‘He thought that journalism was a sacred calling’: Remembering late Sacramento State professor

Former students, family celebrate life of Bill Dorman

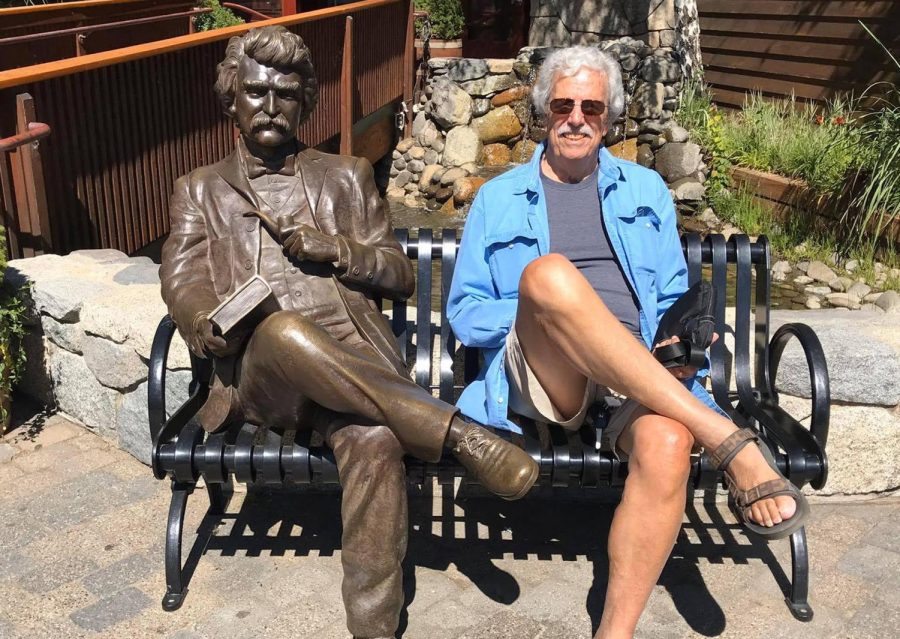

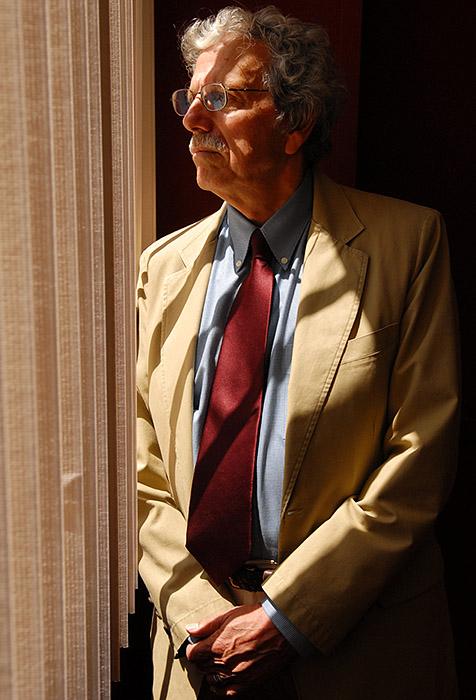

(L-R) Pat and Bill Dorman, June 1990. The two met as students at Sacramento State in the early 60s. (Photo courtesy, Jan Haag)

May 16, 2022

With a career as a journalism and government instructor at Sacramento State that spanned over four decades, Bill Dorman’s impact on students and the university reverberates across demographics.

When news of Dorman’s death reached social media, accolades and anecdotes burst forth on Twitter, Facebook and in the comments section of a GoFundMe organized by his son and daughter Chris and Kym Dorman and his wife Pat.

According to Chris, the funds collected through GoFundMe will create a scholarship in his father’s name at Sac State and support the Friends of the CSUS Library, for which Dorman was the board president.

Raised in the 50s by a single mother who helped define his view of the world, Dorman was apparently cynical about high school. In an interview with Rhea Stone when he retired, Dorman admitted that he was bored with school at a young age and didn’t do well until he began pursuing higher education.

As a college student, Dorman said he developed a passion for both government and journalism but through his connections with students he helped to shape a field of inspired journalists who took their newly activated and honed skills into the world and, in many cases, still practice those skills today.

Bill Dorman’s time at Sac State began long before entering the classroom as a professor. It was there that he and his wife Pat met when they were both students.

Chris said he remembers his father as a consistent presence of support and encouragement. A track-and-field athlete and basketball player from as young as six years old, he said his father was there at nearly every one of his events, cheering him on.

“He was just really involved in our lives in many ways and it just really felt lucky to have a father who was that present,” Chris said.

Chris said that he never picked up the knack for becoming a writer as a profession despite his father’s career. However, both Chris and his sister Kym said they learned to analyze the global and personal implications of any issue they approached from their father.

“[He taught us that] we should be trying to affect those geopolitical issues on a scale to have an effect for everybody,” Chris said. “He was committed to appreciating the humanity in every person. I think he tried to imbue that quality into all of his students, regardless of their political persuasion.”

When the Dorman home was built in 1975, its construction was a family affair, meaning not only were there four Dormans involved, but also Pat’s father, Ted Finger. Chris said he looks back at that time as the genesis of his passion for architecture.

“My father was a specialist at being a gopher,” Chris said. “It was perfect for him; he would go to work during the day, then he would go run errands for a couple hours with my grandfather.”

In 1979, Dorman asked Joe Gibson, the president of ASI, to write a letter on behalf of a fellow professor. According to Gibson, Iranian government professor Monsour Farhang’s position at Sac State was endangered because he was the science attaché to the Iranian embassy during the Iranian Revolution while on leave from the university.

Farhang soon went on to teach political science at Princeton. At the time, Gibson said he and Dorman suspected that their efforts would fall short of their goal of saving Farhang’s position at the university, but they agreed that Farhang was a good professor with an important point of view, so Gibson submitted the letter to then-president of Sac State, Don Gerth.

“When that letter got out, I had to wear a bulletproof vest,” Gibson said. “Bill and I have the same philosophy: ‘you don’t do things because you’re going to win; you do things because it’s the right thing to do.’”

Gibson said Dorman rarely minced words in conversation. “He just called it like he saw it,” Gibson said, adding that Dorman’s philosophy on life was extraordinary, which is why people were so drawn to him.

“When college professors go through the tenure process, they are very careful early on, but I don’t know that Bill was ever like that,” Gibson said. “He just exuded intelligence, but also grace. He could tell you how he thought about you and he did it in such a way that was disarming.”

Advisor for The Current — American River College’s student-run news site — Rachel Leibrock said that Dorman had the same drive she does to coach beginner journalists to realize their potential. Leibrock was the recipient of such guidance herself when she stepped into his classroom in the fall of 1992.

“I didn’t really understand how powerful a tool your voice can be as a writer until I took Dorman’s literary journalism class,” Leibrock said.

With Dorman’s help, Leibrock developed a feature story for her final in literary journalism that had her following a topless dancer in and out of her workplace — a story later published as a cover story for Sacramento News & Review while Leibrock was an intern there. She said that position came as a result of Dorman’s recommendation.

“As I was seeing all the tributes to him online, I had this realization that I owe so much of my career to him,” Leibrock said.

As a child attending Robert H. Down Elementary in Pacific Grove, Dorman and two friends developed a puppet show called “Madcap Puppets.” Leibrock remembered a moment when, after hearing news of the death of one of those childhood friends, Dorman shared a tender anecdote about the performances before that day’s lecture.

“Bill Dorman was just this really righteous dude and we got to share this little story with him in this moment,” Leibrock said.

Ellen Junn, president of Stanislaus University said she knew the Dormans through work she did with Pat Dorman since the two have been long-time advocates for early childhood education. Pat developed a newsletter called “On the Capitol Doorstep” which reported legislation involving that subject matter.

Junn recalled planning events held at the Dorman home that sometimes saw an additional 25 people — mostly women — there to hash out plans of attack on legislation. She remembered nights in the full house as activists all settled into their sleeping bags, stretched in rooms throughout the house.

Though Junn said Dorman would sometimes stay for a portion of the often days-long sessions, the group would scare him off.

“He would [often] say, ‘I’m off to go fishing,’” Junn said. “Bill would be there because he’s the long-suffering husband. Their dual careers overlapped in some fundamental ways, but they had tremendous respect for each other’s work.”

Junn said she was impressed with the design of the Dorman home. She acknowledged that not only was the physical structure of their house remarkable but that Pat and Bill Dorman maintained their family connection, which she said was admirable considering their busy lives.

“He had enormous products — his books, writings, mentoring of students, creation of new degree courses — just in his service to the campus,” Junn said. “To be able to have that work-life balance is extraordinary. Their house was much more open and reflected their interest in keeping the family life together as a group.”

As a former editor in chief of The State Hornet and a retired journalism instructor, Jan Haag, like many others, said she credits Dorman for her career not only as a journalist but as an educator. It was Dorman who plucked Jan out for a job teaching as department chair of journalism.

“Bill Dorman, when he believed in you, was your enthusiastic champion forever,” Haag said in a Facebook post after Dorman’s death.

Haag said she had doubts that Dorman’s faith in her was accurate. A couple of weeks after she mentioned her desire to teach in front of Dorman, he reached out with an opportunity.

“He thought that journalism was a sacred calling. One of his great gifts was in recognizing talents in others that many of us didn’t know we had,” Haag said.

Barbara Bevan • Jun 1, 2022 at 12:03 pm

I only knew Bill Dorman casually since I was a friend of his wife Pat. We were sorority sisters at CSUS and had several reunions at Pat and Bill’s lovely home. My husband is from Iran and learned that Bill had written about Iran. We were so impressed with Bill’s intelligence. My only regret is that I did not get to know him very well. The State Hornet article about Bill was very thorough and touching.