Sac State Indigenous students and educators reflect on what Thanksgiving means to them

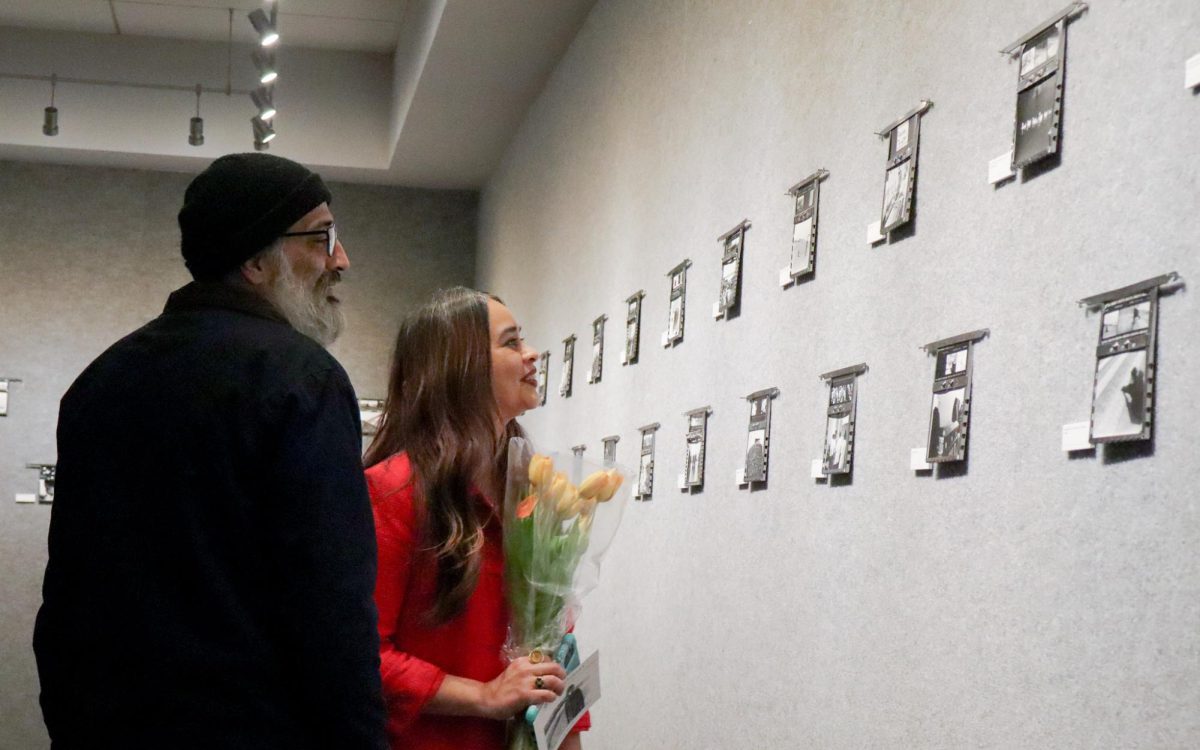

Al Striplen is a retired professor and counselor at Sacramento State as well as a teacher of Native American flute. He said that he separates his Indigenous heritage from Thanksgiving, in order to participate in the holiday.

November 27, 2019

The first Thanksgiving was held sometime between late September and early November in the year 1621 at the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, according to the California State Indian Museum, a three-day feast held between colonists and Indigenous men.

It is estimated that somewhere between 5 and 15 million Indigenous people lived in what is now the United States when Christopher Columbus arrived. At the end of the Indian Wars in the late 1800s, less than 286,000 Indigenous people remained.

To this day, many Indigenous people live in poverty and face a variety of social and health issues. For many of them, Thanksgiving represents the beginning of these problems.

Yadira Ramirez, a women’s studies major at Sacramento State, is of Indigenous descent through the Apache Nation in the Mescalero Apache Tribe. She is also Yaqui from her father’s side.

Ramirez said that growing up, her family always celebrated with the usual turkey dinner. It wasn’t until she learned more about Indigenous history that she began to influence a change in her family’s holiday routine.

“This year, my family will not be celebrating Thanksgiving, and instead, will be attending the Sunrise Ceremony on Alcatraz Island Thursday morning,” Ramirez said. “This is a space where Indigenous folks and allies gather to mourn the atrocities that took place on ‘Thankstaking.’ We hold ceremony, pray and honor our ancestors and the land as a way to show our gratitude for their resilience.”

Ramirez said the consciousness around the holiday has changed due to social media and spreading of the true history of Indigenous people in the United States.

“More and more Indigenous folks are coming together and mobilizing to protect our land and our rights,” Ramirez said. “I have seen more anti-Christopher Columbus Day posts this year as well as folks supporting the fact that Thanksgiving is not this happy, cheerful holiday that it is made out to be.”

“People are becoming more conscious and are questioning the wrongful history that has been taught in these institutions about this racist ‘holiday.’”

Ramirez said that it is important to remember the Indigenous people killed and stripped of their rights by colonialism throughout “Turtle Island,” a phrase often used by Indigenous people to represent North America.

“How do you pay respects to the land and Indigenous peoples? What are you doing with your platform and privilege to educate others on this day and on Indigenous rights?” Ramirez asked.

Sacramento City College freshman Edith Williams is federally recognized as a member of Wilton Rancheria of the Miwok people and claims Concow, Miwok, Wailaki, Wintun and West Shoshone ancestry.

Williams said Thanksgiving represents the beginning of the attempted genocide of Indigenous people, but also acknowledged that the concept of Thanksgiving as a time for family and friends to gather and feast should be celebrated.

Williams urged people not to overlook the facts of racial discrimination involved in the holiday.

“The United States didn’t give us Indigenous people any papers, which meant we were illegal on our own land,” Williams said. “Many Indigenous people were ripped from their families to be in the boarding school that my great-grandma was in. It doesn’t only hurt us but makes me furious.”

Williams is a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women advocate and works to keep Indigenous traditions and celebrations in practice. She said it was only 40 years ago, when the Religious Freedom Act of 1978 was passed, that ceremonial traditions were legalized to be practiced through the right to access sacred land and the use of objects considered sacred.

Al Striplen is a former Sac State professor and counselor that taught Native American studies and a member of Amah Mutsun Tribal Band of the Ohlone people. Striplen chooses to celebrate Thanksgiving despite its history.

“I don’t need to hold tight to social practices,” Striplen said about Thanksgiving. “I disassociate it with the historical records, it interferes with my concept of thanks. The truth of the matter, spiritual-wise, is consciousness attached to heart as opposed to consciousness attached to history.”

Jocelyn Reeves • Feb 20, 2020 at 6:44 pm

I will be visiting Sacramento State University for a conference soon and would like to know if there is a formal traditional acknowledgment the university uses to acknowledge and honour the traditional land upon which the university resides.

For example, in British Columbia Canada (where I am from) we have developed several traditional acknowledgments that can be used when visiting a place and as an “authentic ally” I would like to be able to do the same when visiting your university.

Thank you.