Pay rates for Sac State faculty lower than most CSUs

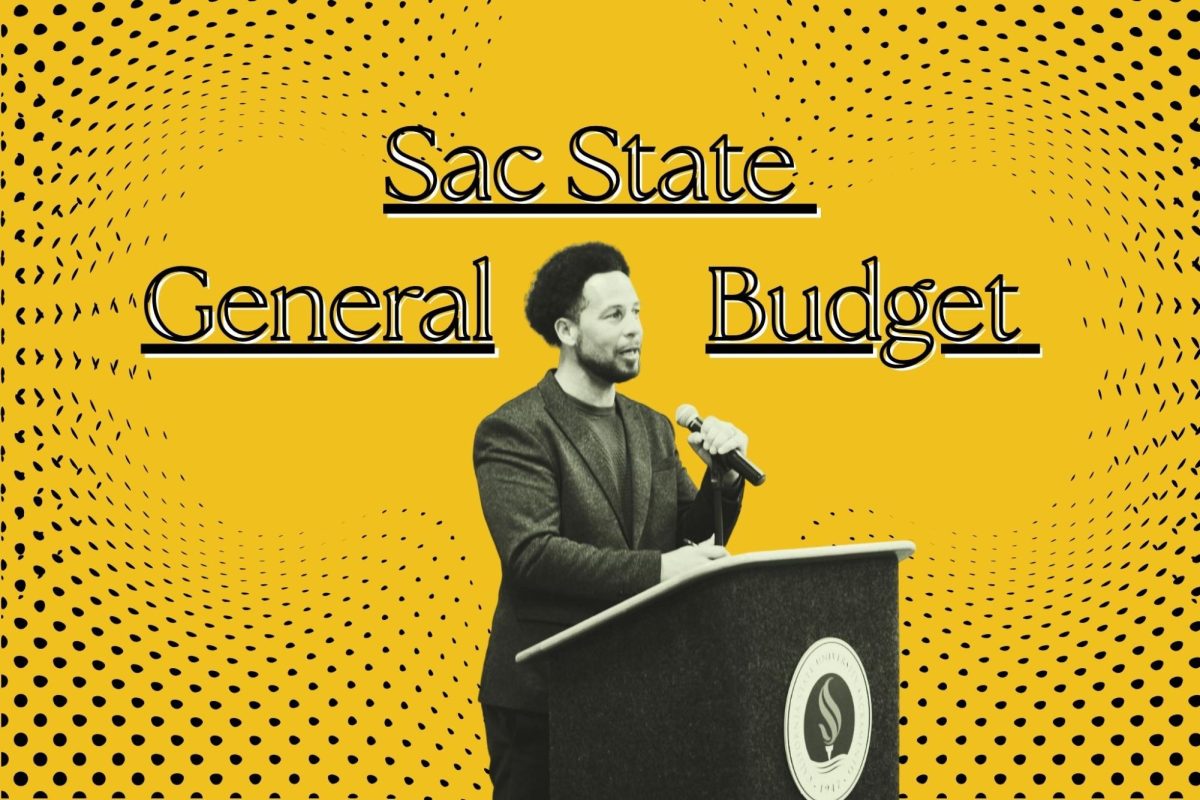

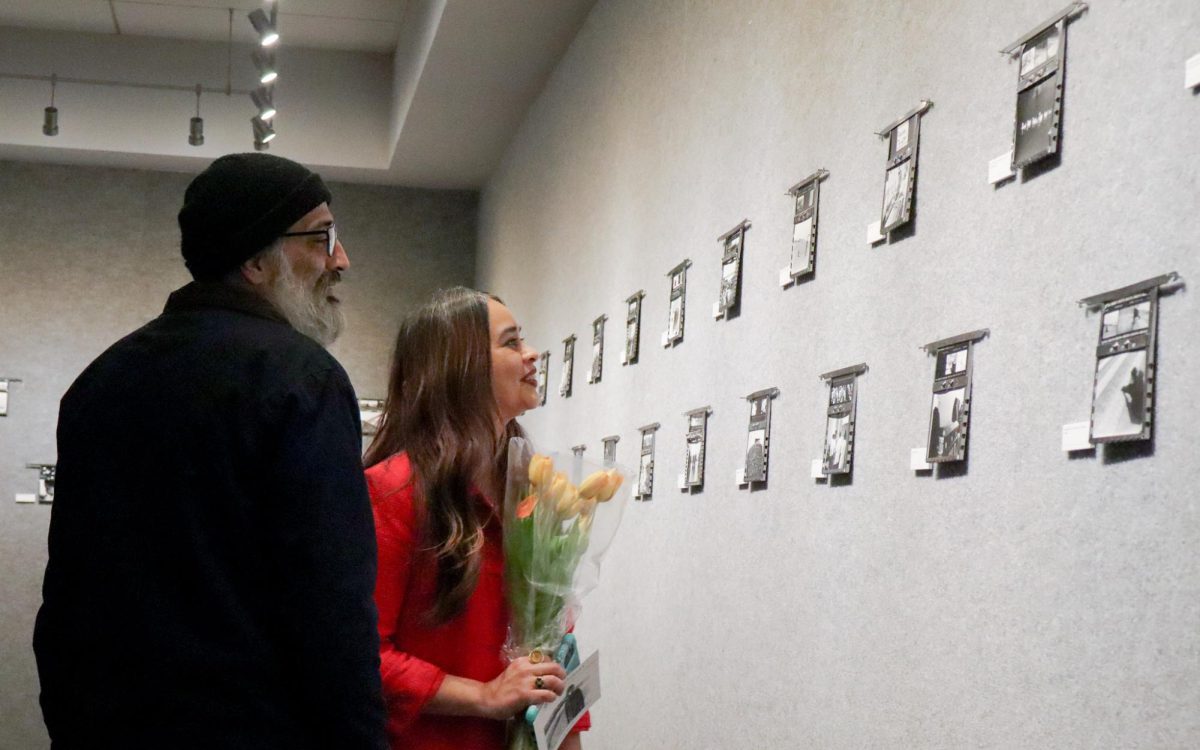

(Photo courtesy of Nisha Gates, California Faculty Association)

Kevin Wehr, a sociology professor at Sac State, speaks to a rally crowd outside of the California State University Chancellor’s Office in Long Beach, California. Wehr was formerly head of the Sac State chapter of the California Faculty Association.

March 14, 2019

Full-time professors at Sacramento State rank lowest in average annual salaries in the California State University system, according to data from the American Association of University Professors.

Associate and assistant professors — while not at the bottom — ranked lower on average than most of the other 22 schools in the CSU system.

Story continues below chart.

Margarita Berta-Avila, president of Sac State’s California Faculty Association chapter said that issues were not resolved in the slightest under former President Alexander Gonzalez, who stepped down in 2015.

Berta-Avila said that while some progress has been made under current President Robert Nelsen, the issues are solved or at a sustainable level of improvement.

“It wouldn’t have been so bad if we had received our (general salary increase), but that didn’t happen,” she said.

General salary increase, also known as GSI, is a phrase used to describe a raise for faculty across the CSU system.

“The faculty still struggle. We were able to obtain a six percent raise for faculty, which they’re super thankful about,” Berta-Avila said.

According to Berta-Avila, the six percent raise received was separate from GSI.

Story continues below chart.

Berta-Avila added that the GSI never occurred in the years after the recession, so despite the recent raise, long-standing faculty never got full payments they were supposed to receive.

Kevin Wehr, a sociology professor at Sac State and former president of CFA prior to Berta-Avila, shared similar sentiments.

“In 2009 through 2011, there were some scheduled raises that were not paid due to a lack of budget,” Wehr said.

Berta-Avila said the school’s faculty have been dealing with inversion and compression issues since the Great Recession in 2008.

Wehr defined inversion as somebody with less experience or newly hired earning more than an established employee. He defined compression as a group of employees within a set time frame of employment — such as five employees all in the range of 15 to 20 years of service — getting paid the same amount.

“It was pretty significant for a lot of faculty,” Wehr said. “A lot of faculty (who taught at the school then and now) feel that was a wrong that has not been corrected.”

Berta-Avila and Wehr both mentioned that the phrasing, “Faculty working conditions are student learning conditions” is used often in negotiations with management about faculty salary.

“(The faculty) are invested in the institution, they want the institution to improve,” Berta-Avila said. “If faculty aren’t taken care of, they’ll leave. And many leave.”

Wehr also brought up other factors, such as class size and general hiring practices, but stuck to the idea that faculty should be held in higher regard.

“To be totally blunt, buildings aren’t worth much if there’s no faculty to teach in them,” Wehr said. “Investing in faculty is one of the most important things the university can do — in fact, I’d argue it’s the most important thing.”

For some professors, teaching isn’t all about the money.

Andrea Walters, an economics, part-time professor at Sac State, discussed some of the aspects of teaching beyond pay rates that are to the benefit of instructors at large.

“One of the benefits of this job is flexible hours. Flexibility is part of my compensation,” Walters said when discussing the ups and downs of the job as a whole.

From an economic perspective, Walters described just how complex the dichotomy of salary rates compared to the reality of the job is.

“Increasingly, universities are hiring more people like me instead of those full-time faculty because it’s a lot cheaper,” Walters said. “I make somewhere between one third and one-quarter of what everyone else makes, which is cool because it saves the school a lot of money and a lot of schools are doing that.”

Walters added that while teaching at CSU Los Angeles, where she taught before coming to Sac State, two-thirds of the faculty were part-timers.

“So, the short answer is… I don’t know,” Walters said. “I don’t think there’s a good, easy solution because how people learn is a really complicated process,” Walters said.

Walters said there were trade offs to the lower overall salaries at Sac State, including advantages such as flexible schedules, having the summer months off as an option and benefit packages that faculty and employees at large can receive.

“I’ve had people I work with say, in political science, where we do similar work, but economists just make more because our private sector options are better,” Walters said. “So that feeds into some dissatisfaction.”

Henway Fong, a computer science major at Sac State, said he’s had professors in the past that have had to balance second jobs with teaching.

“I think it does affect quality,” Fong said. “You’re not fully focused on one task and one job.”

Fong said he believes educators shouldn’t have to worry about financial issues, as (a higher faculty salary) would be to everyone’s benefit in the institution otherwise.

“Not only does it bode well for the students and the quality of education, but for the school as well. It makes the school look good,” Fong said.

While there may not be a clear fix, Wehr described starting solutions for a better overall environment.

“One thing the campus could do right now is address cases of inversion and compression by gender and race,” Wehr said. “If those issues exist, they should be fixed.”

John • Mar 16, 2019 at 7:47 am

As someone who has worked at multiple CSUs, I can tell you that staff pay is lower at Sac State as well. Staff and faculty are aware of the pay disparity and it definitely imapacts morale.

Deadlord • Mar 15, 2019 at 5:10 pm

Don’t matter cause Sacramento is Cheaper than other places in CA.