‘People being killed left and right’: Ukrainian student’s social media fills with troubling scenes from home

Esti Kovalchuk, a business admin major at Sac State, takes a break from her studies to enjoy a moment in the sun in front of the library on Monday, April 11, 2022. After leaving the country four years ago, Kovalchuk said the news of recent Russian attacks on Ukraine have been scary to witness second-hand.

April 28, 2022

It was just after 5 a.m. in Ukraine when the Russian army launched its first attacks on the country on Feb. 24, 2022.

Business Administration major Esti Kovalchuk, who has only been in the U.S. for four years, said her first glimpse of the news came to her through a post on Instagram from a friend in Ukraine who was awakened by the attacks.

“I remember I was sitting in my [human resources] class,” Kovalchuk said. “The entire country was asleep when they started attacking. [My friend] woke up from flying planes and sounds of explosions. She’s like, ‘this is scary.’”

The sounds of air raid sirens blared from her phone as the hours passed and more of her friends began checking in on Instagram. It was a sound that Kovalchuk said she’d only heard in war movies. As her friends traversed down streets where Kovalchuk had lived and studied, the harsh wailing warned them to seek shelter.

“The reality [for] a lot of my friends is that they are spending a lot of their time in bomb shelters– like almost like every day,” Kovalchuk said. “In my memory, especially my hometown, it’s a very beautiful city. It has Austrian architecture. Now they’ve built all kinds of protective shields over the historic buildings.”

Kovalchuk lived in Ukraine until she was 17; although her father is Ukrainian, her mother is Dutch, which puts various members of her family all over the globe. On her father’s side, she has an aunt in Russia and an uncle still living in Ukraine.

“I come from my city called Lviv; It’s one of the most western in Ukraine,” she said. “There were some bombings near the city. Somebody I used to go to summer youth camp with is from Lviv. They fired on a military station. She was in another building, but her dad died in that bombing.”

Kovalchuk emphasized that it is difficult to comprehend the fact that horrific bombings were happening at the exact time she was speaking at her outdoor table at Scorpio Coffee in Sacramento.

“It’s really hard to understand this war,” Kovalchuk said. “We’re sitting in the sun and it feels normal. I cannot imagine 100% still that there’s war in Ukraine. It’s gonna take a long time to rebuild it. It’s been pretty horrible.”

Sac State history professor Dr. Aaron Cohen is teaching a class this semester on the fall of communism. He said students in his class from Ukraine and Russia have both quickly expressed disapproval of Russian president Vladimir Putin.

He said that sometimes passive newsreaders can misinterpret the magnitude of an atrocity like the attacks in Ukraine, adding that even those not directly impacted by missiles, displacement, or violence still suffer the effects of the ongoing conflict.

“Most people in Ukraine, of course, are not being bombed every day, but their lives are still being wrecked,” Cohen said. “The economy is wrecked. It’s under martial law, the entire country. They’re obviously experiencing radical changes in their lives, which is often the case with war.”

Kovalchuk said that when her father recently spoke with her aunt — his sister — in Russia, it was obvious that the state media had misled her.

“The things she believes are what their media tells her,” Kovalchuk said. “All those things that in Ukraine are happening she’s like, ‘oh, we don’t talk about it,’ believing that all Ukrainians are Nazis killing people and killing kids. Very strange beliefs to justify.”

Both Cohen and Kovalchuk commented on the strict control Russia wields over its media channels. Cohen said he believes Russia’s control over the information its people can access allows their government an advantage in swaying public opinion.

“Most people [in Russia] basically just accept what the government says and they don’t have access to other sources of information,” Cohen said. “What I’ve been observing is that probably around 70% of people in Russia will say they support this special military operation. It’s so high because people don’t really know what’s going on.”

He suggested that any population of Russians that support the war are likely to change their position if enlightened by more diverse access to sources of information.

“Once more facts get out there, then public opinion starts to erode,” Cohen said. “That’s why they really don’t want alternate facts to get out in Russia. The fact that the Russian government has to control the media so strongly is a sign that they’re afraid that their narrative is ridiculous, which it is.”

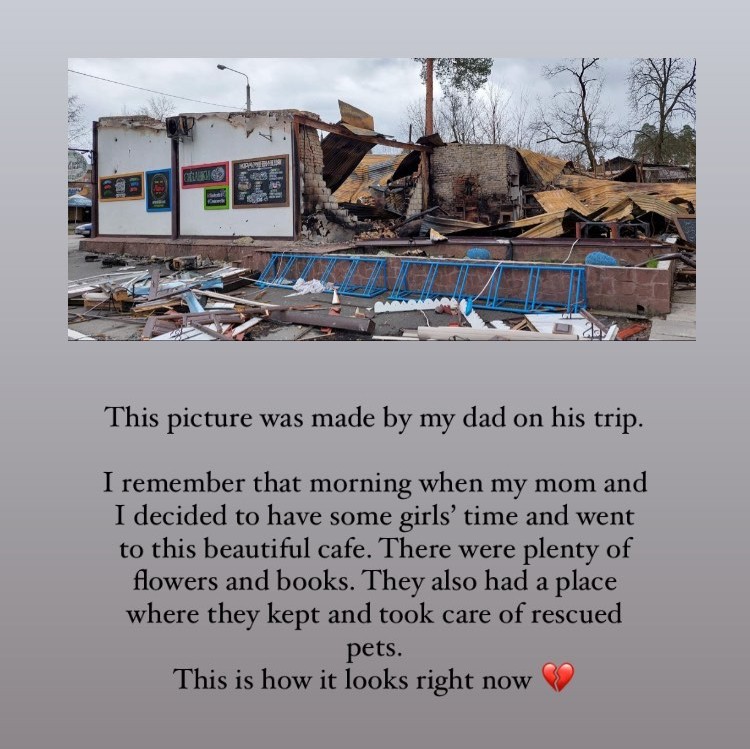

Kovalchuk recalled attacks that broke out where her sister studies in Bucha shortly after Russia’s initial bombings. In areas where Ukrainian forces can maintain or gain a foothold, the aftermath of war is reportedly gruesome.

She recalled that when Ukrainian forces were able to clear Bucha of Russian forces, what they found was horrific. With new pictures of how brutal the attacks have been filling her Instagram feeds, she said it’s been hard to process this new reality in her home country.

“We call it genocide,” Kovalchuk said. “A lot of people dead on the streets; people dead with their hands tied to the back and shot, including dead children. The numbers are so big that they just have to dig a big hole and put all the bodies in; especially in that city.”

In some cases, supply chains have been interrupted by Russian forces. Bombings and shootings in Bucha not only ended innocent lives but transformed a place Kovalchuk thinks back on fondly, according to her.

“I remember walking on those streets,” Kovalchuk said. “It was sunny, birds singing. There’s a beautiful park near a lake. This is how I remember that place. And now, I look at the pictures; it is completely dark, bombed.”

According to Kovalchuk, Russian forces are operating with a total disregard for the war crimes they’re committing. Corridors meant to protect citizens as they evacuate areas under attack have been mined and maternity wards have been bombed.

“They don’t follow codes of the war,” Kovalchuk said. “They’re killing people — killing children.”

Though an end to the attacks would mean her homeland can enjoy peace again, she said she isn’t sure that its people will be safe from future attacks as long as Putin remains in power. For the safety of Ukrainians everywhere and in hopes that Russia can implement more democratic leadership, according to Kovalchuk, Putin’s reign must end.

“Every Ukrainian wishes his death,” Kovalchuk said. “Currently, people have no voice in [Russia]. They do not choose their president. As long as Putin is there, I don’t see it being an easy end in any way.”

Kovalchuk said she hopes to have Ukraine be free and protected in some way.

“It seems like we are the only one that has the power to protect ourselves,” Kovalchuk said. “We are getting some military help from the west, but it’s not as big as we would have hoped.”

Linda davis • Apr 29, 2022 at 1:19 pm

Heartfelt article. Well versed

Eric Davis • Apr 29, 2022 at 1:01 pm

Well written and very insightful Casey!