‘Pulp Fiction’: A homage to one of the best films of the last 25 years

September 23, 2019

“Pulp Fiction” is one of those movies where every time I watch it, I come out of it with a different interpretation of what the director, Quentin Tarantino, was trying to say.

When I was 10 years old, I snuck out of my room to watch it from underneath the dining room table while my father sat clueless to my presence. As a young kid, I thought of it as a gritty gangster movie set to the backdrop of 1990s Los Angeles. When I was 20, I thought that Tarantino was telling a story of the human condition in which the characters’ actions serve as a reflection (albeit an extreme exaggeration) of moral quandaries people have to deal with on a daily basis.

So when it was recently brought to my attention that Sept. 23 would be the film’s 25th year anniversary, I, of course, had to give it another watch through.

I must have seen this film at least two dozen times, if not more, and each time I have walked away with a different meaning, a different scene to dissect further, a different line of dialogue that I would use to back up my newest hypothesis. This time it only took me about 30 seconds to come to my most recent conclusion: Tarantino just wanted to tell a damn good story.

While the film is littered with small bits of symbolism, both secular and not, the driving force of the narrative is still just the story itself; and while some of those symbolic instances usher the story forward, they are not meant to be interpreted as anything more than a vessel for the continuation of the plot.

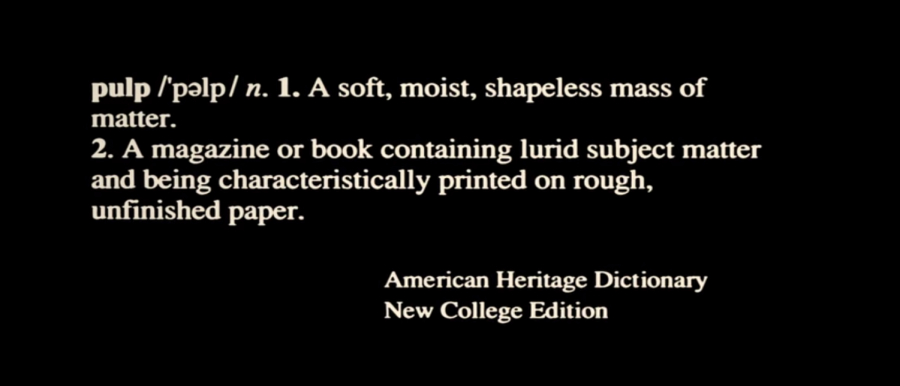

Right off the bat, we’re shown the definition of pulp.

The definition of pulp as seen in the opening of “Pulp Fiction.” The film is celebrating its 25th anniversary.

This definition serves as the only knowledge one needs to know about “Pulp Fiction” before trying to dive deeper into any hidden meanings or symbolism.

In the early 20th century, pulp magazines, or pulp fictions, were sold as ways for audiences to escape to realities that were foreign to them. The magazines told stories of detectives, science-fiction anomalies, damsels in distress, etc. Among the contributors to these stories were authors like Ray Bradbury and H.P. Lovecraft.

As the film’s title suggests, Tarantino strives, and succeeds, in telling multiple of these pulp fictions while incorporating in the first definition of the word ‘pulp’ and forming this shapeless mass of stories into one coherent narrative.

Each story told throughout the film could be a complete movie on its own, but as they merge and intertwine we’re instead presented with something that is the very definition of an end product being greater than the sum of its components.

And while I think that weren’t any intentional hidden meanings or subplots assigned by Tarantino, it’s still fun to explore any fan theories for unresolved plot points.

Probably one of the most divisional of these being one with some of the least amount of screentime: the briefcase.

This film has been out for 25 years and I still have arguments with friends and family anytime we watch it about what was emitting the golden-glow so famously enclosed in this hunk of brown leather. Beliefs range from it being the Oscar Tarantino believed he was going to win for the film, to others thinking it was the diamonds from Tarantino’s first film, “Reservoir Dogs.”

And while I like Samuel L. Jackson’s answer that all that it contained was two lightbulbs and a bunch of batteries, you still can’t convince me that it was not Marcellus Wallace’s soul.

There is, of course, some smaller details that get speculated over, like whether or not the canceled pilot that Mia Wallace starred in, “Fox Force Five,” was a meta-reference to Tarantino’s upcoming movie “Kill Bill.”

But all those aside, what really drives this film home is the exceptional dialogue Tarantino is so well known for.

From Christopher Walken’s speech about hiding Butch’s father’s watch up his ass in Vietnam, to Jackson’s terrifying rendition of Ezekiel 25:17, Tarantino is a master of his craft and it reflects through his writing.

And while there has always been backlash over Tarantino’s more, ahem, colorful language used in his films, there is still a reason why it won Best Writing, Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen and the Palme d’Or upon its debut at the Cannes Film Festival in 1994, and there is a reason that people still talk about it today: it is truly, in every sense of the word, a work of art.