U. Penn researchers test HIV therapy in humans

December 4, 2006

PHILADELPHIA – University of Pennsylvania researchers say the future of AIDS treatment, and perhaps the treatment of other diseases, could lie in giving sick patients doses of a genetically modified HIV virus.

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, attacks T-cells which are white blood cells that are critical to the immune system.

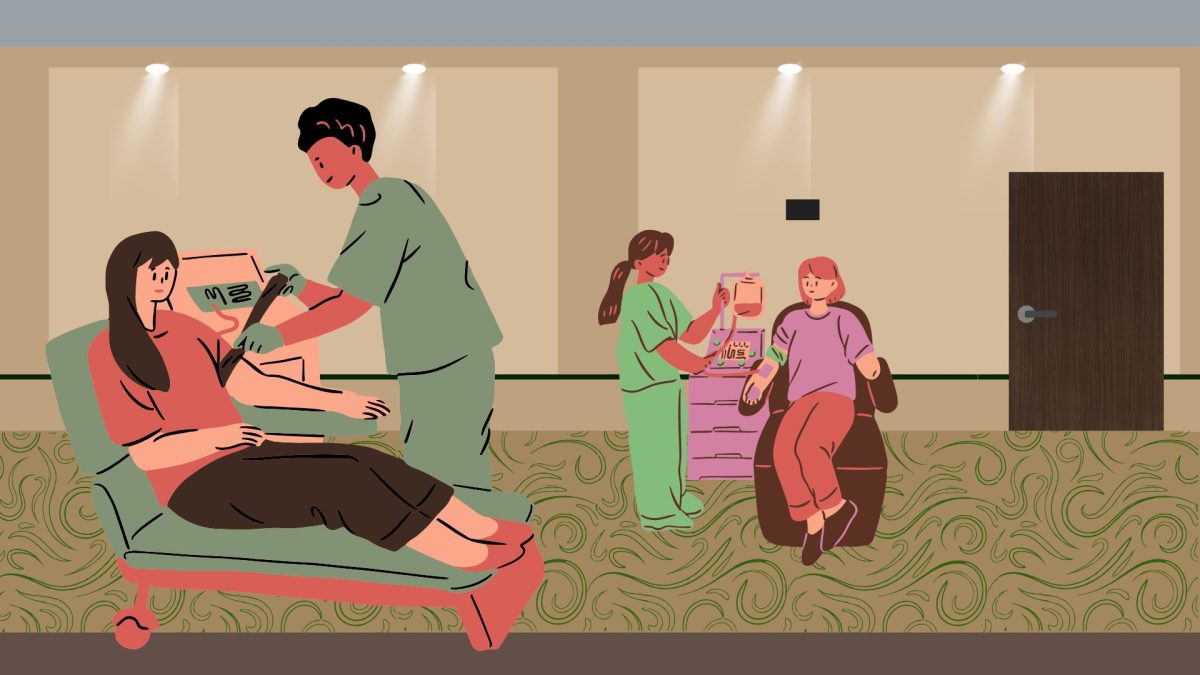

In the first in-human trial ever, Bruce Levine and Carl June of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, along with Penn Medicine professor Rob Roy MacGregor, took T-cells from HIV patients and inserted a modified virus back into them.

Levine described the engineered virus as “wearing the enemy’s uniform.”

“The use of HIV itself … has never been done before,” he said.

The trio recently published the results of the first phase of their study, in which they observed the effects of a single injection.

“The modified virus tricks its way into our cells,” MacGregor said.

The results were astounding. June said patient’s T-cell levels not only stopped dropping but also dramatically increased in some patients.

The primary objective of the study was to determine the “safety and feasibility” of the procedure, Levine said.

There are high risks associated with such treatment, June said, including leukemia and the possibility of the virus mutating and making the patient sicker.

MacGregor said the five patients that participated in the study had advanced HIV that had failed to respond to other therapy.

They were, in a sense, “backed into a corner,” MacGregor said, with nowhere else to turn.

“It’s an altruistic cohort of people,” Levine said.

It took years for June and Levine to get approval for their study, especially after the death of 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger from complications of a separate gene-therapy study conducted at Penn in 1999.

The field of gene therapy underwent “intense scrutiny” as a result, June said. He added that, while “appropriate,” it put them “on hold for about two years.”

If the studies continue to prove safe and effective, the question becomes whether this can be a treatment for the larger HIV-infected population.

“We would have to treat the process as a drug,” Levine said. He added that the treatment is not as simple as taking a pill because “everyone’s immune system is different.”

MacGregor and Levine said modified-virus insertion could become a viable treatment option for HIV patients within 10 years.

Additionally, June said, other Penn researchers are interested in how this therapy could be used for certain kinds of cancers, as well as disorders such as sickle-cell anemia.