially true for female coaches. If a woman head coach’s barriers to professional entry are already higher, shouldn’t Sac State, an institution that touts its inclusivity, give female head coaches a chance?

As a whole, Sac State needs to give female head coaches more of a chance, even if it means just starting with women’s sports. Being a woman involved in any form of athletics — both on a collegiate level or professionally — means overcoming hurdles purely on the basis of gender.

The most common path toward a career or lifestyle is seeing a role model succeed in that same field. Young girls and women will be more inclined to committing themselves to sports if they see themselves consistently reflected in the collegiate sports world.

Ex Rower • Aug 28, 2019 at 12:27 am

I agree with the article. To add, I was a rower for a while on the novice women’s team. The novice coach doesn’t “believe” in warming us up, he always said it was a waste of “his” time. The only thing we did every morning was jog, we didn’t even stretch before getting on the water. Everyone gets injuries from working with this coach, every year the new girls ask him to let them have time to stretch and he complains that we are lazy and cutting into his 2 hour maximum daily training time with us. Total bs, the men’s novice team and both varsity teams all stretch before hitting the water and they have plenty of team mates who don’t get injuries like we all did. The varsity women’s rowing team coach said that they have to just work with the injuries, otherwise there would be no women’s varsity team at all. He screws us over. It’s been a couple years since I quit, I didn’t even see my first race aka I quit early, and my injuries from this ignorant coach still affect me right now. I did over a year of physical therapy for only minor improvement. The injury I got is a constant reminder that YES stretching is important. I wish we had had a more empathetic and intelligent coach…

Janet Piovlov • Apr 12, 2019 at 11:35 pm

The majority of the facts in this article are false and unsupported by actual evidence. Next time, include your full name since we are required to and provide the sources you claim to have gotten this information from.

Think things through please • Apr 5, 2019 at 1:37 pm

So, if I’m reading this right, you are suggesting that Sac State violate state law, and federal law by basing hiring decisions on the gender of the applicant, rather than their achievements. Maybe you could spend just a few minutes doing a bit of research on personnel law before writing such and article.

Informed gymnast • Apr 3, 2019 at 4:15 pm

The facts about the Sac State gymnastics staff are inaccurate in this article. Coach Tanya Ho did not coach Alaska until the 2018 season. She just completed her second season at Alaska. She was first assistant for two seasons with Sac State. I agree with women representation, the discrepancy has gone on too long, but don’t throw people under the bus with inaccurate information and facts.

Basketball Fan 2 • Apr 1, 2019 at 9:16 pm

Pkease help me understand what sex,race or creed has to do with making you a better basketball coach. Just because you are a man or a woman does not justify an opportunity. You earn your way in this world by the sweat of your brow. Coach Harkelroad has 19 years experience 325 wins, has a 1st class coaching pedigree. Comes from the state of kentucky where Basketball is King. Sac State is very lucky to have such an dedicated and innovative coach. Finishing 2nd in the nation 3 years ago behind U Conn in scoring average is no small feat. Coaches shouldnt be hired off of quotas for race or sex. Judge the man or woman based on their credentials.

Basketball fan • Mar 27, 2019 at 6:25 pm

Coach Harkleroad has had more success than any other Division 1 women’s basketball coach in program history. He has more wins in a shorter amount of time. His teams have lead the NCAA in statistical categories. He took a team to the WNIT third round, which was the first time any Division 1 women’s basketball team at Sac St has made any type of postseason besides conference tournaments. These are tangible successes. If you followed the team more closely you would know the team sustained major injuries the last two seasons. In addition, they had one senior on this years squad which means the program is rebuilding. Lastly, the Hornets Nest, while it has its nostalgia and intimate setting, is a challenging facility to recruit legit Division 1 players to .