Moneyball – A review

September 26, 2011

“The first man through the wall, he always bleeds. Always.”

This is what Boston Red Sox owner John Henry tells Billy Beane near the end of “Moneyball,” the best movie I’ve seen in theaters since “True Grit.” Billy, who is always quietly pondering his self-worth, endured more than his fair share of bleeding during 2002.

For Billy (Brad Pitt), the general manager of the Oakland A’s, the wall was made of managers, coaches, scouts, GMs, broadcasters, and fans who were set in their ways and not receptive to his new strategy for building a successful baseball team.

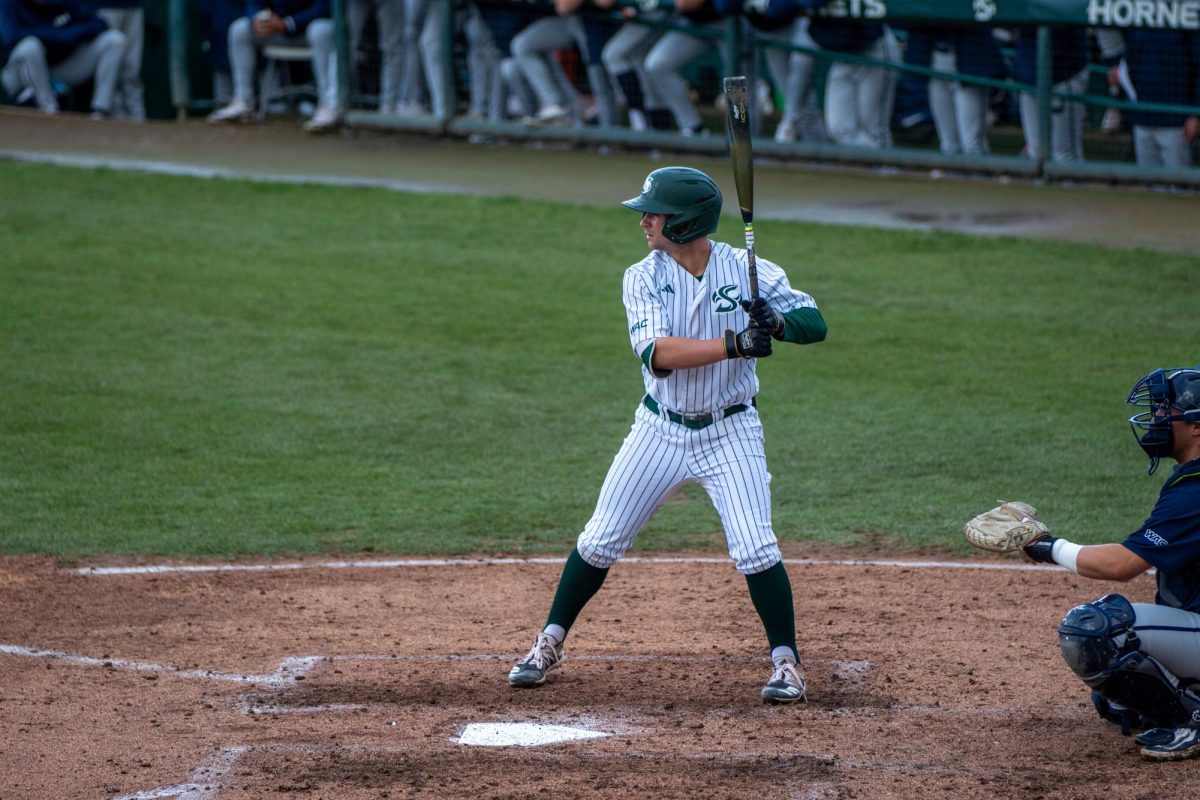

Billy’s plan, thanks in large part to Yale grad Peter Brand (Jonah Hill in his most subdued and effective role), is to get productive but vastly undervalued players by focusing on statistics no one else in baseball values properly. If done successfully, he thinks Oakland’s $41 million payroll can compete with the Yankees’ $126 million.

This leads to the signings of Scott Hatteberg, Jeremy Giambi and David Justice. What do these guys all have in common? They get on base.

Billy doesn’t care how they get on base, so long as they do. Getting on base equals runs, and as Peter Brand’s whiteboard shows us, runs equate to wins.

Director Bennett Miller (Capote) does a great job of appealing to the non-sports fan. Yes, the movie oversimplifies the philosophy Beane and Brand used (the movie makes it seem like they only looked at on-base percentage) but it does so in a perfectly reasonable and effective manner.

The movie successfully sets the tone by educating everyone in the audience, sports fan or not, on the contrasting views of baseball’s new and old schools.

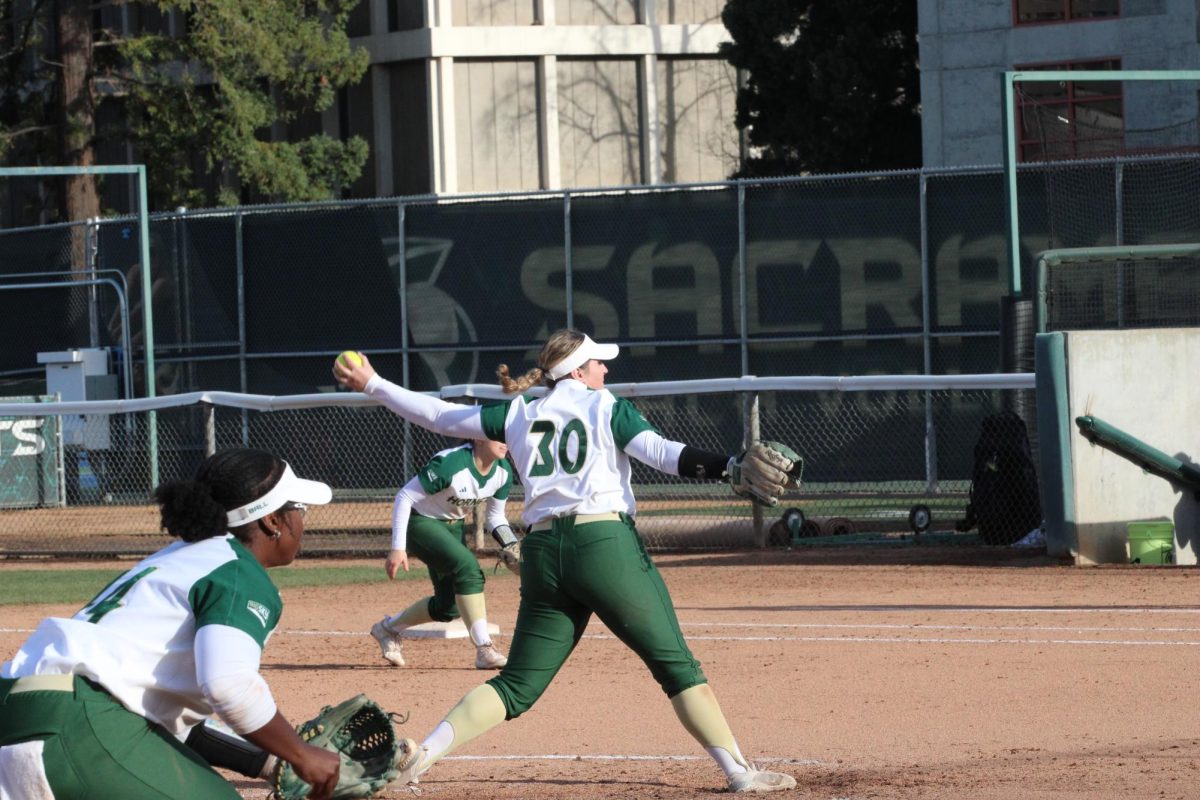

Early in the movie we see Billy sitting in a conference room at a table with about 10 scouts.

The scouts take turns discussing a prospect and his pros and cons. When talking about a player the scouts say things like, “his bat’s got good pop” and “he has a classic swing.”

A couple of scouts go as far to say that a certain player has “a good face,” as if a face can help a player hit to the opposite field.

These old school baseball guys think that they can tell everything there is to know about a player just by looking at him. Beane, Brand and statistics prove they can’t.

The casting of the scouts is pitch-perfect. The youngest of the lot looks to be 60, and the most likable scout wears an oversized hearing aid. When young Peter Brand walks into the room, the scouts know something is up, and it ain’t to their liking.

The purpose of these scenes is to exemplify the type of thinking Billy Beane was up against in the early part of the millenium.

As we learn, Beane was up against this outdated way of evaluating players his entire life.

A first-round draft pick of the New York Mets in 1980, Beane never became a productive big leaguer. Beane was misjudged (and let down) by the same brand of scouts that worked for him in 2002.

Not enough confidence, those scouts might say.

Beane asks Brand if he would have drafted him in the first round. After some coercing, Brand finally admits, “I would have drafted you in the ninth round. No signing bonus.”

It sounds harsh, but this is what Beane’s after – the truth about his place in life.

Beane never gets his championship ring (though he’s still trying), but the movie’s biggest moment is Beane’s biggest affirmation, and the pseudo-climax to this climax-less film. (Make no mistake, this movie is so well done, it’s better off without a Hollywood style ending.)

Beane was the first through the wall, beaten and bloodied. But had he never run through, he’d never have gotten the chance to heal.

Dante Geoffrey can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on Twitter: @dantegeoffrey.