The changing face of sports

Claire Padgett

March 11, 2009

Title IX was federal legislation passed in 1972 that forced schools that received federal money to ensure gender equality.

The text of Title IX of the Education Amendment is fairly straight forward: “No person in the United States shall on the basis of sex, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Since its passing in 1972, it has caused controversy on college campuses across the country. While it never specifically mentions sports, athletic departments have had the toughest time grappling with implementing Title IX.

In particular, men’s teams have seen a steady decline in the number of programs available.

In its “Intercollegiate Athletics: Four-Year Colleges’ Experiences Adding and Discontinuing Teams” report, the United States Government Accountability Office attributed this decline to the need to reallocate budgeting to comply with Title IX requirements.

Lois Mattice, senior women’s administrator in the Sacramento State athletic department, said Sac State has had to comply with tougher rules due to a 1992 lawsuit filed by the California National Organization for Women (CA NOW) against the California State University system. Called the CA NOW consent decree, it requires CSUs to report annually on gender equality in participation, scholarships and equipment/facilities. One of the people at the forefront of the lawsuit was Mary Zimmerman.

Zimmerman was the former women’s athletic director at San Jose State. When women’s sports were brought under the umbrella of the NCAA in 1987, she was made associate athletic director.

“When they combined them, the athletic director that was there decided the emphasis was to be football and men’s basketball,” she said. “San Jose State had a very strong female athletic program in the 1970s and 1980s. All the work that we had done for women’s sports was being dismantled.”

Zimmerman, along with CA NOW, sued San Jose State and the CSU system to force Title IX compliance, and won.

“I think Title IX has had a dramatic change,” said Kathy Strahan, head coach of the Sac State softball team. “I go back to my playing days, to now. We didn’t know what a scholarship was when I was that age. There has been tremendous improvement.”

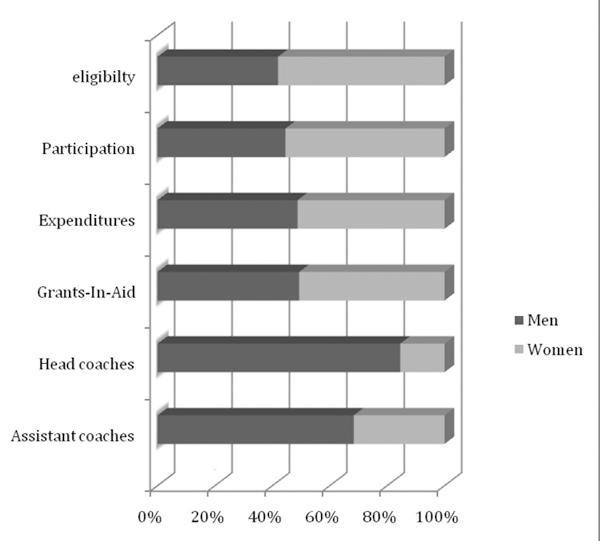

According to a CSU report on gender-equity in sports, female participation in intercollegiate athletics has increased 106.2 percent over the past 13 years.

The gender-equity survey, “Voluntary self-monitoring report regarding equal opportunity in athletics for women students, annual report 2005-2006,” reported that 55.4 percent of the participants in Sac State-sponsored athletics are women.

According to the “Women in Intercollegiate Sports” survey by Vivian Acosta and Linda Jean Carpenter from Brooklyn College, because of Title IX, “more college women have more athletic teams available to them than ever before.”

Despite these new opportunities, the number of women coaches and administrators have seen a marked decline.A look at the HornetSports website shows only 15.4 percent of the head coaches (2 out of 13) are women.

Mattice said it is difficult to find qualified female candidates for head-coaching positions.

“When we are hiring, we are always looking for the best person for the job,” Mattice said. “Currently there aren’t very many women out there seeking jobs as head coaches. It’s not a great job as far as having a family. At this level, it’s very hard to have a family.”

Zimmerman said that while she is thrilled with the strides in participation, she is disappointed in the decline of women coaches.

“Initially, 90 percent of coaches of women’s sports were women,” Zimmerman said. “But as soon as Title IX came it also caused the salaries and identification for girls sports to improve. So there was more people coming for jobs, and since it was mostly male athletic directors, they would hire those they were most comfortable with, which were men. We quickly went from 90 percent down to 50 percent of (women) coaches.”

According to Acosta and Carpenter’s survey, 90 percent of coaches of women’s teams were female prior to the passage of Title IX. At the time of their study in 2004 the number was 44.1 percent and getting smaller.

Keri Elias, junior infielder on the Sac State softball team, had always been coached by men before coming to Sac State. “Most guy coaches I had were baseball players who never played softball,” she said. “Women can relate more to girl problems and to actually playing the sport. Our coaches played our sport at the same level as we are playing.”

Mike Connors, Sac State women’s rowing coach said: “In the coaching ranks themselves it has taken a while for women to be coaching women and there still is lots of head coaches that are men. It’s slowly changing. You see that in rowing, especially in assistant coaches. It’s also a choice. They have to want to do it to make it a career.”

The Acosta and Carpenter survey discovered that only 2 to 3 percent of men’s teams are coached by a female head coach and only 20.6 percent of all teams are coached by a female head coach.

The survey said, “Women have also lost leadership of women’s sports. In the pre-Title IX era, women held almost all administrative positions in women’s athletics programs. Today, almost all of those programs are merged with men’s, and less than a fifth of athletic directors are women. They account for fewer than one in ten directors of athletics in Division I schools.”

One of those rare 2 to 3 percent of female head coaches in charge of a men’s team is Kathleen Raske, director of track and field and cross-country at Sac State. As director, she coaches both the men and women’s teams.

“As a female coach, you always have to prove yourself,” Raske said. “Not just once, but you constantly have to prove yourself. Female coaches are held to a higher standard.”

Mattice said both men and women sometimes have difficulty being coached by a female head coach. “A lot of girls prefer a male coach,” she said. “That’s because they grew up with their dad being their coach. Their role models may not be female coaches because they grew up with male coaches.”

Kelly Shepard, freshman outfielder for the Sac State softball team, said she has played for both men and women coaches.

“I think both are great to have, because they treat you differently,” she said. “I think it is great to have different types of coaching staffs. People see women coaches as different. They think they aren’t as aggressive or aren’t as competitive as the men.”

Marlene Bjornsrud is the founder and CEO of the Bay Area Women’s Sports Initiative. She has been involved in women’s sports for more than 30 years.

She sees a number of reasons for a decline in women head coaching. “The old-boys network is strong and, with most athletic directors being men, they are more inclined to hire men,” she said. “Women also are less inclined to stay in jobs that require 24-7 attention and travel. Women also now have more choices outside of sports.”

Zimmerman said women’s teams had a large number of women coaches because it was one of the few career paths for women. “The other thing Title IX did was open up vocations for women. Prior to Title IX we could be secretaries, teachers, coaches or nurses,” she said. “If we get the best and brightest, they might want to do something else – a doctor or lawyer or whatever they want to do. It’s all part of the unintended consequences.”

Strahan hasn’t seen many of her softball players go onto careers in coaching. “I don’t think many come in with coaching on their mind. About a third of my team is usually criminal justice majors. If you are a criminal justice major here in the state of California you can get a job paying $50-$60,000 a year. In coaching you are going to be a graduate assistant making $20,000 a year and go somewhere else. If you want to stay in the area, coaching might not be an option.”

Bjornsrud said while it might be harder to encourage women to be coaches, there isn’t an effort being made.

“Girls need to see strong women in their lives,” she said. “The old-boy network needs to be dismantled. An athletic department looks different when strong women are involved. It gives it a more holistic look and feel.”

Dani Thole, senior Sac State rower, hopes to become a rowing coach after she graduates from Sac State.

“In high school, there was a male coach who tended to treat the men’s team more fairly and then the women’s team he didn’t really seem to care about,” she said.

Mike Sagas of the University of Florida co-wrote an article for the journal “Sex Roles” that found women are much more likely to be hired as assistant coaches than head coaches.

“The data clearly show there is still a ‘good-old-boy’ network out there, a mindset in which men would still rather hire other men as head coaches,” Sagas said. “Currently, the ‘good-old-girl’ network for women is less prevalent at the highest levels of athletics administration. So when it comes to being hired for the head job, men are more often hired.”

Dan King can be reached at [email protected]