As conversations surrounding health care and its accessibility for all Americans are growing, a conversation that fails to follow it up is the growing disconnect between healthcare workers and their non-English speaking patients.

Sacramento State currently has a foreign language exemption for public health, nursing and health science majors in order to help these students obtain their degrees and finish in four years. These majors are designed to educate people on the ways they can take care of their future patients, yet they are leaving out a whole demographic of patients who don’t know English.

According to the 2022 U.S. census conducted in Sacramento, Latinos are the second largest group at 28.9%, while white people make up about 40% of the population. The numbers are only going to continue to rise as the Census Bureau found that the Mexican population was the largest Hispanic group in 90% of U.S. counties since 2020.

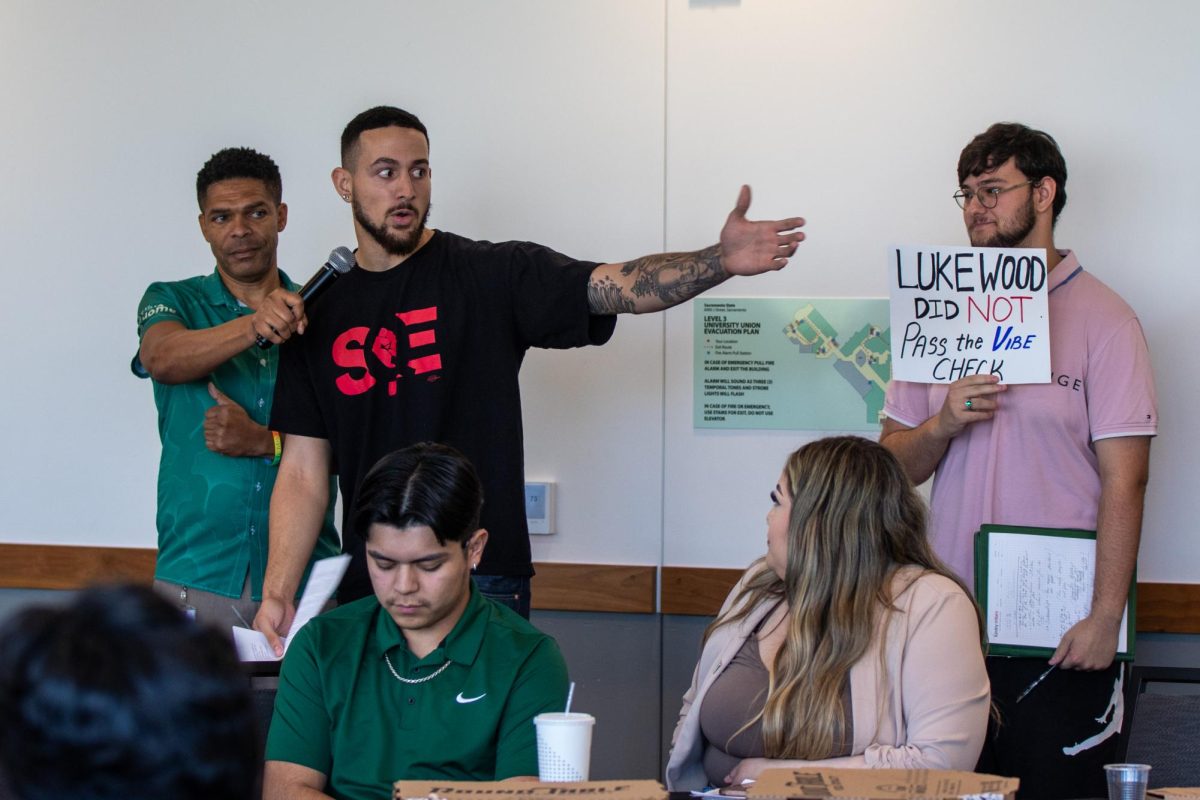

Sac State can say that these exemptions are because they need to make room for students to finish on time, but why does a class that exposes you to the people and cultures you’ll interact with have to be seen as not needed?

In February 2021, after my grandmother was diagnosed with stage four liver cancer, I volunteered to help my mom by taking care of my grandma on the days I had school since we were still online. I stayed with my grandmother at her house about four days a week and watched as nurses would come by to check her levels and ask about how she was reacting to the chemo.

Unfortunately, many of these nurses did not speak Spanish and since my grandmother spoke minimal English, I was put in the position to bridge the gap with my own entry-level Spanish that did not include medical terminology.

Oftentimes, my grandmother would tell the nurses she was fine because she knew how to say that in English and didn’t feel like trying to elaborate. The only time they got told the whole truth was when my mom or other family members were there to help my grandmother translate that she was actually in a lot of pain or had been feeling dizzy the day before.

The gaps in patient care communication with non-English speakers have gone back decades in research as more people have come forward with their own stories about the horrors of feeling so isolated from the people around them who couldn’t communicate what was going on.

In 1970, USC Medical Center workers in Los Angeles were exposed for their abuse of Mexican women whom they coerced into sterilization. Their method was to repeatedly approach these women while they were in labor and force them to sign consent forms written completely in English with no translation so they were unable to ask questions.

A 2015 documentary “No Más Bebés” detailed a group of immigrant mothers who had sued Los Angeles County doctors, along with the U.S. government, stating they were deceived into sterilization and hysterectomies after giving birth during the late 1960s and 70s.

I, myself, had undergone numerous life-saving operations as a child. I cannot even begin to imagine how much harder those experiences would have been had my parents not been able to communicate with the nurses and doctors that came in and out of my room.

However, I am one of the lucky ones. I’ve shared rooms with children who did not know as much as me and listened to the doctors throwing words at them to see what they could comprehend before leaving to get a nurse who would explain why they were being prodded with needles.

While it would be ignorant to assume that every nurse who takes a beginning-level Spanish course would have the ability to communicate perfectly with their patients, the insistence that being able to learn another language in healthcare is a bonus rather than a basic necessity is setting the future of healthcare up for a decrease of efficient care for minorities.

I felt bad for my grandmother having to rely on translation when it came to something so important such as the progression of her cancer. She watched us get told the news that she would be put on hospice care and collect ourselves quickly so that my mom could relay the news to her.

One of the biggest ways this miscommunication has affected the Latin community is mothers who reported discrimination during the course of their pregnancy and while in labor. Women from all over California have reported feelings of inadequate care and a lack of guidance for medical intervention that could have greatly helped them in recovery.

In instances such as labor and delivery, being able to effectively communicate with your patient can literally be the difference between life or death. Since 2018, there has been a steady increase in maternal mortality rates for Hispanic women, with them jumping from 11.8% to 18.2% from 2019 to 2021.

There are women who have never had to deal with a language barrier and are already at risk for post-childbirth complications. Now, these new mothers are having to advocate for themselves at the mercy of an on-call translator.

I hope that moving forward, Sac State can see the value in requiring students to take a foreign language course to set them up for successful careers. At the very least, knowing the emotions of your patients can help you understand how they’re doing.

It’s important to see more healthcare workers who look like us, but I don’t believe it is too much to ask that there are workers who can communicate with us as well.