Your donation will support the student journalists of Sacramento State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Former ICE detainee continues activism, credits music for transformative healing

Charles Joseph could face deportation without Gov. Newsom pardon

March 17, 2021

Charles Joseph beams as he looks out past the front yard to the street. He’s sitting outside a family home, in the sun, surrounded by the playful screams of his nieces and nephews.

Today is the day his house arrest order has been lifted. After 10 and a half months of confinement, Joseph can finally walk across the street.

“I usually walk to the edge of the sidewalk and look across the street, “ Joseph said. “It’s been 14 years almost that I’ve been waiting for this moment.”

Prior to being confined to his Sacramento home, Joseph served 12 years in a high-security state prison charged with robbery for a crime he committed when he was 22-years-old. Upon his release, Joseph, a legal resident, was taken by U.S. Immigration Customs and Enforcement to a detention center where he spent the next 11 months.

With the onset of COVID-19 during his ICE detainment, Joseph became increasingly concerned with the safety of the facility and the center’s ability to adhere to proper COVID-19 guidelines. Joseph began to organize and mobilize for change within the Mesa Verde ICE Processing Facility.

The former ICE detainee is now working to continue the activism he began within detention walls and attributes his perseverance and pathway to healing to music, art and faith.

Growing up surrounded by music

“I was raised in a musical family,” Joseph said. “Art and music have been a part of my life since,” he paused, “forever.”

Born May 16, 1985 on the Fijian island of Viti Levu, Joseph recalls playing a variety of instruments with his brothers and his father from a very young age. Joseph, the middle child of seven siblings, said music, art, sports and faith were all part of their strict catholic upbringing.

“My dad had a nightclub, so we would go and play at the club Friday afternoons, “Joseph said laughing as he recalled his early keyboard performances. “We would be the only minors in the nightclub and we would play onstage.”

In addition to music, Joseph recalls a strong sense of Indo-Fijian cultural identity and values being instilled in him through traditional song, dance and ceremonies.

RELATED: BHM Playlist: A history lesson on Black music’s impact

When Joseph was 14 years old, his parents applied for U.S. residency, having been sponsored by Joseph’s grandparents who were U.S. citizens. Joseph said the move would be life-changing for him and his family as they left their native land for the same reason so many others do, in search of better opportunities and quality of life.

“Within a matter of weeks we were gone,” Joseph said. “It didn’t actually hit me until the plane was leaving and I was looking out the window watching this island disappear in front of me.”

Shortly after the family immigrated, Joseph’s father was deported back to Fiji after being arrested on charges of domestic violence. Joseph said his father’s deportation left a void in the family structure and without his father’s influence he fell in with the wrong crowd.

“I started losing my way,” Joseph said. “I went from a 4.0 in school to dropping out.”

At the age of 22, Joseph robbed a convenience store and was sentenced to 13 years in prison for second-degree armed robbery in 2007. No one was hurt in the robbery.

Joseph stands on the opposite side of a gate to the pool area that has been closed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic on Wednesday, March 10, 2021 in Sacramento, California. Although he is experiencing the most freedom he has had in years, Joseph is still confined to Sacramento County through the ankle monitor on his right foot that only allows him to travel 50 miles from his home.

Joseph’s experience with incarceration and ICE detention

While incarcerated at High Desert California State Prison, Joseph said he began a healing process through familiar outlets of music and faith. Joseph recalled being welcomed into Native American Sweat Lodge ceremonies that allowed him to process his actions and the anger and frustration left in his father’s absence.

“That really assisted my spiritual growth,” Joseph said, adding that about seven years into his sentence was a true turning point. “After being locked up for so long, I finally started to think clearly, everything just clicked and I had clarity.”

In 2013, Joseph said he was transferred to California State Prison, Solano, for some time where he resumed his education, obtained his GED certificate and went on to take college classes. Eventually, Joseph began teaching music and art classes as well as cultural dances, such as the Haka, which he said helped him “build community” within the prison.

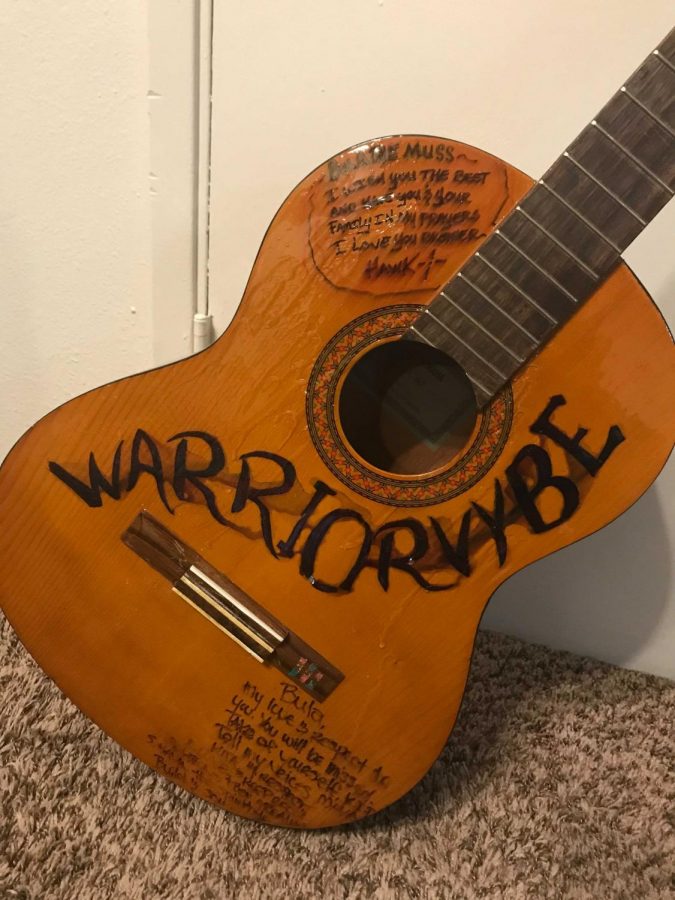

Joseph recalled the first time he saw a guitar on prison grounds. He said it belonged to a fellow inmate who had ordered it through a prison catalog and sold it to him for $100.

“I played it so much I broke all the strings,” Joseph said. “I was so happy to get that connection back to music, that was a big thing for me.”

Joseph said from that moment forward, music was a constant in his rehabilitation. He became the coordinator for music at the prison. He put on concerts in the prison yard and played music in the visiting rooms “to switch up the atmosphere so people weren’t so tense.”

A few years later, Joseph said he was transferred back to High Desert, where he remained until he was granted parole and released May 17, 2019, a day after his birthday. The day before, Joseph said fellow inmates signed his classical acoustic guitar with well-wishes for his release, a release Joseph would find short-lived as he was immediately detained and transferred directly to the for-profit private Mesa Verde ICE Processing Facility in Bakersfield, California.

According to an American Civil Liberties Union research report, the immigration detention system grew exponentially under the Trump administration, exacerbating the prison-to-detention-to-deportation pipeline that disproportionately disadvantages Black and Latinx migrants by expediting them back to their country of origin, oftentimes without proper adjudication.

“That was an unjust transfer,” said Rhonda Rios Kravitz, founding member of the Sacramento Immigration Coalition and CEO of Alianza, adding that Joseph had already served his time and was proved to be rehabilitated.

The Sacramento Immigration Coalition is a grassroots collective of various organizations, including Alianza, that work to further immigrant rights in the Sacramento area by advocating, sharing resources and creating presence in the community, according to its Facebook page.

“Charles engaged while he was in prison in a self-inquiry that led to significant change in his life,” Rios Kravitz said. “Despite hardship and despite suffering, he is there with a positive attitude and willingness to help others.”

Rios Kravitz, a Sac State alumna and former library faculty of 17 years, said the Sacramento Immigration Coalition was approached by Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity shortly after Joseph was detained.

Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity is an Oakland-based statewide organization that is “at the intersection of spirituality and social movements” and unites faith communities to take stands on issues of immigration and incarceration.

“Our role has been to partner with a family or individuals that are impacted by these systems, and accompany them, and in this case, push for a pardon campaign,” said Galatea King, the Northern California regional organizer for Interfaith Movement. King said that Interfaith Movement was first contacted by Joseph’s wife, Shelly Clements, in an effort to raise more awareness of Joseph’s detainment to bring him home to his family.

Rios Kravitz said the partnership of the two coalitions culminated in a petition for pardon from Gov. Newsom, adding that Mayor Darrell Steinberg has written a letter of support on Joseph’s behalf. A letter of support from October is co-signed by 40 organizations including Norcal Resist, the Poor People’s Campaign, Project Rebound, and the Center on Race, Immigration and Social Justice.

Gov. Newsom has not pardoned Joseph as of yet.

Joseph stands on the opposite side of a gate to the pool area that has been closed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic on Wednesday, March 10, 2021 in Sacramento, California. Although he is experiencing the most freedom he has had in years, Joseph is still confined to Sacramento County through the ankle monitor on his right foot that only allows him to travel 50 miles from his home. Joseph said that ever since he was released, the population at Mesa Verde has decreased, thanks in part to an order signed by Northern California District Judge Chhabria that caps the detention center’s population at 26 people per dorm.

Joseph’s activism for human rights of detainees

Ten months into his ICE detainment, Joseph said he and the other detainees began to hear news of COVID-19. Joseph recalled seeing a handwashing video as part of COVID-19 prevention guidelines.

RELATED: Sac State will not require COVID-19 vaccine — student, faculty react

“I’m watching the video, and it just hits me, we can’t do any of those things,” Joseph said, adding that about 100 detainees would share five bars of hand soap on a daily basis.

The ACLU wrote in its 2020 report of detention facilities that it “heard stories of immigrants’ lack of access to proper hygiene and witnessed unsanitary conditions in living units, many of which contained beds, dining, and restroom facilities for up to nearly 100 people all in one room.”

Joseph said he began to call for the release of those detained to preserve the health and safety of the detainees, particularly those with underlying medical conditions. Joseph rallied the support of those detained and wrote a letter urging ICE and Gov. Newsom to release those inside Mesa Verde.

“Our first project with Charles was helping to create a video that we were able to capture with him inside as he was supporting the organizing around COVID-19 [relief],” King said.

She added that Joseph went on to organize a hunger strike when the letter and a subsequent list of demands to the warden went unanswered.

Joseph’s efforts were not unrecognized, however, as he was released with an ankle monitor from Mesa Verde on the third day of the hunger strike April 13, 2020 along with four other detainees. Joseph said that ever since he was released, the population at Mesa Verde has decreased, thanks in part to an order signed by Northern California District Judge Chhabria that caps the detention center’s population at 26 people per dorm.

Now home with his family, Joseph said he still faces the possibility of deportation every day without Gov. Newsom’s pardon, adding that his ankle monitor has yet to be removed. Despite this, Joseph said he focuses on how far he has come and will continue to work for the rights of those incarcerated.

“There can be no exclusion to humane treatment,” Joseph said. “You can’t pick and choose who you treat humanely, that has to be something that’s inclusive and it should be the bare minimum.”

Charles Joseph walks to the edge of his apartment complex’s parking lot to his favorite spot to watch life unfold on Wednesday, March 10, 2021 in Sacramento, California. His scenery from here includes an old wilted oak tree, an empty field that used to be apartments and a Dutch Bros coffee shop with a constantly filled drive-thru line.

Joseph’s fight for rights from the outside

Joseph continues to fight for the rights of those impacted by systems of immigration and incarceration as an official staff member for Interfaith Movement. Joseph said he is a spokesperson and leads the coalition’s support for AB 937, a bill authored by California Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo and backed by a coalition of organizations including Interfaith Movement.

“It stops the transfers from prison and jails to ICE detention centers from happening, which is exactly what happened to Charles,” King said of AB 937.

The bill may be heard in committee March 20.

King said Interfaith Movement’s partnership with Joseph was destined from the beginning, adding that one of Joseph’s initiatives is building engagement within Pacific Islander communities.

“Charles is a voice of a community that’s not always visibilized,” King said. “The impact of these systems on Pacific Islanders, is something that many people don’t see or learn or know about.”

Joseph said he is working to dismantle cultural stereotypes of Asian and Pacific Islander communities to open conversations of healing.

“We have some cultural barriers, that makes it difficult for us to integrate and re-enter the way we should,” Joseph said. “I want to create a movement that allows, mostly those who have been impacted that have been in prison, to come out and be a part of the change.”

King said it is Joseph’s willingness to be open and public about his incarceration and detainment experience that inspires others to process their own experiences.

“I don’t believe people need to be extraordinary to not be deported for a past mistake,” King said. “With Charles, his own journey of healing and transformation is just really powerful and the fact that he also has brought spaces of healing and transformation to others is a gift,” she paused, “and he continues to do that.”

Joseph also continues his own healing through music.

“I’m ready to make music now that I can move around,” Joseph said. “I’ll be in the studio and I’ll be making music soon.”

Correction: March 18, 2021

A previous version of this story incorrectly said that Joseph was transferred to the Mesa Verde ICE Processing Facility instead of being released. He was actually released and then immediately detained by ICE. The story has been corrected to reflect this correction.

Sajdah Abdul-Haqq • Mar 19, 2021 at 6:25 pm

Thank you for sharing.

Emily • Mar 18, 2021 at 10:08 pm

Wow! What a fantastic article. I wish I could hear more about Mr. Joseph and his story and perspective. He seems so genuine and this is so well put, on top of being such an important issue to discuss. Excellent article Ms. Graziosi!! Love that you were able to help give a platform to such a kind soul who was dealt such a rough hand.

Mr Flowers • Mar 17, 2021 at 10:52 pm

This is so insightful and I enjoyed every line. Thank you for sharing all the stories Kat. Tell these guys to get on the clubhouse app and share their stories