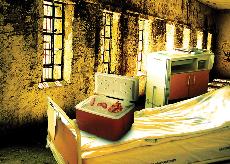

Ripe for the harvest

Ripe for the harvest

April 22, 2009

There’s a little pink sticker on my driver’s license. It’s there to tell doctors that when I die my organs can be donated to people who need transplants.

Next time I renew my driver’s license, I’m taking that pink sticker off.

Why?

I’m scared for my life.

Wesley J. Smith, an attorney and activist for universal human rights, came to Sacramento State on April 7 to speak out against a theory that is catching on with bioethicists around the world. The theory justifies removing organs from patients who are in vegetative states, thus killing them.

It’s called the personhood theory, and it seeks to define what makes a person different from things that are not a person. So far, “personhood” applies to any organism that has the ability to display high-level thought.

Examples of higher-level thinking are: having a sense of time and its passing, being smart enough to be aware of yourself and valuing your own life. Anything that doesn’t conform to this is called a nonperson.

You didn’t misread that. There really is a growing number of bioethicists in America who don’t see all human beings as being people.

Since people who are in a vegetative state do not show any signs of higher-level thinking, a growing number of people in the bioethics community believe that harvesting their organs would be a better alternative to keeping them alive.

Best of all, vegetative patients wouldn’t be the only nonpersons eligible for harvesting. Under the criteria laid out, Smith said the term “nonperson” could include patients who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease or some other mental illness that causes people to lose their ability to properly process the world around them.

“Personhood (theory) tells us we can kill and get a good night’s sleep,” Smith said.

To be fair, the theory isn’t as heartless as Smith believes it to be. As of right now, 101,520 people are on the national waiting list for organ transplants, according to OrganDonor.gov. Personhood theory argues that if patients are in a permanent vegetative state, then there’s no point in keeping him or her alive, especially when his or her organs could be used for a better purpose.

But what if we’re misdiagnosing people as being in a permanent vegetative state?

Dr. Lawrence R. Huntoon wrote in an editorial in the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons that patients are misdiagnosed as being in a permanent vegetative state 18 to 40 percent of the time.

Considering the fact that there are as many as 25,000 cases of patients who were diagnosed as being in a permanent vegetative state, if Huntoon’s statistics are correct, we could be wrongfully ending up to 10,000 lives.

Of course, this all hinges on the pretext that the patient had given consent to be an organ donor.

“With such consent, there is no harm or wrong done in retrieving vital organs before death, provided that anesthesia is administered,” according to a 2008 New England Journal of Medicine article.

Apparently, the doctors who wrote this article missed the portion of the Hippocratic Oath that says they will “perform the utmost respect for every human life from fertilization to natural death.”

Removing vital organs from patients can hardly be considered a “natural” form of death. Despite that, many personhood theorists would have little problem with the blatantly unethical practice.

And until the medical community officially condemns personhood theory and the practice of harvesting organs from living patients, that little pink sticker is staying off my driver’s license.

David Loret de Mola can be reached at [email protected]