Archaeological curation facility working with Native tribes to recover remains

‘Our ancestors have been waiting for a long time.’

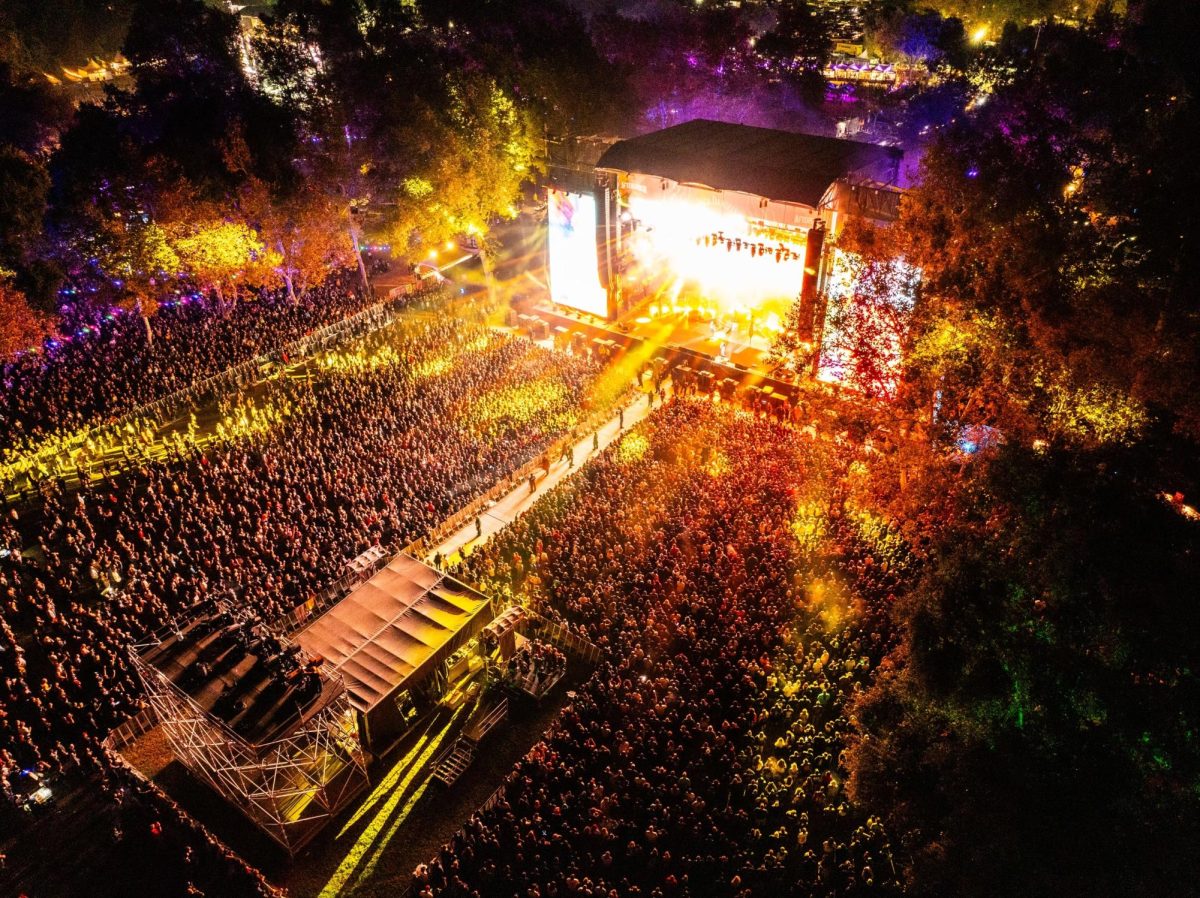

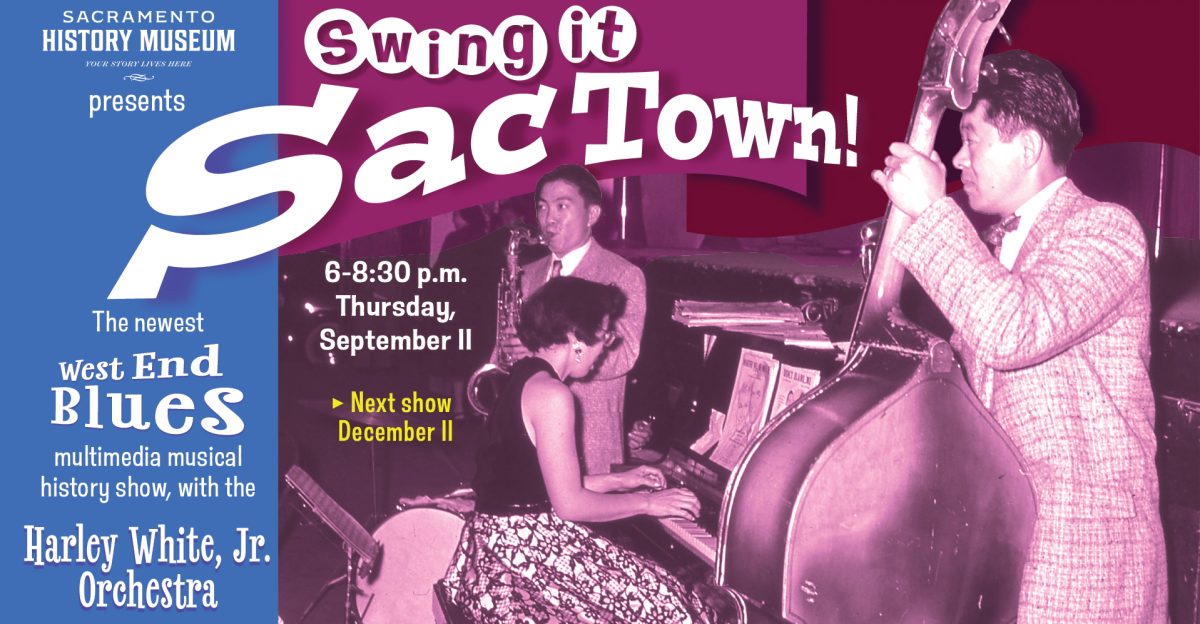

Ethnic Studies Professor Anthony Burris outside of Tahoe Hall Oct. 19. Burris, a member of the Ione Band of Miwok, worked with the university as a representative of his tribe in repatriating items, prior to teaching at Sac State.

November 21, 2022

Sacramento State’s archeological curation facility houses a collection of artifacts and fossils from Northern California. Among their collection are human remains from various Native American tribes throughout the region. For the last decade, Sac State has been working on returning the remains.

The return of cultural items and remains has been an issue faced by Native Americans across the country for decades with attempts often hampered by bureaucracy. Recent changes in state legislation has made this process a bit easier for California Indian tribes to regain possession of these items.

In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was enacted by the federal government, requiring federally funded institutions to work with indigenous groups to return culturally affiliated items and remains. In 2001, California enacted CalNAGPRA to cover holes in federal law, applying it to state funded institutions as well.

The bulk of Sac State’s collection is made up of items from the Ione Band, Shingle Springs Band, the United Auburn Indian Community, Wilton Rancheria, Jackson Rancheria and Buena Vista Rancheria. These items included funerary and sacred objects and human remains.

At Sac State, compliance is handled by the school’s NAGPRA coordinator Sara Eckhardt and the ACF Director and anthropology Professor Jacob Fisher. Eckhardt and Fisher took up their positions in August 2019 and August 2010, respectively.

“I had an interest [in repatriation] going all the way back to undergrad,” Fisher said. “Our perspective of who owns the past has shifted so Indigenous peoples have a voice in what their actual past is.”

Eckhardt had worked for the Tennessee Division of Archeology in Nashville, Tennessee for before coming to Sac State and her work there got her interested in being involved with NAGPRA related projects.

Fisher said his job is to be a liaison between administration and NAGPRA staff and provide oversight for NAGPRA related procedures, such as tribal consultation and documentation.

Eckhardt said the collections at Sac State consist of multiple sites which in turn consist of multiple items. There are roughly 350 collections currently under the university’s control. Fisher said there were also several collections from other institutions at the ACF that the university did not have any control of.

Institutions submit a preliminary inventory and summary of their collection to the NAHC, which is then placed on their website for tribes to review, Eckhardt said. The inventory lists are then sent to tribes for more review and after claims are submitted and notices are published repatriation can start.

“That’s the clean version,” Eckhardt said of the lengthy claim process. “It can be way more complicated.”

One tribe to go through the repatriation is the Ione Band of the Miwok, a federally recognized tribe. Assistant Ethnic Studies Professor Anthony Burris is a member of the band and has served as the chairperson of their Cultural Committee from 2012 – 2018.

“I’ve kind of had a lifelong involvement with this issue in general,” Burris said. “Both my father and my grandfather worked on this issue, so I’ve been around this topic since I was a kid.”

Burris said while he was on the committee they had worked closely with Sac State with consultation on ancestor repatriation for the last decade.

Recent legislation in the form of Assembly Bill 275 has also made it possible for non-federally recognized tribes to make use of CalNAGPRA.

AB 275 was signed by the governor on Sep. 25, 2020. It created the requirements for preliminary submissions and consultation mentioned earlier and revised the definition of “California Indian tribe,” to include not just federally recognized tribes but non-recognized tribes who are on a list kept by the NAHC.

The Konkow Valley Band of Maidu, originally known as the Kojomk’awi are one of such non-federally recognized tribes in California. Matthew Gramps-Williford is a member of the tribe and serves as their vice-chair, cultural resource director and NAGPRA coordinator, the latter of which he said he took charge of the same day AB 275 was signed.

“Previously there was a NAGPRA representative, who had been with the tribe for ten years and worked to get stuff repatriated,” Gramps-Willford said. “But that was pre-AB 275, and there was always the issue of us being a non-federally recognized tribe.”

Gramps-Williford said the Konkow Valley Band will be one of the first non-federally recognized tribes to use CalNAGPRA and AB 275 to repatriate items claiming ceremonial baskets from UC Berkeley. While the bill has given the tribe a seat at the table, Gramps said, it hasn’t necessarily made things easier for the tribe.

“I was informed from the institute we were working with for those two baskets that it should have been a quick and easy process,” Gramps-Williford said. “I even went in front of that institution’s tribal advisory committee, gave them a narrative to prove cultural affiliation, and had other local, federally recognized tribes say the baskets were out of their area. In saying that, we have still not received those baskets.”

Gramps-Williford said other non-federally recognized tribes would go through neighboring federally recognized tribes to get the items, having them claim them on their behalf.

“I’m glad for them and everything, but it kind of also takes away from the identity of the non-federally recognized tribe when the federal tribe is giving them something,” Gramps-Willfiord said. “I don’t know, to me, it looks like they’re handing them something. It’s not like they’re receiving it; it’s their culture.”

Gramps-Williford said the issues they have faced working with CalNAGPRA and AB 275 have primarily come from the NAHC. He said there were other institutions ready to return items, but they were waiting on approval from the NAHC.

“I don’t really understand why they have to okay it,” Gramps-Williford said. “If the institute and the tribe and the state of California has come to an agreement that ‘yeah, these items do belong to this band or this tribe,’ then what’s the problem?”

Gramps-Williford said the NAGPRA team at Sac State had been professional and respectful of his tribe. He said Sac State had reached out to archaeologists who may have collections not turned in and tried to connect them to the Konkow Valley Maidu.

Gramps-Williford said there were some complications in trying to repatriate remains, saying he was told they could only be repatriated under federal NAGPRA. He was adamant that CalNAGPRA’s guidelines should include human remains.

“Sac State’s mind is in the right place, but like everything else they have to follow guidelines and laws,” Gramps Williford said. “The only way we could claim these ancestors would be to have a federal tribe come in, claim and then give to us and we will not do that.”

Another important aspect of AB 275 is the greater weight it puts on tribal traditional knowledge when it comes to determining cultural affiliation. AB 275 specifies tribal knowledge as being expert opinion.

“In the past, museum folks, anthropologists, archaeologists, osteologists, whoever, have been considered the experts,” Burris said. “AB 275 changes that dynamic. Now it’s tribal expertise that’s deferred to and I think, from a tribal perspective considering these are ancestors, these are tribal materials. Of course we are the experts.”

Eckhardt and Fisher said the legislation was still so recent that it was hard to give a definitive answer on how effective it will be in the long term. Gramps-Willford said he hopes the rules and regulations of CalNAGPRA are sorted out quickly.

“We just need the guidelines to get put in place and implemented as quickly as possible, because our ancestors have been waiting a long time,” Gramps-Williford said. “Once they get home they can sleep, they can be in their traditional homeland and meet with the other ancestors. That’s what we need.”