Hearts in Atlantis and Bully

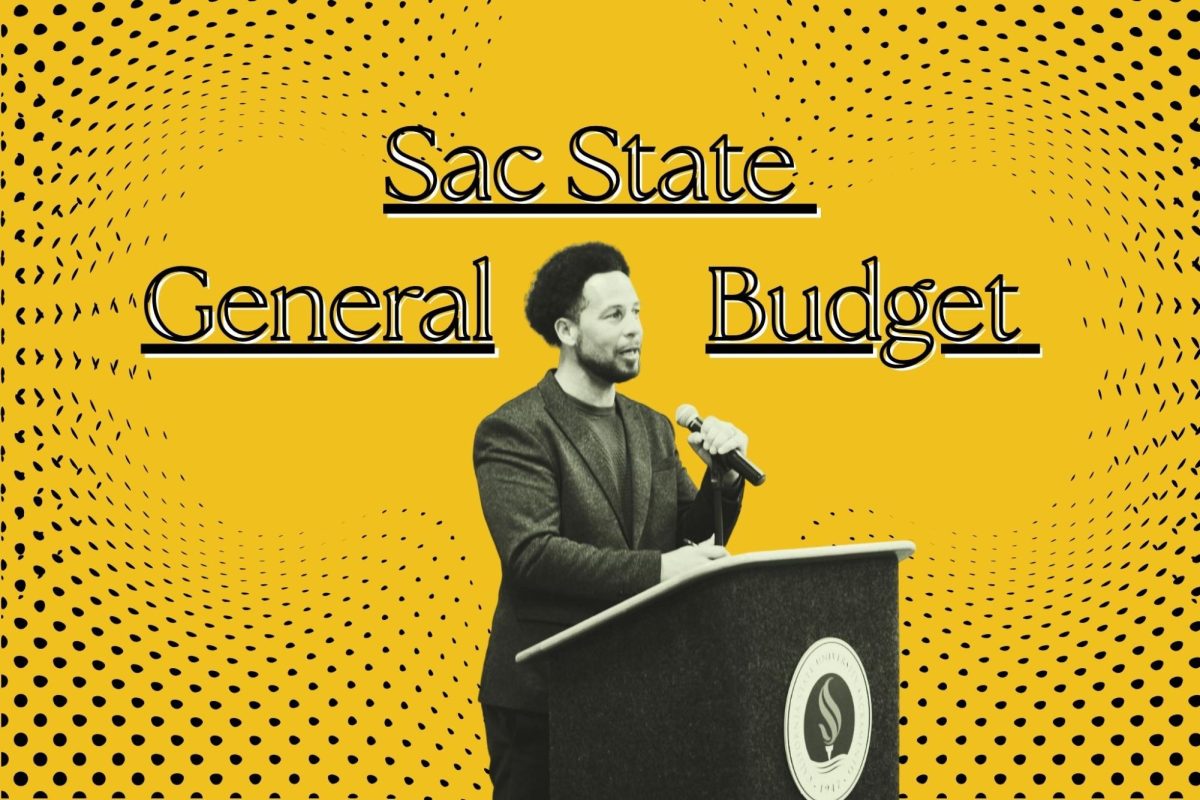

Image: Hearts in Atlantis and Bully:Anton Yelchin and Anthony Hopkins star in “Hearts in Atlantis.” :

October 15, 2001

Hearts in Atlantis

Hollywood movies took a back seat to everything following last month?s devastating attacks on America. With all the various political perspectives storming in on the American psyche, there seems to be little room for going to the movies. For anyone who has forgotten what was so good about living in America (or in this world for that matter) try “Hearts in Atlantis,” not as an escape, but as a reminder.

“Hearts in Atlantis” (based on the Stephen King novel) tells the story of a boy, Bobby Garfield (Anton Yelchin), the neglected only child of an overworked single mother. She wants the best for her son, but is just too preoccupied with her secretarial duties. Bobby passes the time hanging around his small town with his best friends, Carol and Sully. When his mother rents the upstairs room to an older man named Ted Brautigan (Anthony Hopkins), Bobboy develops an instant friendship with the man.

Ted hires Bobby to read the paper to him every afternoon. Bobby wants the money for a Bike, and Ted knows this. “How did you know I wanted a bike?” Bobby asks. “All boys want bikes,” Ted responds.

Bobby soon discovers that there is something mysterious about Ted. For instance, he suffers from strange spells, speaking to himself with eyes gazing upward. He also tells Bobby to keep on the look-out for men with dark suits which he calls “Low Men,” who leave coded messages in lost pet ads placed on telephone posts. Bobby learns that the “Low Men” are looking for him, and that Ted will have to leave when they draw closer.

“Hearts in Atlantis” is directed by Scott Hicks, who also directed “Shine” and “Snow Falling on Cedars,” two high-quality films in their own rights. With help from cinematographer Piotr Sobocinski, Hicks has captured images that read like nostalgic poetry. Childhood is so sacred that few films succeed in capturing its essence, but “Hearts in Atlantis” comes close.

Three and a half stars out of four

Bully Jason Okamoto

State Hornet

On his third try, photographer-turned-director Larry Clark has gotten it right. His latest film, “Bully,” takes the so-called “objective cinema” that his 1995 film “Kids” was based on, and creates a cinema of consumption. While “Kids” tried to shock us with images of inner-city abandoned youth, “Bully” gives us a 360 degree view of American youth.

“Bully” is based on a true story about two best friends, Marty Puccio (Brad Renfro) and Bobby Kent (Nick Stahl). Ever since Marty could remember, Bobby has bullied him around. They both have the same job, and Marty depends on Bobby for rides around their hometown, Hollywood, Florida. Bobby is pretty close to pure evil. From the get-go it is easy to tell that Bobby is an abusive individual who thinks he is invincible. He abuses Marty verbally and physically to the point where Marty begs his parents to move. Labeling him a “Bully” is a compliment — he is closer to the spawn of Satan.

Marty, like most teens his age, feels isolated from his parents and the world. Things start to change when Lisa Connelly (Rachel Miner) becomes his girlfriend. The only thing that seems to get worse is Bobby’s violent grip over his life. After Bobby rapes Lisa and her best friend Ali (Bijou Phillips), it is decided that he must die. “He is the source of everyone’s problems,” Lisa says. Marty can’t help but buy into his girlfriend’s vision of “a better life,” or, in other words, “a life without Bobby.”

Lisa and Ali jump into action by pulling together a rag-tag group of teens, made up of various friends and a hitman to murder the bully. It is clear that all these teens are interested in is sex, drugs and more sex. Their plot to kill Bobby does not bring these interests to a halt, but runs parallel with them.

Larry Clark shows us the truth about the kids living in ‘Purgatoryville,’ who have nothing better to do than kill “the problem.” These kids are driven by nature and don’t acknowledge that they are members of a bigger society. This gives them free will to do what they please, without thinking about the consequences that will eat them up the next day.

Despite how hard “Bully” may be to stomach, it is a socially important cinematic gem. Clark moves beyond documentary-style photography and throws in shots inspired by old Hollywood films. The lighting is poor, and isn’t always in focus. This contributes to Clark’s staging of realism, which is both fascinating and effective. The film is not rated due to the extreme rawness of the kid’s lives (some have labeled it soft-core porn). By showing everything, Clark is able to make a confident statement rather than ask a contrived question. That statement: “If these kids have a conscience, then you definitely do.”

Four stars out of four