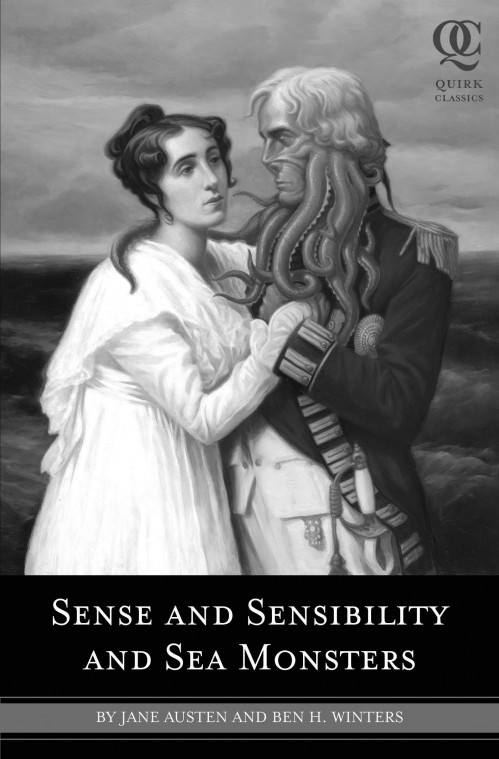

Sea monsters help to enliven Austen classic

October 21, 2009

The topic of love is complicated enough and yet author Ben H. Winters manages to further the complexity by including sea monsters in his novel, “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters.”

In Jane Austen’s original classic, “Sense and Sensibility,” the characters live in the Victorian-era, which was also the time period in which Austen lived. In the novel Austen explores the stress of young love affairs. In Winters creation of the novel, he merely amplifies the issues of love by including a cast of sea monsters – all the while, maintaining Austen’s original characters and plot.

Winters adds Austen’s plot by heightening all absurdities in love and the process of falling in love. Austen develops a slight humor aimed toward young love in which she portrays it’s silliness and minute importance to the rest of the world. Winters cements this idea by inflating the silliness of love to blasphemy.

The importance of financial stability in marriage in one aspect of love that is especially targeted. In Austen’s original work, marrying into a wealthy family is constantly considered by the single characters, but it is Winters who takes this concept to a whole new level with his additional characters.

In “Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters,” a character named Lucy is a sea witch who disguises herself as a human. Lucy marries a young man in the novel and conceals her true identity. On the night of their marriage, Lucy kills her new husband and sucks the bone marrow out of each of his limbs in order to maintain mortality.

I easily caught the selfish similarity between marrying for money and marrying for bone marrow and I applaud Winters for uncovering these absurdities in such a creative way.

It seemed that within every dramatic scene in the novel, Winters included an intrusive sea monster to liven up the plot. The fact that the characters ignored these sea monster disturbances definitely made me chuckle.

I believe that Winters creates this indifference toward sea monsters in the characters not because they are comfortable with the attacks, but because he is poking fun at the cordiality of the times. Appropriateness above all else is the overwhelming tone in Austen’s writings, and it is something that Winters seems to find comical, as do I.

At one point in the novel, the “Devonshire Fang-Best,” a two-headed serpent, attacks two young women while they are competitively discussing a man whom they both adore. The conversation continues throughout the attack, even after one girl is knocked from the boat and surrounded by the beast.

Main characters, Elinor and Marianne, endure similar attacks daily. They are constantly being preyed upon by estranged lobsters and oversized tuna. The girls find these pesky sea-beasts to be the least of their worries. Instead, they fret day after day about their current love affairs and why men haven’t come “to call” yet.

Many readers may find Austen’s writing style confusing because of the time period in which the text was written. Although, Winters writes very similarly to Austen, somehow his extra content is more easily read and comprehended.

For example, Winters wrote, “(Elinor was) grateful to have the monster attack as an excuse for her reticence.”

I like how Winters belittles the vicious monster attack. He does so by utilizing Austen’s cordial style of writing.

All in all, Winters does an excellent job of molding Austen’s traditional plot with unusual circumstances, while using a tongue-in-cheek as a catalyst for this dynamic combination.

Katrina Tupper can be reached at [email protected]

Check out the Q&A with author, Ben H. Winters