The Faces of DACA at Sac State

Profiles of students and a faculty member brought to the U.S. as children

October 5, 2017

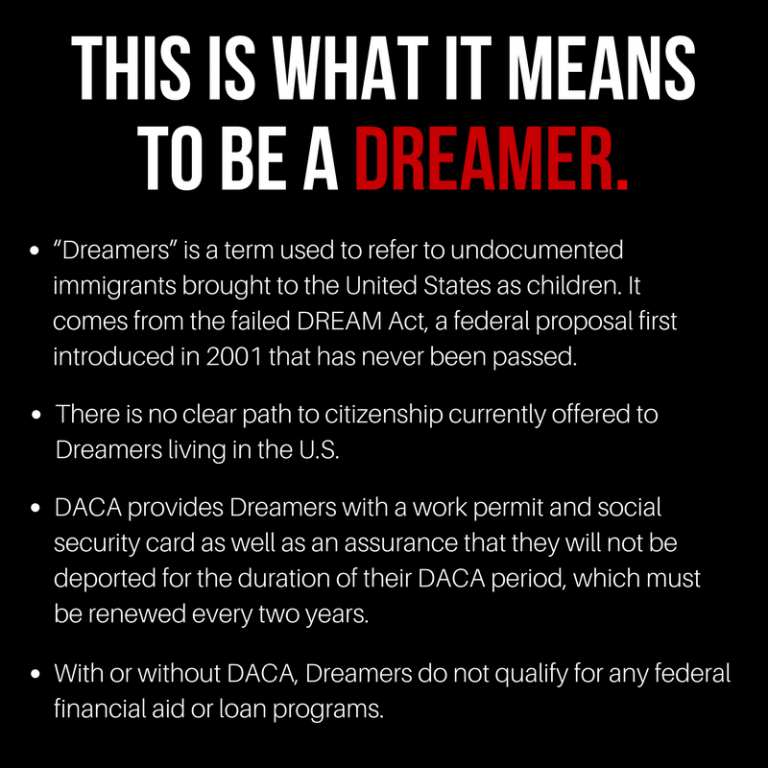

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival, or DACA, has been rescinded and will soon expire; the last extensions are being accepted until tomorrow only. As of last semester, Sacramento State was home to around 1,000 undocumented immigrants, 65 of whom were DACA recipients, according to the university. These are some of their stories.

RELATED: #SacStateSays: Should undocumented residents be given a path to citizenship?

Jesus Limón, brought at age 8

There’s a strong cinematic quality to the chapter of Jesus Limón’s life that begins with crossing the border illegally and ends with getting a Social Security number.

Both began and ended with a car.

Limón remembers vividly driving home with his newly obtained social security card and driver’s license after officially becoming a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival recipient. He realized, slowly and then all at once, that nothing he was doing was against the law.

Limón recalled thinking to himself, “this drive home is the first time I don’t have to fear being deported.”

That fear was established years ago when Limón was snuck into the United States from his birth home in Mexico at just 8 years old.

Taken separately from his mother and sister, Limón had to pretend to have a different name so a woman could use her son’s birth certificate to sneak him across the border. Though the two rehearsed over and over again what to say when someone asked him for his name and birthdate, Limón said he thinks she did not trust him to get the story straight.

“I think as she got closer, she didn’t really trust that I could remember all the details, so she ended up just giving me a pill or something,” Limón said. “I just remember fading out and then just waking back up in an apartment with a bunch of other kids.”

Limón, now an English lecturer at Sacramento State and professor at Sacramento City College, narrowly met the window for DACA requirements in terms of age but is a textbook example of the type of person meant to benefit from the act, as he has spent the majority of his life in the U.S. after being brought here as a child.

(Watch Limón’s video interview below)

Raised in Sacramento, Limón realized that he was different from his other classmates when Proposition 187, which would have prevented him and any other undocumented Californians from using public services including health care and public schooling, passed when he was in middle school.

It was then that a teacher sat Limón and his father down to explain what the law would mean for his immediate future. Although Proposition 187 was ruled unconstitutional and never enacted, it was clear to Limón then that, even in a liberal and Hispanic-heavy state such as California, he would always be on uncertain ground.

“Anything that is maybe insignificant, like riding on the handlebars of another bike, felt like, ‘what if we get stopped because I’m not riding a bike the right way?,’ ” Limón said. “And then the cops take me away and deport me.”

It was this uncertainty, compounded with Limón’s sister dropping out of college, that made Limón decide that if she couldn’t go to college safely, despite a 4.0 grade-point average, neither could he.

“Outside of maintaining a 2.0 to play football, I saw no need to maintain any kind of grades,” Limón said.

Before Limón graduated, California passed Assembly Bill 540, which allowed undocumented students to pay in-state tuition in the CSU, UC and California Community College systems.

Limón attended Sac City with a new sense of hope for his future as a student and citizen and eventually transferred to Sac State. He later graduated with a master’s in English.

What followed was a sort of limbo. Well-educated and highly motivated, Limón felt his options were nevertheless limited. His residency status prevented him from finding steady work, and he scraped by on low-wage jobs and the generous nature of those who had come to know him in his time at Sac State.

Despite the hardships that he faced as an undocumented citizen, Limón said he is appreciative of the unique life he has experienced in the U.S. and it’s cyclical nature.

“The idea of being 17, cleaning the buildings (at Sac State) and then, you know, less than 10 years later being a faculty member in that same building,” Limón said. “That thin slice of life that is the American promise, you know what I mean? That you can go from the janitor’s son to being the faculty.”

Rosa Barrientos, brought at age 4

Rosa Barrientos first realized she was an undocumented citizen during middle school when the director of an after school program recommended her for a scholarship.

The director called her mother saying all she needs to show is her social security number, but her mother said Barrientos didn’t have one.

“In my head, I was thinking, ‘no, I do have one, you just don’t want me to go to college,’ ” Barrientos said.

Barrientos said the constant rejection of scholarships and opportunities to travel outside of her east Los Angeles area frustrated her. She became heavily discouraged after not being able to go on a trip to Washington, D.C. with an extra-curricular group.

“I kept working hard, and I kept wanting to continue working hard, but at a point it was just like, ‘well is it worth all this?’ ” Barrientos said. “Is it worth it, you know, staying up late doing all this homework, working on all these projects? I might not be able to go to college.”

Barrientos describes June 15, 2012 as a special day. While she practiced for her high school graduation ceremony to be held later that day, she received phone calls from family members who were saying “President Obama signed something for undocumented students.”

(Watch Barrientos’ video interview with The State Hornet below)

Barrientos received her DACA approval and a social security card within a few months. Within that same year, she finally got to travel to Washington, D.C. with a United Nations Initiative called Girl Up.

“This is what I was missing out, this is all I wanted,” Barrientos said. “All I wanted was an opportunity, and I got it.”

Barrientos said that the swell of opportunities made her forget that it could all be taken away. When President Trump announced DACA would be rescinded, she remembered that feeling.

“It kind of feels like I was living in a glass house and everything broke, everything shattered,” Barrientos said.

Barrientos said she does not know how to mentally navigate what it would mean for her to be deported back to Mexico.

“Even though I don’t have a lot of family in the United States, it’s friends who have become family,” Barrientos said. “The family I do have (in Mexico), it’s weird because I don’t have that connection with them. They remember me, they know me, but they know a 4-year-old.”

Chris, brought at age 3

Chris, the youngest of our four profile sources, also came to the United States at the youngest age: only 3 years old. He does not remember much of the small town in Jalisco where he was born.

Tipton, California is where most of his memories lie. With a population of around 2,500 in the 2010 census and just barely over a square mile in area, Tipton is what Chris calls his real hometown. It’s where he lived until coming to Sacramento State.

Chris was young and didn’t consider how he got to the U.S. from Mexico until he was in middle school, and an American-born cousin wanted to go visit their family’s hometown. Chris didn’t understand why he couldn’t go.

“My mom looked at me, and I could tell she didn’t want to tell me,” Chris said. “I kept pushing her, and she’s like, ‘if you go, you can’t come back.’ She told me, ‘no tienes papeles,’ which means you don’t have papers.”

The scope of that reality came to Chris during President Trump’s campaign when his mother sat him down and warned him that if Trump won, it would be a problem for all undocumented people.

“When he walked across the stage (Nov. 8), that’s when the fear settled in for me,” Chris said. “I have a little sister who is a U.S. citizen and all that was flashing in my mind was, ‘if we’re gone, who’s going to take care of her?’ ”

(Watch Chris’s video interview below)

Chris first applied for DACA in his sophomore year of high school at the direction of his parents and was awarded his card in his junior year. To that point, he hadn’t realized all of the things he now could obtain that he and other undocumented people couldn’t before.

His DACA card enabled him to work, get a social security number, apply for a bank account, get a driver’s license and apply for credit cards.

“All the benefits that someone with a social security number could get,” Chris remembered his high school counselor telling him.

“That’s when I saw myself saying, ‘I’m definitely going to college,’ ” he said. If my parents can’t afford it, then I can afford it, and I can help them out.’ ”

Editor’s note: Chris requested that we not publish his last name.

Everardo Chavez, brought at age 6

The thought of being sent to Mexico brings Everardo Chavez to tears.

“That’s something I never want to think about,” Chavez said. “Everything I’ve worked for, everything I had, would be thrown in the garbage.”

Chavez said his father was already in the United States working and sending money back to his family before they relocated when he was 6 years old. Despite the young age, Chavez said he always knew where they were going.

“Before I even knew where the United States was,” Chavez said, “I knew that was the place where I was going to have a better life.”

Chavez’s parents did not instruct him on what, or what not, to say about being undocumented because he thinks they did not want him to live in fear.

(Watch Chavez’s video interview below)

It was only when he became older that he began to feel pressured about his residency status because he did not know if he was going to be able to enroll into a university or get any aid without a social security number, despite succeeding in high school as a student and athlete.

Former President Barack Obama issued DACA as an executive order in 2012, giving Chavez the ability to get a social security card and a feeling of belonging.

“I felt like I wasn’t just a ghost, someone who was there,” Chavez said. “I was becoming a part of society.”

President Donald Trump announced in September that he will rescind DACA and wants Congress to write legislation that will serve as the replacement. President Trump campaigned on ending DACA during the 2016 presidential election.

Chavez said that President Trump’s rhetoric during his campaign felt like a stab in the back because it was like he was being criminalized.

“We’ve pretty much grown up here all our life loving this country and everything and, you know, saluting the flag, saying the pledge of allegiance all of my life,” Chavez said. “I don’t know the pledge of allegiance for Mexico because I didn’t grow up there.

“I feel like I am American.”

Go to StateHornet.com/FacesOfDACA for more similar stories on DACA.

Norma • Mar 15, 2018 at 10:56 pm

so proud of all of them!

Preston Nguyen • Oct 5, 2017 at 10:41 am

I thought Eve’s story was powerful and inspirational. He is indeed an American and should not be treated any different just because he wasn’t born here initially. He is kind, honest and most importantly hard working. He will always be someone that people look up to because I believe he is a symbol of hope. He has worked too hard just to be treated the same and I hope others can realize his dedication and devotion to life liberty and the pursuit of happiness.