Ditching cellphones for life off the grid

October 15, 2014

With a cellphone seemingly glued to every ear, eye socket and pant pocket, more than 28,000 cellphones and their owners roam campus this semester.

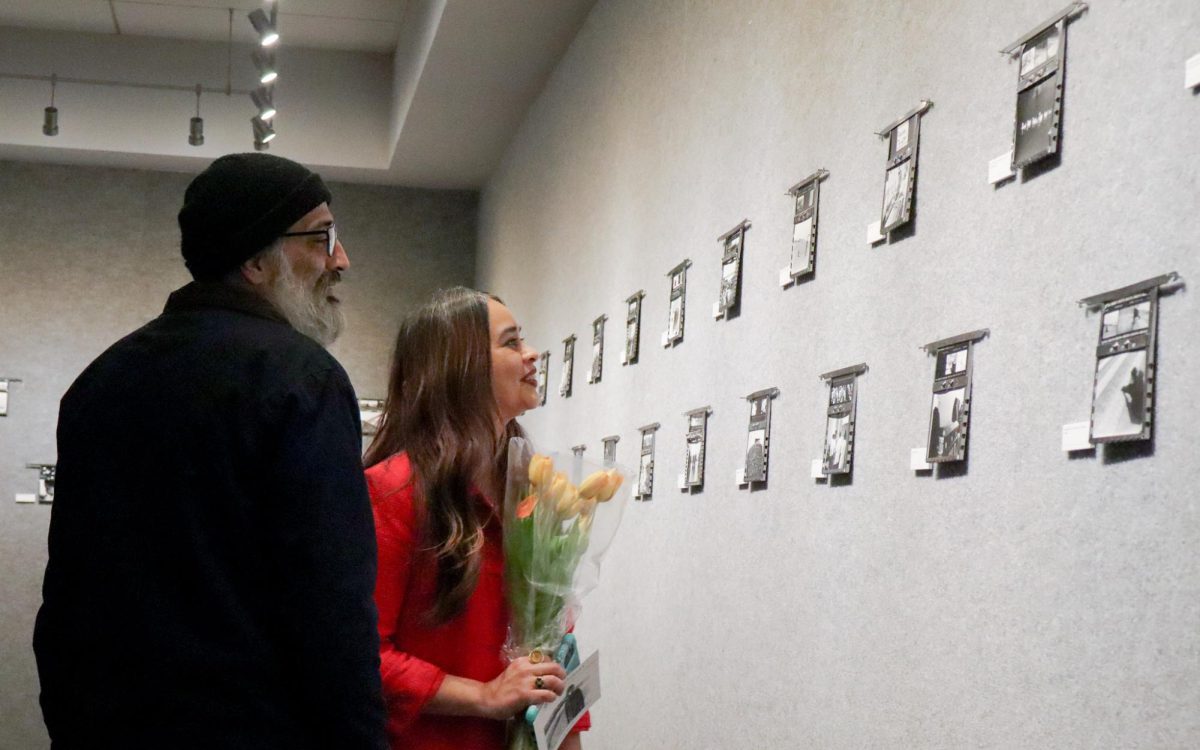

But there is one cell phone conspicuously missing on campus: Chris Maben’s.

Maben is a communication studies professor at Sacramento State that has ditched the cellphone phenomenon.

He said each semester he tries to introduce himself in a new, memorable way to his classes, and the “no cellphone” statement is the one students have the hardest time believing.

“They wonder, ‘How is it that I survive?’” Maben laughed.

Maben said he never considered himself the rebellious type, but in high school he did not see the need to feed into the cellphone trend.

“I thought, ‘I don’t have to be like you,’” Maben shrugged. “‘I’m not going to have a cellphone’”

When he graduated college, Maben landed a job that required traveling up and down California. The company he worked for gave him a free cellphone to keep in contact, but he paid for the phone in a different way.

“I hated it,” Maben said. “They could always get ahold of me.”

Maben said he values his private time and being available around the clock was too much.

Although he firmly believes a cellphone is a needless, added expense in life, he does admit that sometimes it would be nice to have one.

“I always understand the good aspects [of a phone],” he said.

Twice in the 18 years since receiving his driver’s license, his car has broken down on the side of the road. One of those times was on a country road at night. Two other people in the car had cellphones but one was dead, and the other did not have reception.

“So we walked,” Maben said casually.

His rationale remains the same: paying $100 per month for a cellphone that he needed twice in 18 years pays for two new cars.

He does admit his wife, friends and family “hate” that he refuses to own a cellphone, but he did break down and get a pre-paid phone when his wife was in the later stages of her pregnancy.

“But now that we have a healthy baby girl, I don’t have a cellphone again, ” Maben said.

Students, on the other hand, have a harder time letting go.

Rebecca Pantoja, a junior Spanish major, said she has never left her phone at home, and even packs a charger in the car and in her purse to resuscitate it when it dies.

“I can leave my homework—anything else [at home],” Pantoja said. “But not my phone.”

Sophomore math major Patrick Chen feels the same attachment with his iPhone.

“I had a nervous moment,” Chen explains when his cell phone died. “It’s like a mini heart attack.”

But feelings like this are not uncommon.

Maben cited New York Times article “You love your iPhone. Literally.”

The article explains that dopamine levels in our brains skyrocket when we use our cellphones.

In the article, 16 subjects between the ages of 18 and 25 were exposed to audio and video of ringing and vibrating iPhones.

The test found each subject’s brain lit up when hearing and seeing the phone go off just as it would if a girlfriend, boyfriend or family member was near.

The phantom vibrations, shakes and nausea people sometimes experience when leaving their cellphone at home are all very real feelings.

“It’s very scary to detach yourself from technology,” Maben said. “But that doesn’t mean you can’t do it.”

Going off the grid completely, like Maben, may be difficult for students, but taking one day, or even a couple of hours to just unplug can allot for some truly private time hard to come by in an age where we are always available.