The LGBT community has certainly come a long way from when Sacramento State argued that a gay club shouldn’t be allowed on campus because LGBT people were “unapprehended felons.”

Yet, the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision that recognized same-sex marriage as a constitutional right certainly doesn’t mean that the struggle for equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender people, and others who don’t fit expected sexual and gender roles, is over.

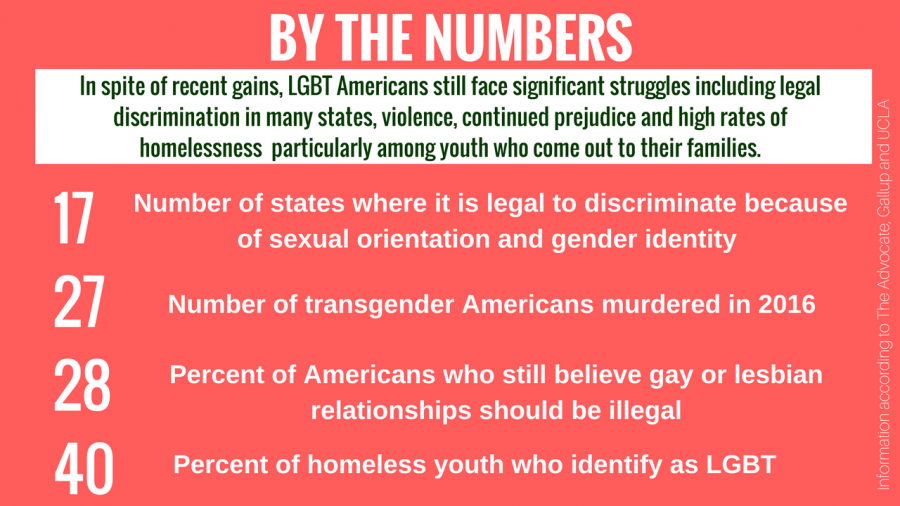

For example, in 17 states it is legal — even for the state government — to discriminate in employment on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. In 28 states, it is legal to discriminate in housing against LGBT people.

These issues are left to the states because there is no federal law completely banning discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, while federal laws do exist to prevent racial, religious or gender discrimination.

On April 7, the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sex also applies to sexual orientation, but the 11th and 2nd circuits came to opposite conclusions in similar cases, which sets up the issue for a Supreme Court battle.

But with Donald Trump in the White House for the foreseeable future — and already having one pick for the Supreme Court under his belt — foreseeing how long the Supreme Court will remain a protector of LGBT rights is a purely speculative exercise.

Just last month, President Trump rescinded an Obama executive order requiring federal contractors to provide documentation showing that they do not discriminate. He also rescinded Obama’s guidelines allowing transgender students to use the bathroom of their choice.

Even when they are positive, however, changes in the law can only do so much. 2016 was the deadliest year on record for transgender individuals, with 27 killed in the United States that year, according to The Advocate.

And as of March 22, eight transgender people have been killed thus far in 2017, according to The Advocate.

A substantial majority of the victims in both years have been transgender women of color, and the numbers are likely understated because of some murders going unreported and victims being identified by biological sex.

“The most important thing allies can do is to listen to the LGBT people in their lives and try to understand that the reason for political advocacy is the dignity of the people themselves: people who time and time again have proven resilient in the face of opposition — and who certainly will again.”

Forty percent of homeless youth are LGBT, according to a 2011 UCLA study, and 68 percent were kicked out of their house once their sexual orientation or gender identity was revealed to their families.

In the world of sports, there has certainly been change but there is still a strong current of anti-LGBT sentiment.

Statistically few players in the NFL, MLB and NBA have come out — and most of them after retirement. In the NFL, for example, there are currently no openly gay players; six came out after retirement, and only one has ever been drafted (Michael Sam was released by the Rams before the start of the season, however).

And in spite of the progress of the past several decades in LGBT equality, about one-third of Americans remain opposed to same-sex marriage and 28 percent maintain that sex between consenting adults of the same sex should be illegal, according to a 2016 Gallup Poll.

And so, increased visibility and some equal rights do not mean that discrimination, fear and alienation are issues that the LGBT community no longer has to face.

There is always the temptation in a social movement to stop paying attention and pushing the envelope once a major civil rights landmark has been achieved.

For example, the struggle for women’s rights went through a lull in the 1950s, with many women returning to the home after being employed during World War II.

LGBT people and their allies have to continue to make their voices heard — and not just on social media. Activists like Harvey Milk and George Raya used old-fashioned organizing tactics and groundwork to affect political and then legislative change.

And considering that the LGBT community is smaller in size than many other historically marginalized groups, keeping up the pressure is even more imperative.

For allies, it can be tempting to take a paternalistic attitude toward LGBT people and to view them primarily as an interest group to protect.

But the most important thing allies can do is to listen to the LGBT people in their lives and try to understand that the reason for political advocacy is the dignity of the people themselves: people who time and time again have proven resilient in the face of opposition — and who certainly will again.