Head injuries a concern

Kasey Cox received too many head injuries, ultimately ending his soccer career in just his sophomore year at Sac State.

September 19, 2012

A brain-jarring hit after colliding with an opponent leaves an athlete dazed, but the coaching and training staffs are left unaware so the player toughs it out and continues on.

“I woke up (the next day) and felt dizzy,” said former Sacramento State soccer player Kasey Cox. “I felt sick and I couldn’t concentrate, but I didn’t tell anyone because I wanted to play.”

Cox was able to hide his condition for another match but after taking an elbow to the face he knew there was something seriously wrong when his symptoms escalated.

Cox was a sophomore defender for the Sac State men’s soccer team in 2011 when he endured the mild traumatic brain injury, or MTBI, that forced him to stay in bed for three weeks and eventually retire from a sport he had played since the age of 5.

The concussion was the fifth Cox had suffered since he was 9 years old.

Cox’s case is not unique. He is just one of more than 1.6 million people who report cases of concussion caused from organized and recreational sports every year. Sac State’s athletic trainers and coaches from various sports have been trying to combat MTBIs involving Hornet athletes through awareness education and proper care.

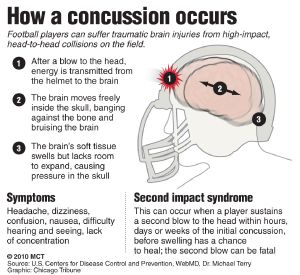

Concussions are caused by any impact to the head or body that renders the protective fluid in the skull useless, allowing the brain to crash against the skull resulting in a mild traumatic brain injury followed by post-concussion syndrome.

Many MTBIs can be prevented through reinforcing the proper use of equipment and technique.

Head football coach Marshall Sperbeck emphasized having his team practice proper form as well as maximizing equipment function.

“The players can do a couple of things daily,” Sperbeck said. “They can make sure that they have proper air in their helmets, tight chin straps and make sure they are using a mouth piece.”

Sac State athletic trainer Heather Farwig said university athletics have been on the forefront of this issue even before it gained massive national attention due to deaths of former NFL players such as Dave Duerson and Junior Seau.

At the start of each season, regardless of the sport, Hornet athletes are required to watch a safety film informing them of the signs, symptoms and dangers of concussions and other traumatic brain injuries.

As a part of Sac State protocol and NCAA guidelines each athlete is given a baseline cognitive test used as a control when concussions are suspected throughout the season.

“We provide a lot of information out there for our student athletes,” Farwig said. “The NCAA is great about providing posters and videos as well as suggestions on how to create an appropriate concussion protocol for an athletic program.”

There has been a collaborative effort between coaching staffs and athletic trainers to keep athletes safe even if it means removing a player from the game.

“I don’t make decisions about when a kid gets back on the field,” Sac State men’s head soccer coach Mike Linenberger said. “I go solely on what the medical staff says and I support the doctors and trainers 100 percent.”

Post-concussion symptoms could last for as little as a week or for more than a year. These symptoms include headache, dizziness, fatigue, noise and light sensitivity.

Allowing an athlete to return to action before the symptoms have subsided could result in a little-known condition called Second Impact Syndrome which may alter an athlete’s life or – even worse – end it.

“Sports have been my whole life so I obviously want to play,” said Cox. “Just thinking about the fact that I could possibly be brain damaged or I could even die from (concussions) outweighed playing sports.”

With concussions not always being easy to spot for the coaching and training staffs, some of the responsibility has to lay with the players to report symptoms.

It is not uncommon for players to hide injuries and to fail to report medical issues to trainers at all levels of competition, but some coaches are seeing changes in mentality concerning concussion.

“With the amount of media attention concussions are getting now, especially at the professional levels, our players are more honest,” said Linenberger. “They are concerned about their health and long-term well-being.”

An athlete being forthcoming is an indicator the education and open dialogue between the NCAA, coaches, trainers and players is having a positive impact.

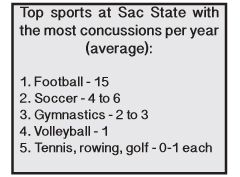

Unfortunately, concussions are the nature of some athletics no matter if it is football, soccer or gymnastics.

Cox will never be able to play soccer at a competitive level for the rest of his life and he said he feels there were things he could have done to prevent his situation and maybe rules could be changed to prevent others from suffering the same fate.

“I would say that after a player has a substantial concussion it should be mandatory for the player to wear a mouthpiece,” said Cox. “However, it is the players’ responsibility to report the concussions.”

Joe Davis can be reached at [email protected].