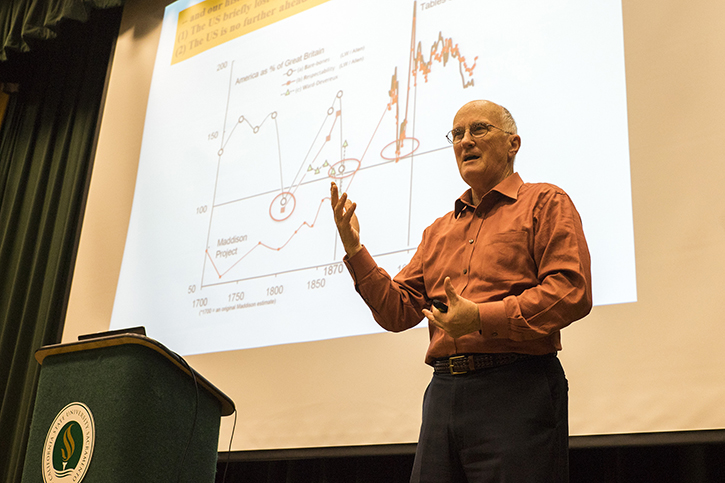

The author of a new book on the history of wealth in the United States spoke at Sacramento State on Monday about how income inequality is increasing and what can be done about it.

Peter Lindert, a professor of economics at U.C. Davis, wrote “Unequal Growth: American Growth and Inequality since 1700” with Harvard economist Jeffrey Williamson.

Lindert said that income inequality between average people and top earners in industrialized countries has been rising since the 1970s, but that the United States has seen a particularly large divergence.

He blamed the trend on weaker labor unions, technological change, increased competition from Asia, increased growth in the number of American workers and slow growth in educational quality.

Lindert suggested four policies that could address the problem based on the data that would both redistribute wealth and spur economic growth, the first being subsidizing paid parental leave for new parents.

“It should be a no-brainer. It’s better for the parents, especially mothers,” Lindert said. “Every country does this for people employed in parts of the economy. There are only two countries that don’t — the United States and Papua New Guinea. We’re kind of weird on that.”

Lindert said that educational quality has stagnated since the 1970s while other countries have been gaining on the U.S.

“The quality of learning in our schools continues to be mediocre,” Lindert said. ”The same is not true in Europe, Japan, East Asia.”

Nevertheless, while he said that preschool subsidies could improve the situation, Lindert pointed out that in elementary and secondary schools “a mass of literature has not shown raising the budget has done anything for the learning process.”

Lindert suggested raising inheritance taxes on the very wealthy. The top rate for the inheritance tax, 40 percent, is only about half the rate taken in taxes from 1936 to 1982.

Lindert pointed out that Andrew Carnegie, the 19th century steel magnet, was against giving young people inherited wealth because it may make them lazy and complacent.

“We’ve been able to find with large data sets that, yeah, that’s true,” Lindert said. “You will retire earlier, take fewer risks and earn less in managing incomes. There’s a slacking effect at the very top.”

The final policy Lindert suggested was tightening regulations on Wall Street banks. He said that while the Dodd-Frank financial regulations passed in 2010 are helpful, they do not address the root of the problem the way that post-Great Depression regulations did.

“In the 1930s, the financial sector so discredited itself that the political swing was all in favor of tightening control of them, and it worked,” Lindert said. “With the Great Recession, we actually came off the Great Recession a bit better. We didn’t come out of the Great Recession as badly as we did in the old 1930s Great Depression. But that’s the problem. ‘Oh it’s not raining, why fix the roof?’ ”

Mason Daniels, the president of the Student Economics Association, said that Lindert was invited because income inequality is such a pertinent issue in today’s political discussion.

“He wrote a book on economic inequality and we felt it was a timely subject for students to be interested in,” Daniels said.

To research “Unequal Growth,” Lindert and Williamson crunched numbers from primary sources to find out how America went from being one of the most economically equal countries in the Western world to being one of the most unequal.

The history of incomes before 1914 is largely unknown because for most of America’s history there was no federal income tax.

Lindert and Williamson made two historical findings that were heretofore unknown.

The average purchasing power of Americans for basic necessities plummeted to below the average purchasing power of Britons only three times — after the Revolutionary War, during the Civil War and from 1932 to 1934, during the Great Depression.

The pair also discovered that the decline of the South’s economy relative to the rest of the nation began not with the Civil War, but decades earlier. The Southern worker’s income is still behind that of the median American.

Gabriel Pond, the vice president of the Student Economics Association, said that he enjoyed the talk because the students who attended were engaged with the material.

“It went really well. Everyone was really engaged,” Pond said.