Undocumented students talk of struggle, search for solutions

November 18, 2014

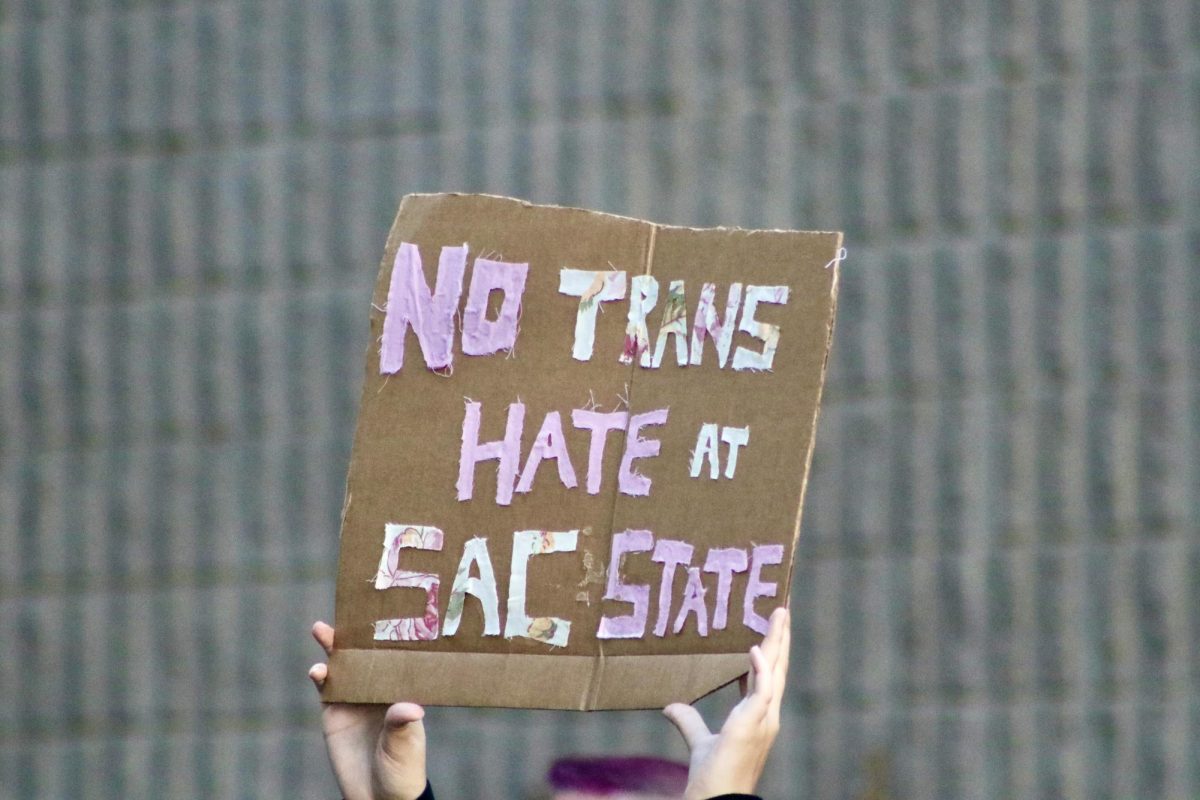

Sacramento State students and alumni and a high school student gathered in The Well to share their experiences with living undocumented in the U.S. as well as their ideas to help other students in the same situation succeed in college.

The nine panelists were brought to the U.S. illegally as children. Several panelists described feeling a desire to excel academically that was challenged by both a lack of knowledge on the college application process and an ineligibility for financial aid.

“I had like the highest GPA. I was involved in ASB. I was involved in sports. I was involved in everything. I did it all because I had that dream of going to college,” speech pathology major Daisy Caro said. Caro came to the U.S. when she was 5 years old.

But by her junior year of high school, Caro said she “gave up” because of the apparent inaccessibility of college.

“I went from this 4.0 student to not even having the energy to copy somebody’s homework,” Caro said.

Caro said her family couldn’t afford to pay for college. Until 2001, the year before she graduated high school, those who had lived illegally in the country since childhood paid out-of-state tuition at California colleges.

In 2001, then Gov. Gray Davis signed AB 540, which allowed undocumented students with a California high school diploma to attend college as in-state students.

Another measure came in 2011 when Gov. Jerry Brown signed the California Dream Act, granting undocumented students access to public financial aid, such as Cal Grants, provided they entered the country before turning 16 and attended California high schools.

The California Dream Act takes its name from a piece of legislation proposed on the national level by Sen. Dick Durbin and Orrin Hatch in 2001 and reintroduced unsuccessfully various times since then.

Sociology major Diana Diaz, who came to the U.S. at 9, also said she had wanted to attend college early on. But she had trouble when the time came to apply because her parents hadn’t gone to college, so they could do little to guide her. Diaz said that left only her peers and teachers as advisers.

“I feel like I couldn’t go to my peers or teachers because they didn’t understand my situation because I was undocumented,” Diaz said.

Diaz said being undocumented and not being able to do things like get a driver’s license “really wore on [her] self-esteem.”

In response to a failed attempt to pass the Dream Act, in 2012 the Obama administration authored Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, also known as DACA, which defers for two years deportation proceedings for some people who came to the U.S. illegally as children.

California legislation followed, allowing those eligible for DACA to apply for California driver’s licenses.

Despite this temporary reprieve, Diaz said she and others remain in a legal limbo, what she said some call being “DACAmented.”

“We’re in the middle ground. We’re not documented. We’re not citizens. We don’t have all the rights that American citizens have, so it scares me,” Diaz said.

Several panelists called for financial aid staff to be better trained to advise students on the California Dream Act. They also wanted a Dream Center where undocumented students could find support.

Andrea Salas, executive vice president of ASI, said the student government is working on creating the center.

Ed Mills, interim vice president of student affairs, and Thuy Nguyen, coordinator of the Dream Act at the Sac State financial aid office, asked students affected by the Dream Act to contact them with questions or concerns.