Editor’s Note: The usage of Hispanic, Latino/a/e/x and Chicano/a/e/x is in accordance with the preference and language of the sources and/or organizations included in this story.

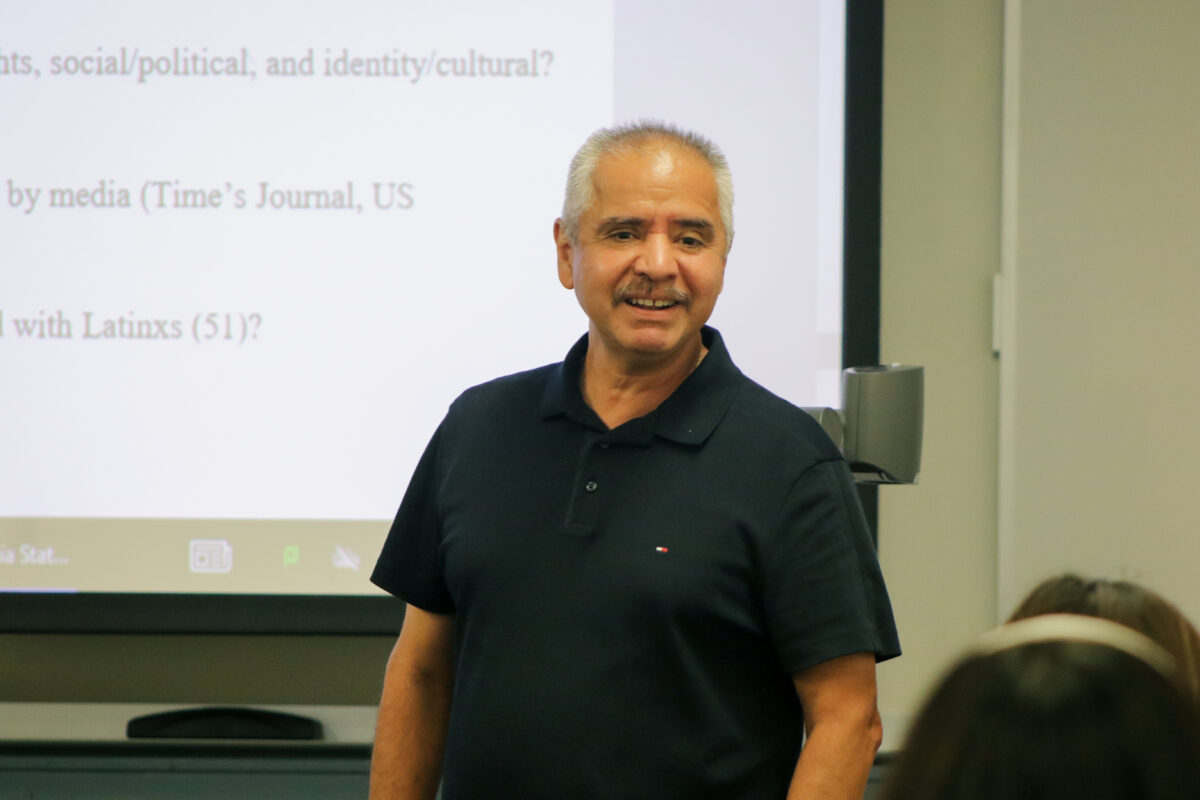

As a fourth generation farm worker, Manuel Barajas’ journey to the U.S. was not unfamiliar, but the career he made for himself in the face of adversity is a powerful achievement.

The youngest of four, Barajas recalls his early years in Michoacán, Mexico, where he and his siblings were often left in the care of close neighbors while his parents traveled to the U.S. to work in the fields.

When his family finally made the decision to settle down in Stockton, California, Barajas said he still felt as if he was back home in his village. The city was a hub for migrants who came to the same place for work.

As a migrant child who worked in the farms, the school environment was not welcoming to immigrants like him. Most students came from a similar background, but were taught by all-white educators.

“The curriculum didn’t reflect our histories, culture or languages,” Barajas said.

As a young student in the 1970s, Barajas said he experienced the segregation of classrooms; only becoming fully integrated when he was in the third grade.

“It felt very hostile,” Barajas said. “We were being integrated busing and the schools were very nice, very manicured lawns and playgrounds. The teachers were not used to seeing us, like ‘ghetto kids’.”

Additionally, Barajas said that teachers discouraged him from speaking Spanish. He said these hostile experiences would serve as a catalyst for the change he hoped to make in a classroom of his own.

During his undergrad years at UC Davis, he discovered the subject of sociology, a social science that focused on the inequalities of society. This made him reflect on his experiences with segregation, labor exploitation of fieldworkers and nativism.

As Barajas advanced his educational career with a master’s degree and subsequent Ph.D. in sociology from UC Riverside, he said the gap in representation between Chicanx students and faculty in the U.S. became more apparent to him.

“For every ten white students, there is one white professor; yet for Chicanx, there are about 200 students for a single professor,” Barajas said.

When he came to Sac State, Barajas said he saw the same cycle of large cultural disparities between faculty and students taking a toll on students who didn’t feel connected to their professors.

“After the Great Recession, faculty of color were diminished to almost nothing, especially brown and Black folks,” he said. “We were reduced overall by a quarter, but Black folks got reduced by more than 45% and brown folks/Chicanx reduced by 60%.”

That is when he made the decision to work in collaboration with other educators to create the Center on Race, Immigration and Social Justice. He said the center is dedicated to producing critical knowledge for students and faculty that properly reflects communities, and their concerns and interests.

Heidy Sarabia, a research coordinator for the center, met Barajas back in 2013. Sarabia worked with Barajas for many years helping to mentor and provide spaces for Latinx students to be heard on campus.

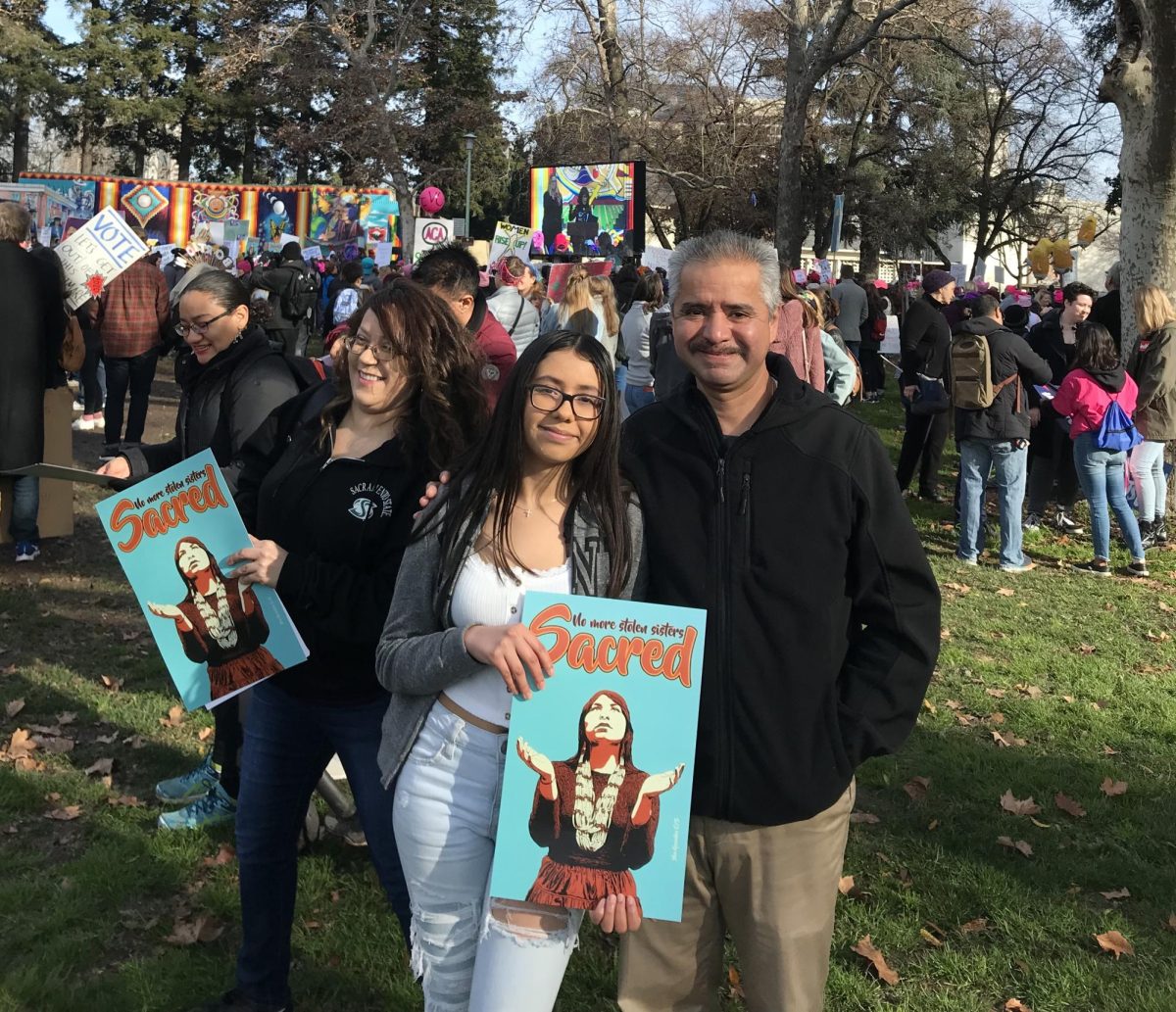

“The history of the center is our engagement and our reactions to what is happening and bringing the conversation, but also thinking about solutions by inviting community members and artists to help us think about ways to move beyond the pain and into making changes,” Sarabia said.

Sarabia said she is most proud of their work together on the ‘Forced Separation of Loved Ones: State Violence, Terror & Trauma’ event in 2018. The CRISJ event hosted a panel of speakers to educate the community about the detention centers that families were being placed in and the separations of families of color in society.

The students from his mentorship program recount the feeling of finally having a professor who made space for students from different cultural backgrounds and encouraged them to build life goals out of past struggles.

Sac State sociology graduate Rebecca Romo was Barajas’ first mentee in 2004. She said his mentorship had a huge impact on her professional career.

Romo said seeing someone from a similar background, as an immigrant and a first generation student, gave her the motivation to continue pursuing higher education.

“He just set a great example of a person who had been through adversity and persevered,” she said. “It was really inspirational and I admired that.”

Romo said his support of students who wanted to further their education made her and other students in the classroom feel very comfortable and fostered a sense of belonging.

Patsy Jimenez was another one of Barajas’ mentees who worked with him during her time as a sociology undergraduate in 2014 and during her master’s degree program in 2018.

Barajas made a huge effort to create an inclusive environment by always encouraging his students to speak out on social justice issues going on in the community, Jimenez said. Additionally, Barajas wove activities into the curriculum for students to talk about their own experiences in adversity so they could learn from each other and have a voice in the classroom.

“He provided for us a transformative educational experience, for us to feel more empowered, feel more confident, to be more informed and respond to issues that were happening around our communities,” Jimenez said.

Barajas said his work with students is about building upon a culture that embraces giving and treating people with the equality and respect they deserve.

Barajas said he thanks his parents for everything he has accomplished. He attributes his inspiration for educating others on the history of inequality and exploitation to his parents. He watched them get up every morning in spite of these hardships and never give up.

“My mom said life is tough, but, you know, remain engaged,” he said.” Don’t lose hope. Be affirming, be positive. Build community. We can make a difference.”

Mario Galván • Oct 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm

I have known Manuel for many years through work with the Zapatista movement and other social issues. I have also participated with CRISJ, and admire the work they have done to bring the community and the academy together.

This article is a well-deserved tribute to Manuel, but also to the many other youth from immigrant families who have risen above the cultural and political barriers in this country to succeed. Like Manuel, many not only succeed on a personal level, but use their own success to help others do so as well.

Congratulations Manuel! And thanks to the Hornet for your recognition of his accomplishments.