When Sacramento State’s Director of the Disability Access Center, Mary Lee Vance, was first approached about the possibility of a Disability Cultural Center by students, she wasn’t optimistic about it due to a lack of space offered by the university.

In 2020, Vance acquired room 2011 in the Academic Information Resource Center and got rid of old technology that became defunct during the center’s transition to a more digital layout.

“As the space started opening up, I started to visualize,” Vance said. “We had all this open space and I thought, now’s the time.”

Housed under the DAC, the Disability Cultural Center officially opened fall 2023 to provide modified technology equipment, adaptive board games and a new sensory room. The DAC brought services to disabled students on campus back in the ‘70s under Section 504 of the Rehabilitations Act.

Previously known as Services to Students with Disabilities, the DAC provides a variety of accommodations to “ensure disabled students have equal educational access,” according to their website.

The Disability Cultural Center differs from the DAC as it is moreso a safe place for disabled students and allies to come together. A Disability Cultural Center was a dream of many past DAC students, Vance said.

“Growing up with a disability, you end up in a social bubble,” said Shannon Noel Brown, the center’s administrative specialist. “What we want to do with the new Disability Cultural Center is help our students open that bubble up.”

Before receiving accommodations, 34-year-old Kirsten Johnson said she thought the expectations were “lowered” for disabled students.

“I’m still having to do all of the same work,” Johnson said. “I just have a little bit of extra time to do it. I’m still struggling, but it’s the difference between how much I’m struggling now versus what I would have without those accommodations in place.”

Johnson, a disabled, wheelchair-using student with ADHD, transferred last spring and has received accommodations every semester she’s been at Sac State.

As a physics major with a minor in astronomy, she said she chose to transfer to this university because the campus’ planetarium is more accessible by wheelchair than the other CSU campuses she visited.

Johnson said she was born with her feet facing each other. While she couldn’t really stand on her own and walk, it was still possible for her to run and dance.

It wasn’t until Johnson started working in retail as an adult, having to stand up for eight or more hours a day, when she said her disability started to get worse.

After learning she had posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, she said she had total reconstructive surgery on her feet in 2020.

“It was supposed to make everything better,” Johnson said. “We have not figured out why but it just hasn’t, and actually my pain now is worse than it was before the surgery.”

Johnson said she ultimately didn’t have the option of going without accommodations when she transferred like she previously did at the community college she attended in Texas, because the pain forcing her to use a wheelchair got worse.

While Johnson said she feels supported as a disabled student, she noticed that the front desks in classrooms typically reserved for disabled students are not positioned where they’re supposed to.

“During the course of the day, desks get shifted around,” Johnson said. “Some professors will use that accessible desk as a lectern and then not move it back at the end.”

On days when Johnson wants to eat outside or simply appreciate the weather her chances go out the window when all the wheelchair-accessible tables are taken around campus.

Most chairs are bolted down into the floor, however she did note that the AIRC located near the library has chairs that she can move around if she needs to make an accessible space for herself.

In the end, Johnson said she feels removed from the disabled community on campus.

“I have only been here since January, but I feel disconnected from other disabled students,” Johnson said. “It’s difficult to find a way to connect.”

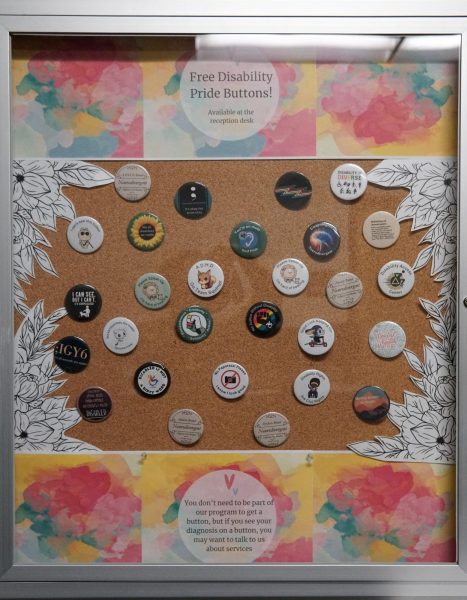

One way the Disability Culture Center provides accessible spaces for students is through a sensory room, which Vance said is the first on a CSU campus. The sensory room includes dimming lights, fidget sensory toys, ear plugs and many other items that cater to the neurodivergent population on campus.

With the opening of the cultural center, it would allow a new representation of the disability community that hasn’t been recognized on campus before, according to Brown.

“If you don’t see our disability, then you’re not representing us at the table,” Vance said.

Larry Riel, a 24-year-old public health major with a focus on community health education, said he hopes to work in queer health equity and disability justice spaces, being a voice for those who are overlooked in healthcare.

Riel was 13-years-old when he said that it first “clicked” that he’s transgender. His mental health started getting worse immediately after, when he had to come to terms with the fact that he now lived in a “much more dangerous world” because of the way he identifies. He then started developing symptoms of bipolar disorder and OCD but didn’t receive a proper diagnosis until he was 16-years-old.

Five months after being diagnosed, Riel said the discrimination and abuse he was subjected to as a queer person resulted in a hospitalization for the first time. It was also during this time that he was diagnosed with autism.

Riel is in his first semester as a full-time student at Sac State, and he said he’s glad that the DAC offers services to disabled students.

“When I tried going to [community college] in 2017, I was full time and I dropped out,” Riel said. “I was put in a psych ward for the second time, so I’m hesitant about coming back full time.”

Riel said he’s provided extra test-taking time through his accommodations. Sounds such as pen tapping or the clacking of nails distract him, and he can find the lights too bright to focus sometimes.

“I can do really well,” Riel said. “Sometimes I need a little bit of support, because I can work. I have the ethic. I just can’t control the brain that I have.”

While Riel was able to receive accommodations because he provided documentation of his diagnoses to the DAC, he said it makes him angry that no one talks about those who have disabilities but can’t get a proper diagnosis. He said that their voices matter, too, even if they’re not “part of a countable statistic.”

Riel said that professors should be accommodating to disabled students’ needs, even if they haven’t applied for services through the DAC.

“For a lot of folks, they can’t get that diagnosis because that cost thousands of dollars for an assessment,” Riel said. “Or maybe some of us don’t get diagnosed because it’s safer.”

Riel also said that concerns of safety and privacy make it difficult for disabled students to find and meet each other.

(Jasmine Ascencio)

“Building a community of disabled students requires people to share that they are disabled,” Riel said. “They might do so if they know the other person interacting with them is also disabled, but also a lot of disabled folk really do not wanna disclose that.”

Brown and Vance also shared that the DAC will launch a Sacability Mobile App in October. The app will allow students within the center to socialize, meet and interact with one another in a safer environment.

“If you got the buddy app or if you go into the Disability Culture Center, you can kind of feel like at least I’m in a space where someone will at least partially understand who I am,” Vance said. The app will be completely available in October, just in time for the center’s open house event.

The DAC will be having an open house event for their new Disability Cultural Center on Oct. 18 from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

For more information about the DAC and the services they provide, visit their website. The DAC is located in Room 1008 in Lassen Hall and the new Disability Cultural Center is in Room 2011 in the AIRC.