Sacramento community shares experiences with homelessness, ways to help

Kizzie Anderson, a Sacramento resident, shares her experience being homeless on Wednesday, March 3, 2021. Anderson said she struggled to find housing because of her credit and issues with the law.

March 15, 2021

“Society does not want to deal with us,” Kizzie Anderson, a formerly homeless Sacramento resident, said.

At least 12% of students at Sacramento State are currently facing housing insecurity, according to Jessica Thomas, Sacramento State’s Crisis Assistance and Resource Education Support (CARES) office manager. At last count in Sacramento, more than 5,000 people were homeless last January, according to Sacramento Steps Forward’s point in time count.

The State Hornet spoke to a Sac State graduate student, a mother of three, and a Sac State archaeology student who were all previously homeless, as well as case managers at Sac State’s CARES office and local politicians.

A Sac State graduate student

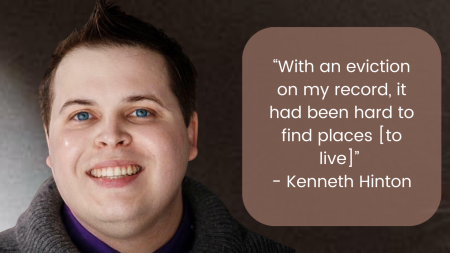

Kenneth Hinton, Sac State graduate student and teaching associate, was homeless last semester and found a place to live only days before the spring semester started.

Hinton said his stepfather was struggling with health issues and underwent surgery, leaving him unable to go back to work and causing the family to be evicted because they were unable to pay rent.

“Because my name was also on the lease, I had an eviction on my record, so that was kind of what I landed in,” Hinton said.

Hinton, 29, said he had to live in and out of hotels at the start of last semester until September 2020, when he got help from the CARES office at Sac State.

Hinton was able to use the university’s emergency housing program, where he stayed from September until Nov. 13, 2020.

“With an eviction on my record, it had been hard to find places [to live],” Hinton said. “I decided to move away from my family and got involved with CARES, which gave me a free month [of housing].”

When Hinton’s emergency housing ran out, he found a place to live through Sacramento Self-Help Housing (SSHH), an organization that provides shared housing for those at risk of becoming homeless to find and retain affordable housing.

Now, in his last semester at Sac State, Hinton said he has a place to live while he finishes his masters degree in English literature.

Hinton said a problem he faces now is not having enough time to study while working enough to afford his own place.

“Towards the end of the semester, you really need to be living every single day reading so that’s why I’m not trying to work that much,” Hinton said.

A Sac State student trying to pay tuition

Ramona Weigel, an archeology major at Sac State, said she was homeless after making the decision to return to school and finding it hard to make ends meet while paying tuition. After negative experiences with roommates, Weigel said she made the decision to move into her van until she could find better accommodations.

Weigel, 43, said that she never felt safe living in her van and worried about sexual assault, robbery and police asking her to move her van from where she was parked.

“I always felt unwanted everywhere,” Weigel said. “I was constantly worried about being arrested or being assaulted.”

Weigel said she typically used resources from the school but was unable to when the COVID-19 pandemic began.

“I was really struggling, I didn’t have a place to study anymore, I couldn’t go to The WELL to take showers,” she said.

Weigel said the relief from moving into emergency housing through the CARES office has taken a great deal of pressure off of her.

“I can get up in the morning, there’s a bathroom, there’s running water,” Weigel said. “I’m safe, I’m not constantly in a state of fear, in survival mode. I have a fridge and a safe place for perishables, so I don’t have to spend a lot of time trying to meet life’s necessities.”

Weigel also said that the CARES office staff cares about their cases in ways no other staff at other institutions have shown her.

Weigel said that her van was stolen while she was living in emergency housing and that CARES paid for her transportation. During a separate incident where she was assaulted, Weigel said she was required to go to court and a CARES worker offered to go with her for support.

“They know my name, I’m not just some number to them,” Weigel said. “They know my dog’s name. I feel like they really care and it’s very individualized to me and what I need.”

Weigel advised her fellow students not to be afraid to ask for help if they find themselves in a similar situation.

“Nobody knew, I didn’t know if I was going to have food that night, or I didn’t know if I was going to have a place to stay, or I really needed a shower,” Weigel said. “I was afraid and embarrassed to ask for help. I didn’t think there was help out there for me. Ask for help if you need it.”

A mother struggling to provide for her children

Kizzie Anderson, a Sacramento resident, also struggled with homelessness after experiencing an abusive relationship and spending time in jail.

“You stay in and out of hotels or in your car before you go homeless,” Anderson said. “I slept in the car with my baby when she was less than a year old.”

While homeless, Anderson said she discovered how many people seem to not care about people who are homeless.

“Society does not want to deal with us,” Anderson said. “ They [homeless people] feel like society doesn’t care about trying to save them.”

Anderson said she got out of jail in early 2019 and obtained housing at a program called Saint John’s because she was unable to get housing elsewhere.

“Even while I was clean, my background still hindered me,” she said. “I got denied because of evictions, being a felon or my credit.”

Saint John’s is a program for homeless women in Sacramento and offers mental health counseling, drug and alcohol abuse counseling and employment counseling. Anderson said she took advantage of the programs that Saint John’s offered in order to better herself.

“I took every class I had to and did not give up,” Anderson said.

Anderson lived at Saint John’s from February 2019 until August 2020, when she was able to move into a home of her own.

Anderson said what would help homeless people is if property managers could only deny a rental application because of debt to a prior landlord or because they do not meet the income requirements, not because of credit issues or criminal history. Anderson said this would have helped her get housing before she went to Saint John’s.

“If we wouldn’t have obtained housing through Saint John’s, I don’t know where we would be,” Anderson said.

How Sac State is helping students affected by homelessness

Jessica Thomas, a CARES office case manager, said that the university provides a number of services to Sac State students experiencing homelessness: ranging from housing to food, as well as support from managers in the office.

Among these services is emergency housing, which is 30-day housing on campus while students work with a case manager to find a more permanent place to live.

Sac State also offers rapid rehousing for students experiencing homelessness, providing them with a place to stay near campus for nine months where they pay $400 to $500 a month, Thomas said. These homes are run by partner agencies like Sacramento Self-Help Housing.

“At the end of lease, [the] student receives a portion of funds paid towards rent back to go towards down payment for [a] new place or other moving expenses,” Thomas said.

Outside of the CARES office, Thomas said that the ASI food pantry provides canned goods and other staple food items like milk and eggs to students in need of food, and that the showers in The WELL are open Monday through Friday for students who need a place to bathe.

RELATED: ‘It’s Sacramento, not you’: Students caught in the crosshairs of statewide housing crisis

Thomas said between twenty and thirty students have already applied to the rapid rehousing program and over six hundred students applied for emergency funds in 2020.

Danielle Muñoz, a case manager for the CARES office, said that the services provided by the CARES office are designed to consider the student’s life as a whole, not just their housing situation, as both her and Thomas come from a mental healthcare background.

“We absolutely have mental health and wellness at the core of these services,” Muñoz said. “In fact, sometimes the way out of homelessness is to address the emotional piece and the trauma that has maybe been a part of their story and why they are homeless, so that’s actually one of the first things that needs to be addressed.”

How Sacramento County is helping

Jeff Harris, who represents District 3 in Sacramento’s city council, said he believes the county needs to provide more services for homeless people suffering from mental illness and addiction, as well as those who are disabled.

Harris said the city used $2 million in CARES Act funds and the county approved over $500,000 in ongoing funding to create a Substance Abuse Respite Center (SURE) detox clinic to help homeless people get closer to getting back on their feet and off the streets.

Harris and newly elected District 3 County Supervisor Rich Desmond have centered their work around the shared concern of providing safety to the homeless and the residents of the communities they reside in.

Because of SURE, Desmond said police have somewhere else to take people besides jail when they are suffering from addiction or mental health problems.

“There were many times where you arrested somebody that was going through an addiction crisis, you had no option but to take them to jail,” Desmond said. “This is great because law enforcement can drop them right off at the SURE center to get help.”

To prevent people from becoming homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency (SHRA), along with the city and county of Sacramento, is providing emergency rent and utilities assistance for renters impacted by COVID-19, according to Katie Valenzuela, who represents District 3 in the Sacramento City Council. The application period is open through March 19, according to SHRA.

“My plan for the next [year’s] budget is to advocate for ongoing emergency funding,” Valenzuela said via Twitter. “We should be helping folks who experience emergencies in the future. Keeping housing should be a priority.”

Desmond said the county is contributing $64 million to SHRA for COVID-19 rent relief program, bringing the fund to over $95 million.

“It’s going to be so great to help people in need,” Desmond said. “Part of the problem with homelessness is preventing people from becoming homeless in the first place.”