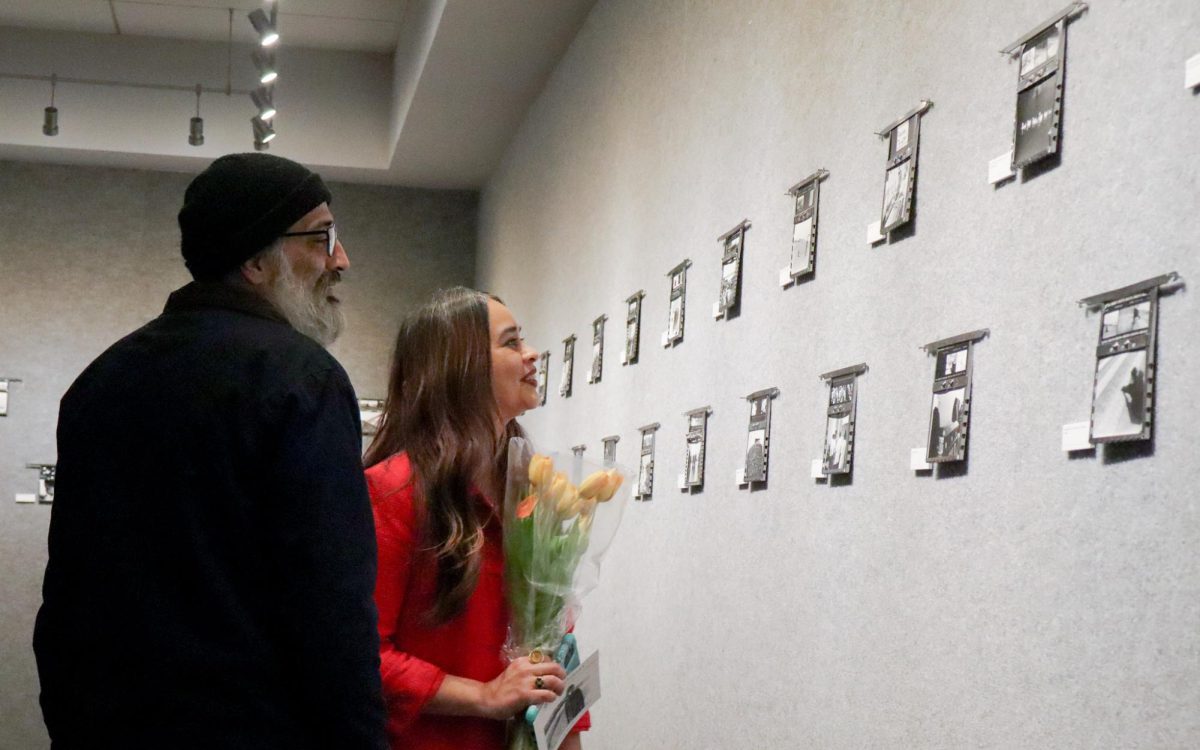

Death penalty subject of Sac State art exhibit

Malaquias Montoya stands by his interpretation of an execution.

October 19, 2011

Malaquias Montoya, an artist who created controversial works surrounding the debate on capital punishment, opened his exhibit in the Sacramento State Library Gallery Annex Thursday.

The exhibit, “Pre-Meditated: Meditations on Capital Punishment,” opened with a reception that included guest speaker Mike Farrell, president of the local chapter of Death Penalty Focus. He is best known for his role as B.J. Hunnicutt in the television series, M*A*S*H.

Montoya has been making posters against the death penalty since 1976 when he watched the trial of George Jackson, an American convict killed three days before trial. Capital punishment had always been a subject of importance to him, but he did not know much about it.

“I am not a scholar on the subject by any stretch of the imagination,” Montoya said. “Something happened when I was young. My father was abusive and I hated him. But my mother told me, ‘Your father was born a child just like you, but he grew up and something made him go bad.'”

After that, Montoya grew compassionate and understanding of his father.

“And then I started to dislike the things that made him ugly, not him. And that’s when I started thinking politically,” Montoya said.

In 2000, when it seemed executions were happening monthly in Texas, Montoya thought of having a show on the subject.

“I put the work together and opened it in Notre Dame, which is a Catholic University. There were a lot of comments, and it led to an interesting debate,” Montoya said. “It then moved to Duke University, Chicago, Los Angeles, the Nelson Gallery in Davis.”

There are silk screened series of lynchings, paintings of the first woman executed, penalizing of the innocent and excerpts and depictions of court cases involving mentally retarded prisoners.

“The killing of the mentally retarded was hard to believe,” Montoya said. “One man had his last supper and saved his piece of cake. When the guard asked him if he wanted to eat it, the prisoner answered he wanted to save it for when he got back. He had no idea what was happening.”

According to a study done on inmates by the Human Rights Watch, America has more mentally ill in jail than in hospitals.

“It makes me feel anger, horror, pity, and rage at the people that continue to insist this is a civilized solution while blinding themselves to this ugly reality,” Farrell said. “I think it’s obvious why it’s wrong, but Malaquias depicts it in a more nightmarish sense.”

Farrell said one of the things he admired most about Montoya’s work was that it showed there was no humane way to impose the death penalty.

“It’s brutal, and it really portrays that there is no humane way to take a life,” Farrell said.

On the wall opposite the entrance, there is a plaque that reads, “For there to be an equivalence, the death penalty would have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim in advance of the fate at which he would inflict a horrible death on him, and who, from that moment onward, had confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster does not exist in private life.”

Farrell said he is often accused of only caring about the murderer. He said everyone is affected or injured when violent crime occurs, and believes part of the $180 million that America has spent so far on the death penalty should be put towards dealing with the results of that act.

“What about life in prison without the possibility of parole?” asked Farrell Thursday.

He said the perpetrator should be required to work and the money they would be compensated should be donated to a victim relief fund.

“I support the nonviolent message and nonviolent protest. I’m against capital punishment,” said Jason Youngkin, a second-year grad student majoring in teaching. “I’m an artist as well, and this imagery is moving and powerful.”

At one of his shows, Montoya said he saw a man looking at one of his paintings, crying. He did not walk up to him and ask him why, and decided to give him his space. After the show, the man walked up to Montoya and gave him a big hug.

“He was in jail, and one day, another prisoner patted him on the back, which meant he wanted to give him something,” Montoya said. “The man reached behind him and pocketed the piece of paper, forgetting about it. Later that night when he remembered, he took it out and looked at it. It was one of my paintings.”

It was being passed around to the inmates, Montoya said.

“You always wonder when you do 500 posters, is this going to do any good? Is this going anywhere?” Montoya asked.

Farrell said Montoya uses his talent to ask important questions of society.

“The questions that need to be asked,” Montoya said. “The fundamental right to life is often abused.”

Kaitlin Bruce can be reached at [email protected]