Cambodian students learn about own roots in ‘First They Killed My Father’

Courtesy of Netflix

Making her on-screen debut, 9-year-old Sreymoch Sareum portrays Loung Ung in “First They Killed My Father,” a Netflix original film by Angelina Jolie that follows the true story of a 5-year-old girl struggling to survive life in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge regime.

October 10, 2017

A new Netflix film directed by Angelina Jolie reveals an unspoken history of Cambodia, prompting many members of the Cambodian community to gather family and friends to watch it together.

The film, “First They Killed My Father,” is based off of a 2000 novel memoir by Loung Ung, who recounts her time as a child living in Cambodia from 5 to 9 years old. The story is set during the late 1970s, a time when the Khmer Rouge rose to power and gained control of the nation.

Its leader, Pol Pot, wanted to turn Cambodia into an agrarian society and forced people to abandon their urban lifestyles to become laborers in the countryside. Nearly two million people died of exhaustion, starvation and disease. Others, like government soldiers, intellectuals and minorities, were killed and buried at sites that came to be known as “the killing fields.”

Ravin Pan, a math professor and faculty adviser for the Cambodian Student Association, held a viewing party of the film at his house for current and former members of CSA. Pan planned the gathering almost a year before the film was released on Sept. 15. He said that he saw the film as an opportunity for his students to get a better understanding of their Cambodian heritage.

“The generation that went through (the Khmer Rouge takeover) and any generation that goes through war tends to keep it quiet and tries to protect their children from that trauma,” Pan said. “So, in some sense, (“First They Killed My Father”) allows us to look at it again.”

(Story continues below film’s trailer)

Although most of the students in CSA have some prior knowledge about the Khmer Rouge, there are others from Cambodia who never learned about this history in their Cambodian schools. Pan said that censorship of the Khmer Rouge was a result of parents and elders wishing not to speak to their children about it due to the trauma they experienced.

Peter Han, a senior psychology major, watched the film with Pan and his fellow CSA members. He said in an email that the importance of seeing the film was to familiarize himself with the events of the Khmer Rouge in ways that were not previously accessible to him.

“The reason (for the viewing parties) is because not many get to hear how bad the Khmer Rouge really was and parents tend to not talk about this subject due to trauma,” Han said in the email. “So, I believe it is up to the younger generation’s curiosity to have a better understanding of what was going on in Cambodia during that time period.”

In the film, Ung and her family are seen fleeing their home in the capital city of Phnom Penh after it was taken over by Khmer Rouge forces. They eventually end up in one of their camps and forced to do farm labor. Her father, a former military police officer, is taken away months later to supposedly help build a bridge and Ung is trained to become a child soldier.

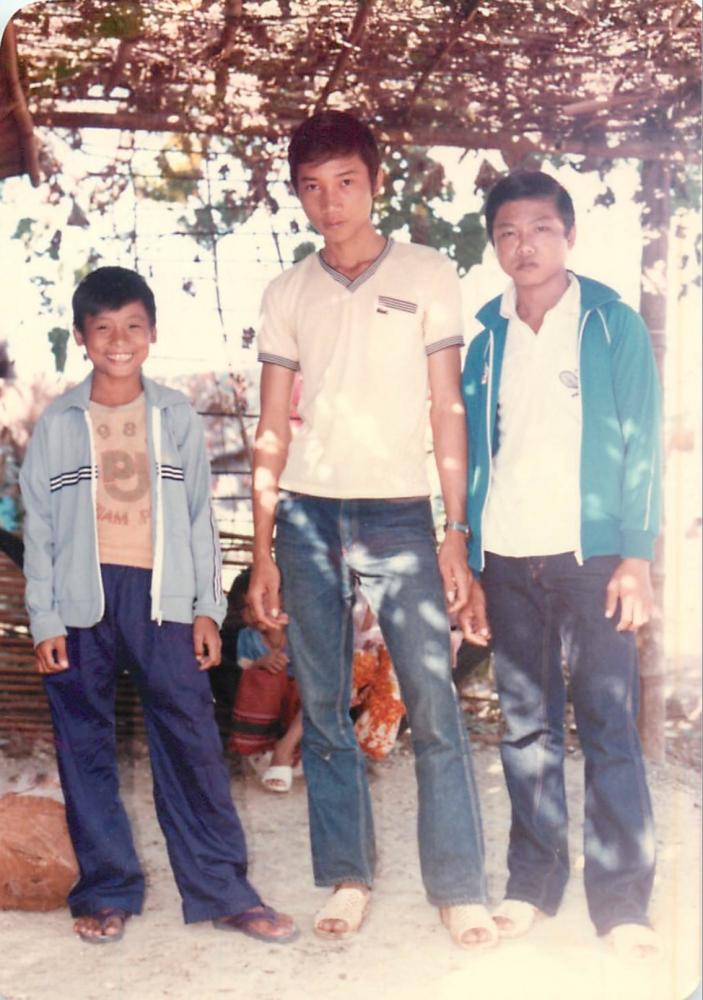

Left to right, Sedah Tath stands with his friend and older brother at the Khao-I-Dang Holding Center in Thailand in 1984. The camp took in many refugees from Cambodia after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Sedah Tath, a math professor and friend of Pan, grew up in Cambodia near the border of Thailand. When he was 8 years old, Tath was forced by Khmer Rouge soldiers to plow fields and dig canals in exchange for food, much like Ung did in the film.

“(The subject) brings me back to the bad times and I told Ravin that I didn’t want to see (the movie),” Tath said. “I did the same manual labor, but more rigorous. I built a canal three meters deep in order to get my ration for the day.”

Although Tath was initially adamant on not seeing the film, he decided to watch it after Pan convinced him to come join him and his students at the viewing party. Pan said that he wanted to create an open space for survivors of the Khmer Rouge.

“This movie allowed us to have a forum to speak about the event that occurred and pushes us to look at ourselves differently,” Pan said. “I hope that it allows Cambodians to come forward and share their experiences in order to heal.”