Japanese-American Archival Collection reveals newly-restored swords

Will Coburn – The State Hornet

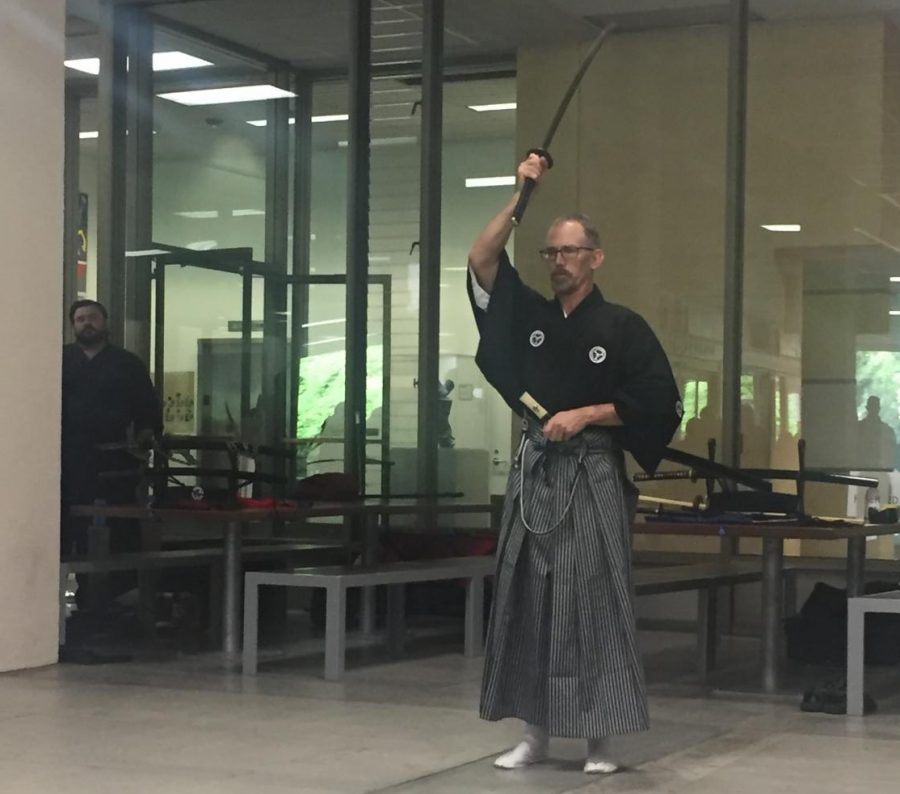

Sacramento State English professor Josh McKinney demonstrates traditional Japanese sword drills during an unveiling ceremony Saturday, April 7, 2018.The swords belong to the Japanese-American Archival Collection’s special collections. The collection includes swords going back as far as 1648.

The University Library Department of Special Collections and University Archives unveiled its newly-restored Japanese sword collection on Saturday.

On display were the oldest blades in the collection, a katana dating back from 1648, a wakashi from 1806 and an inscribed spearhead that had yet to have its engravings translated.

Amy Kautzman, the dean of the University Library, said that the collection will be beneficial for students and will be used “to educate our students about the Japanese-American tradition in Sacramento and the lesson to be learned from (Executive) Order 9066.”

Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, called for the mass internment of American Citizens of Japanese descent.

Restoration of the swords was done by Wayne Shijo and Doug Louie, volunteers from the Sacramento Japanese Sword Club, who did a demonstration of proper care of the swords and discussed their history and cultural significance.

The methods involved traditional sandstone for polishing, a powder to get an even finer finish and a seal of clove oil.

According to Shijo and Louie, sword ownership and rituals became a powerful status symbol in Japan during the relatively peaceful Tokugawa dynasty, which started around 1600 and came to an end in 1860. Many wealthy families fled the strife brewing in Japan by coming to California.

There was also a demonstration of traditional sword drills in the Library’s breezeway by Senkakukan Dojo, as well as tours of the archival collection, the Sokiku Nakatani Tea Garden and the Kensha Garden.

The swords are part of the Japanese-American Archival Collection. They have been a subject of debate in the archives, according to James Fox, the head of the University Library Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

“The archive’s focus is more on internment and the Japanese-American experience post-war, but if we’re going to have these swords we better take care of them,” Fox said. “We have a cultural and ethical responsibility to maintain and take care of them.”

The swords were given to the University Library alongside more traditional archival materials over the years, and the library has amassed a small collection of them.

“The sword club did a condition report four years ago, and offered to restore them then, but that didn’t happen for a variety of reasons,” said Fox.

Story continues below

Shijo said that when they first got to look at them during that condition report, they were in pretty poor shape, and some of them still have major rust damage. Only the blade is cleaned.

The tang, the part of the sword that goes into the handle, is left untouched so that future historians can date the blades off of the wear.

During the restoration process, complex engravings were found on a spearhead. The engraving has not yet been translated.

It is believed the weapon was created as a gift for a temple, and images have been sent to a scholar in Japan to translate the words with proper context.

Fox didn’t see this as only a restoration, but as a conservation.

“Whenever you restore an artifact you change it,” he said.

Fox also said restoration is a last resort, adding that he prefers maintenance.

“By and large, I am not in favor of restoration. I want to keep them as close to the original state as possible,” he said.

This is why the blades didn’t have their handles remade. They were traditionally made with wooden handles, with a layer of manta ray leather, finished with silk, and changed frequently to match the seasons and New Year’s celebrations. Shijo said these fittings often cost more than the sword itself.

The Japanese-American Archival Collection was started by Mary Tsukamoto when she donated a personal collection of letters, diaries and photographs from her time in an internment camp during the second world war. Tsukamoto’s daughter, Marielle Tsukamoto, spoke at the event.

“The original goal was to preserve for the archives documents, diaries (and) photographs for the Japanese immigrant and Japanese-American community, and not only their history but the contributions that they made,” Tsukamoto said. “And most importantly, the story of the forced removal and incarceration of all the Japanese along the west coast, specifically in the Sacramento region.

“So those stories are being preserved as a resource, hopefully as an example of loss of constitutional rights and the need to protect everyone’s rights in the future.”

The Japanese-American Archival Collection has grown to become the largest archive of Japanese internment documents and relics.

The collection also includes clothing, furniture and art created by prisoners during the internment as well as the original temple altar from the Buddhist Church of Florin, which was one of the communities hardest hit by internment.

“We know it’s important to tell the story of what happened to a group of American citizens totally innocent of any crime, any wrongdoing against the government — purely based on race prejudice, hysteria, and failure of political leadership,” Tsukamoto said. “And we’re seeing some of those same dangerous patterns beginning today, which is why it’s so important that students understand what their rights are and that they need to speak up.”

The Japan club is hosting its annual Japan Day this weekend alongside the Festival of Arts’ Sunday Funday starting at 10 a.m. in the library quad.

There will be traditional performances, such as Taiko drumming and the Bon dance, as well as contemporary Japanese dancing and martial arts performances.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Sacramento State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.