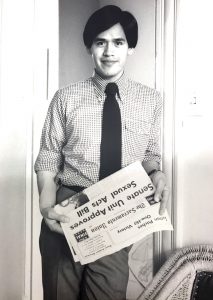

When George Raya requested that the Society for Homosexual Freedom be recognized as an official Sacramento State club in 1970, school officials were uneasy about Associated Students, Inc. granting club status to a group they called “deviants.”

“The police called us ‘unapprehended felons’ — it was against the law to do homosexual acts,” Raya said. “The priests said we were going to hell, that we were sinners. The American Psychological Association said we had a mental illness. So things were rough back in those days.”

Raya, who was serving on Sac State’s student senate, had come out of the closet one year earlier at the age of 19 and was an early member of SHF, a club that included both gay and straight students who wanted to learn more about the LGBT community.

The inspiration for SHF was a similar group at UC Davis known only as C7 — the name of the classroom in which it met.

Martin Rodgers, a psychology professor at Sac State, was called in by the UC Davis administration to investigate if C7 members were in need of counseling.

“Marty went back to the administration and said ‘There’s nothing wrong with them, they’re very happy people (and) well-adjusted,’ ” Raya said. “The only thing, of course, is they’re homosexual.”

Rodgers felt that a similar club for Sac State students would be a good idea, and the first meeting was held in his apartment.

“Every time someone knocked on the door or rang the doorbell, we kind of stiffened a bit because we didn’t know if it was another person coming to attend or if it was the police coming to arrest us,” Raya said.

When Raya proposed that SHF be recognized by Associated Students, Inc., Otto Butz — the acting president of the college — shot down the idea, refusing to approve the group’s charter.

“That case was used by other campus groups around the state and country. If they got denied they’d go to their president and say ‘Look, you lost in Sacramento, you’re not going to win here.’ ” – George Raya, Sacramento LGBT Community Center board member

“He wanted to become the permanent president and he felt that if he granted us a charter, (then-Governor) Ronald Reagan wouldn’t like approving a gay student group,” Raya said.

So ASI filed a lawsuit against both Sac State and the Cal State trustees.

Sac State and the trustees argued that an LGBT club shouldn’t be approved because it would promote what were then illegal sexual acts.

Judge William Gallagher decided the case on Feb. 9, 1971 in favor of ASI, declaring that the school had to recognize SHF because of protections for freedom of speech and assembly in the First Amendment to the Constitution.

“The judge said ‘Look, you can’t deny them based on what you think they will do, they have to have actually done something,’ ” Raya said. “That case was used by other campus groups around the state and country. If they got denied they’d go to their president and say ‘Look, you lost in Sacramento, you’re not going to win here.’ ”

That spring, Sac State held a symposium on the topic of homosexuality headlined by none other than Beat poet Allen Ginsberg.

“The men’s gym was filled to the rafters. Everyone was there to hear Ginsberg,” Raya said. “The day of the speech our boys became flower children and preceded Ginsberg by throwing flowers in his way.”

Ginsberg’s presentation included a reading of his erotic poem “Please Master.”

“Please master can I touch lips to your muscle hairless thigh,” the poem reads. “Please master can I lay my ear pressed to your stomach.”

“I was sitting next the campus librarian and he’s freaking out,” Raya said. “What they wanted was a ‘gay is good’ speech and we got what I call ‘the full Ginsberg.’ ”

Raya graduated Sac State in 1972 with a degree in government and started to go to UC Berkeley for graduate school, but did not finish, saying that his time as a student activist distracted him from academics.

But it was during that time that Raya heard of what until then had been a quiet, working-class Italian-Irish neighborhood in San Francisco.

“One day, a friend of mine who graduated already was telling me about this new neighborhood and it was like ‘Wow, housing was cheap and they had this bar called the Midnight Sun’ — and that’s when people discovered the Castro,” Raya said. “I just lived to dance. I was a disco queen, just every night.”

After Raya’s move to San Francisco, he got involved with a gay rights group called the Society for Individual Rights, which had been co-founded by Jim Foster, the first person to address gay rights in a speech at the Democratic National Convention.

Foster had been discharged from the military for being gay, but had since done work on behalf of 1972 presidential candidate George McGovern and then-San Francisco supervisor Dianne Feinstein. McGovern tapped him to give a speech at the DNC to thank him for his work on his behalf in the primary.

“But McGovern got cold feet. Rather than have this radical image, he started backtracking so he decided to give Jim a 3 a.m. speaking slot,” Raya said. “I waited up to hear him on the radio. Having someone speak out and say ‘I’m gay and I don’t apologize and we want our rights’ was radical for those days.”

Foster and SIR had been wanting someone to introduce legislation that would legalize non-vaginal intercourse among consenting adults. “Sodomy” and “oral copulation” were illegal in California, as in most states, but the laws were rarely used to prosecute heterosexuals.

Most state legislators, however, wouldn’t touch the issue after Reagan announced his intention to veto any change in the law.

When Jerry Brown was elected governor in 1974, then-Assemblyman Willie Brown, D-San Francisco, agreed to introduce Assembly Bill 489 and Raya volunteered to return to Sacramento and lobby legislators for its passage.

“You button-hole people, you talk, you make coalitions,” Raya said. “I’d spend about three or four days a week here (in Sacramento) and would catch a ride with Willie Brown sometimes, which was fun.”

Raya was working for free, and according to a 1975 profile in The Advocate his major sources of income at the time were “friends and family, food stamps and the $6 a pint he sometimes receives for selling his blood plasma.”

Partly thanks to Raya’s lobbying, the bill passed and was signed by Governor Brown in 1975.

His efforts also earned him the attention of the National Gay Task Force (now called the National LGBTQ Task Force), and in 1977 he joined NGTF members in the first-ever meeting about LGBT rights held at the White House.

Then-President Jimmy Carter had left for Camp David when presidential advisor Margaret “Midge” Costanza brought her girlfriend Jean O’Leary, then-co-director of the NGTF, and a contingent of fellow LGBT rights activists to the Roosevelt Room to meet with White House staffers.

“It was great — first time gays were in the White House,” Raya said. “Each of us was given a department of the federal government to speak about how they could improve regarding the LGBT community. I picked hepatitis, which was a big killer.”

Hepatitis was one of several sexually transmitted diseases spreading in the age of sexual liberation, and Raya felt the government wasn’t doing enough to educate people about the risks.

“Everyone in the meeting up until then was saying ‘Thank you Midge for the opportunity to be here,’ ” Raya said. “But when I said ‘We need to do something about hepatitis,’ I got daggers.”

Nonetheless, the federal government conducted a study about hepatitis in San Francisco from 1978-80, “which really helped out later,” Raya said. (Story continues below)

1977 was also the year that Raya threw his support behind Harvey Milk, the first openly gay member of the San Francisco County Board of Supervisors and one of the first openly gay politicians in the country.

“I didn’t support him the first three times he ran. He was new to the city,” Raya said. “Jim Foster told him once ‘We’re like the Catholic Church: we accept converts but we don’t make them pope the next day.’ ”

Raya was in an opposing faction of the city’s Democratic Party as Milk, but campaigned for him nonetheless.

“Instead of billboards, we had human billboards where 12 people would stand there on the corner with signs that said ‘vote for Harvey Milk,’ ” Raya said.

But not everyone in the gay community was behind Milk’s candidacy. David Goodstein, publisher of The Advocate, was initially one of those.

“David wanted to make peace with Harvey,” Raya said. “Harvey said ‘no.’ So I called David (and said) ‘He’s still crazy.’ But after the election, he was in every photograph with Harvey. He organized a big-ticket fundraiser for Harvey. At the next table was Dan White.”

White, who was also elected to the board of supervisors that election, assassinated Milk and Mayor George Moscone in San Francisco City Hall on Nov. 27, 1978, after Moscone refused to reinstate him as a supervisor after he’d resigned.

When White was only sentenced to seven years in prison — his lawyers argued he’d been impaired by excess junk food, in what came to be known as the “Twinkie defense” — the San Francisco gay community erupted in riots.

The double murder was only the beginning, however, of the group’s troubles over the next decade.

“Instead of billboards, we had human billboards where 12 people would stand there on the corner with signs that said ‘vote for Harvey Milk.’ ” – George Raya, Sacramento LGBT Community Center board member

“On 18th and Castro, there was this pharmacy and in 1981 they had on the windows outside Polaroid shots of people with (Kaposi’s sarcoma) and it said ‘If you have this, see a doctor,’ ” Raya said. “By the time the symptoms showed, you weren’t long for this world.”

Until HIV/AIDS began to spread, Kaposi’s was a rarely fatal skin cancer common among older men with Mediterranean backgrounds. But in the 1980s, the purple lesions became a sign of imminent death.

“People went to the hospital and died the next day,” Raya said. “Over half the people in my address book were dead. I got tired of crossing out names so I put them in pencil.”

Raya became a co-founder of the Latino AIDS Project after he could only find one piece of informational literature on AIDS that was written in Spanish.

“The mainline AIDS organizations were run by whites, for whites,” Raya said. “One video we made earned $100,000 because it was the only one in Spanish. We sold so many it was incredible.”

Raya took a class in how to care for AIDS patients, training which he found helpful when his father in Sacramento became ill with lymphoma, which he died from.

Raya came back to Sacramento initially to care for his father, but after his death Raya decided not to return to the Bay Area.

In Sacramento, Raya, 67, serves as a board member of the LGBT Community Center on 19th and L streets.

David Heitstuman, the executive director of the center, said that Raya is “one of the most dedicated, hardworking, tenacious board members.”

“I think that a lot of people believe that because there’s higher visibility of LGBT people in popular culture that people aren’t being kicked out of their homes anymore,” Heitstuman said. “40 percent of homeless youth are LGBT. People still have violence committed against them. The number of new HIV infections are rampant among young people. I think George’s perspective and being able to share his experiences with this for his whole life is important.”

For his part, Raya has decided the biggest difference he can make now is on the local level.

“I’m blown away that I’m still alive,” Raya said. “I take it as a responsibility — I’ve got to do something.

“In 1969, when I came out, I wanted to read everything I could about homosexuality and there was a new law book: ‘Homosexuals and the Law.’ The writer said ‘The prejudice is not going to change until the gay community can advocate for itself.’

“That’s why I went full-steam.”

UPDATE: April 13 at 11:26 a.m. — This article has been updated to reflect that David Heitstuman said 40 percent of homeless youth are LGBT, not 46 percent of homeless people.

Jerry Pritikin • Apr 13, 2017 at 7:58 am

George has always been in the front line of the gay rights movement and has not slowed down one bit. He has been a great leader and still is… and a great roll model for those getting involved in civic and political fields. Like George, I did not embrace Harvey Milk, even though he was openly gay and Jewish like myself. In the race when Harvey won in 1977, I supported Terry Hallinan, who I thought could best serve the people of the 5th District of S.F.because he was better qualified.Sadly, among those who supported Milk,were hetero-phobic gays, who accused Terry of being anti-gay. However, Harvey and I always remained friends. Harvey won, because he had mostly honorable people supporting him and George was one of them.