Studying Abroad: The perils of travel

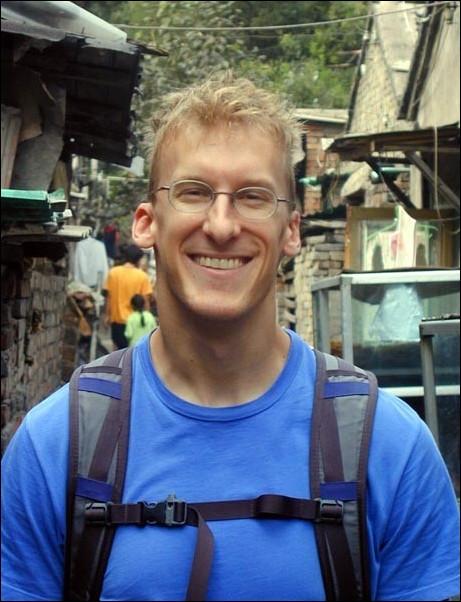

Image: Studying Abroad: Why China?:David Pinck is pursuing his graduate degree in Criminal Justice through Sacramento State while studying abroad in Beijing, China. Photo courtesy of David Pinck:

October 14, 2005

Editor’s note: David Pinck is currently a Sac State graduate student in Criminal Justice, and has been since Spring 2004. He is studying Mandarin and Chinese culture at Beijing University for one year, and is conducting research for his thesis which concerns the Chinese Police system.

He grew up in Tracy, Calif., and earned his Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo.

Studying abroad presents many challenges and many dangers, the greatest of which is not immediately apparent to the unsuspecting student.

Before coming to China you can bet I did my research. If a possible threat existed, I preempted it in a heartbeat. For example, I befriended the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention like no other before me. Typhoid, polio, encephalitis ?” you name it, and I’ve been immunized against it. Never having been one to collect comics or baseball cards, I filled my childhood void by taking to epidemiology like a fish to water.

I learned what parts of the body various diseases attack, when and where they were discovered, and how the vaccines operated. I gleefully welcomed shot after shot after shot, knowing that with each prick of the needle there accompanied an increased probability of my own survival. My body, if I had anything to do with it, would become not just any temple ?” but the Fort Knox of the biological kingdom.

China’s social and political threats were just as fascinating to me as were its diseases (although, to be quite clear, I find nothing pathological about the culture here). For example, it’s intriguing to me that nothing makes for a better conversation stopper than casually throwing in mention of God over polite dinner banter. I made this particular mistake just the other day and got back only silence in return, which, oftentimes, is far worse than open ridicule here.

It would be easy to presume that China’s noticeable dearth of religious zealotry ?” markedly, its thankful absence of blow horn proselytism ?” might imply a tendency towards atheism. Not so. The people here are deeply spiritual, it’s just that, wonder of wonders, they don’t feel obliged to force their beliefs onto other people, as is the devout custom in the United States. This, incidentally, was a good thing to discover before coming here, because had I fallen prey to my compulsion to import a suitcase full of bibles, I’d have been deported faster than you can say “Mary Magdalene.”

China’s greatest hazard to someone in my situation, as it turns out, concerns neither epidemiology nor social etiquette. With its remarkably low violent crime rate toward foreigners, neither is crime. It is interesting to note that, as I figure it, my greatest danger while abroad is also your greatest danger while domestic.

It’s far too simplistic to assume that personal injury, deportation, or theft could be your greatest threat while studying in another country. This, at least in the larger scheme, is certainly not the case- here in China, or anywhere for that matter. The greatest danger that can arise while abroad casts you not as the victim, but as the culprit instead.

You, as an American expatriate, wield incredible power over the perceptions of everyone around you. You may not think it, but the moment you cross the border onto foreign soil you become an ambassador, a diplomat. Your actions forge policy in ways you could not possibly comprehend. Your utterances have long-lasting effects, your words will be remembered long after you are gone.

What you volunteer about your own culture is, for this reason, just as important as what you choose not to volunteer. You can choose to create, perpetuate, or destroy any myth you desire. You can surf, if you so choose, your unfounded notoriety into a social niche that finds you the Ferris Bueller and everyone else your foil. You can act the part of The Ugly American and propagate prejudice, distrust, and even hatred in the process.

The way you carry yourself, the way you handle the situations that arise around you, will become anecdotes. Told and retold, people far removed from you will come to think of themselves as having been there themselves to witness your barbaric temper, or your refined courtesy. At the grocery store, on the street corner ?” everywhere you go, people will study you. They will try, as humans so often do, to discover some pattern to your behavior, some algorithm behind your very nature. If, by chance, you happen to be a jerk, then all the worse for every American after you, because first impressions do make a difference.

I have lived this unfortunate reality. On many occasions I have found myself in the wake of some peanut-brained individual trying to prove my worth, trying to untie the knot of distrust or to unfurl the ligament of disrespect they so casually wove. Sometimes I don’t even get this chance. I have on many occasions found myself despised for no apparent reason, detested before even introduced.

The people affected by your actions, it should be remembered, will have children. Their children will have children. Before you know it, your discourtesy, your arrogance as a mindless foreigner, has shaped in some way the development of generations of people. You have promulgated misunderstanding and, quite possibly, negated the efforts of generations of educators. This is the greatest threat to anyone studying abroad, and it just so happens to remain as important a threat to you right there in California, too.

Remember, choose your words wisely.