Your donation will support the student journalists of Sacramento State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

|  |

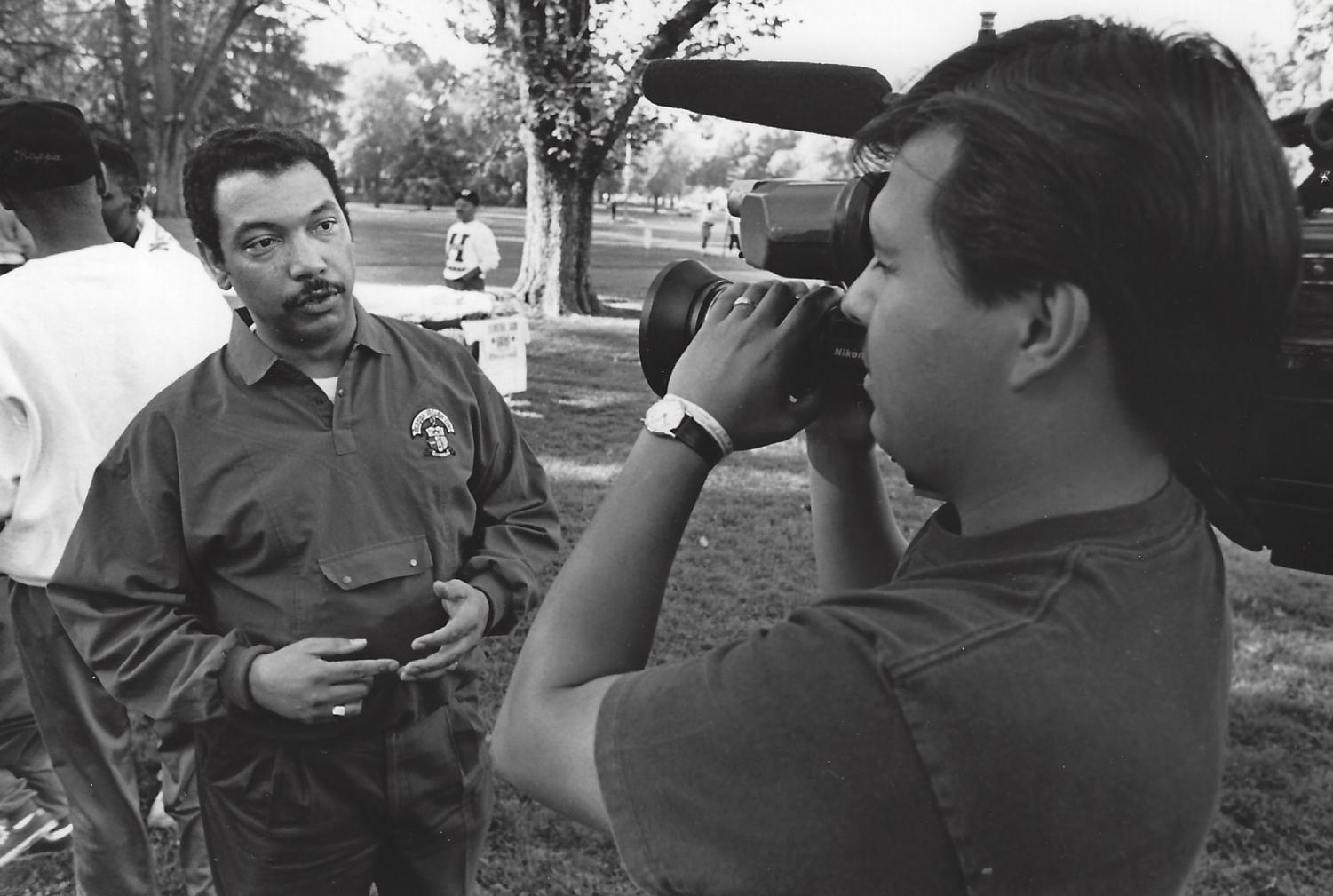

Environmental science professor James W. Reede stands outside the University Union’s COVID-19 vaccine clinic Feb. 8, 2021. Reede was raised by his community activist mother who worked alongside many prominent civil rights activists such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Harry Belafonte and A. Phillip Randolph.

February 26, 2021

Sacramento State environmental science professor James W. Reede said he celebrates Black History Month every February by educating people about Black history and his personal experience with the civil rights movement.

Reede has family ties in Birmingham, Alabama and was born Sept. 14, 1952, in Chicago, Illinois. Reede, 68, said he grew up during a time when Chicago was one of the most segregated cities in the United States. Reede said this gave him a front seat view of the changing civil rights for many minorities in America.

James Reede and Coretta Scott King in 1995 at a dinner celebrating Martin Luther King Day. Reede said he remembers meeting King as a child through his mother’s activism work. Photo courtesy of James Reede.

Reede said he had been familiar with advocating as a child because his mother was a community activist, and that he attributes his mother’s activism as the reason why he has always used his voice to combat discrimination and racism.

Reede’s mother, Jessie Thelma, was a teacher at Drake Elementary School in Chicago alongside the mother of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old who was murdered in a racist attack in 1955. Reede said he remembers attending Till’s open casket funeral Sept. 13, 1955, at the same church that would later be where his father’s service occurred.

Eight years later on a Sunday morning in 1963, Reede recalled the time he answered a phone call from “Aunt Hattie,” his grandfather’s eldest sister. He said she spoke with a very serious tone and asked for an adult.

“She says to my grandfather and my mama: ‘They bombed the church and killed four little girls in Aunt Janie’s Sunday school class,’” Reede said. “See, my Aunt Janie sent them down to the basement to go get Sunday school books and she carried that with her the rest of her life.”

The bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama occurred the day after Reede’s birthday.

“I knew before the Associated Press knew they bombed the church,” Reede said. “Even though it's a bittersweet part of Black history, it is still necessary to know to prevent us repeating it.”

“Black history has to be lived 365 days a year.”

Reede also recalled experiencing biased treatment while attending high school at De La Salle Institute, which Reede said was a “predominantly white Catholic school.”

Despite paying the same tuition as everyone else, Reede said Latino and Black students were not receiving the same treatment that other students got, including free to-and-from school transportation, and that his mother had to speak up in order to get equal treatment for her son and others.

“We all got bus passes because my mama raised hell,” Reede said.

Reede said school was very important to his mother, who had three degrees of her own in chemistry, math and education along with a master’s in education from the University of Chicago.

Besides being a school teacher, Thelma was also the vice chairman of the board of directors for Chicago’s branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Reede said. When Chicago began to desegregate, Reede said Thelma began to attend and host planning meetings for the Black community.

Reede said he’d never forget arriving home from Boy Scout camp on a Saturday in August 1966 only to find a group of prominent civil rights leaders in his home.

“Sitting in my mother's living room was the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Coretta Scott King, Dr. Ralph David Abernathy, A. Philip Randolph, Harry Belafonte and a number of other civil rights stalwarts from the Chicago area,” Reede said.

King was going to give a speech at Nat King Cole Park, across the street from where Reede said his family home resided. At the time, King was leading efforts to battle discrimination and end segregation.

Reede said he thinks having these civil rights leaders as role models made him the person he is today.

“We were in an environment where all of our contacts were Black folks, Black police officers, Black doctors, Black lawyers, Black dentists,” Reede said. “So we had a number of role models to look up to and be mentored by.”

An article in the Sacramento Bee from 2001 featuring James Reede and his work with the Sacramento redistricting project. Reede said he got involved in redistricting to ensure there was equal representation and that districts were drawn equally. Photo courtesy of James Reede.

Even though Reede’s mother was involved in activism and civil rights marches, Reede said his mother forbade him and his brother from attending marches when he was young, as she said that violence could escalate.

“My mother didn’t allow us to go on the marches, because we had to go to school,” Reede said. “She didn’t want to see me get hurt, she protected us, but we saw it all on TV and we knew what was going on, and that’s what got me started.”

Reede said his mother taught him and his brother to respect the police, and took them to the police station located on 48th and Wabash to ensure that “every everybody knew who Thelma Reede’s boys were.”

“We always knew to be on our guard, because the white cops love killing Black folks, - they did back then, they do right now,” Reede said.

Despite being instructed by his mother not to attend demonstrations, Reede recalled another time he defied orders to be able to see the commotion at the 1968 Democratic National Convention four months after the assassination of King, where people were protesting the Vietnam War.

“My uncle told me, ‘Junior, don’t you go downtown’… so me, my brother and my cousins, of course, we go and do what we were told not to do and went down to the demonstrations,” Reede said. “And the police started a riot.”

Reede said the police began to release tear gas in the crowd, and that he saw his brother grab a tear gas canister and throw it back at the police. Reede said he also threw “alley apples,” or bricks, at the police during the riots.

When things began to escalate, Reede said he and his family retreated back to the South side of Chicago and Reede proceeded to go on to work at his summer grocery job.

Reede said his Eagle Scout project was to register people to vote in Chicago, as he was inspired by the Freedom Riders registering people to vote across the country.

“I would have to canvas from 83rd to 87th, from South Park all the way over to State Street,” Reede said. “Ringing every doorbell, running from every dog that got loose.”

After high school, Reede’s activism was put to a halt when he left Chicago, following in his father’s footsteps to enlist in the military. Reede said his father served as a Tuskegee Airman and his great-grandfather was a shoeshiner for a Union Army colonel during the Civil War. According to Reede, his great-grandfather also built many of the Black-owned buildings “in and around Birmingham,” including the 16th Street Baptist Church.

“The country is still just now recognizing the contributions African Americans made and sacrifices defending this country that wouldn't defend them.”

After serving in the military, Reede said that’s when he “got busy.” In San Jose, Reede joined school boards, the housing commission and other community-involved programs.

“If we don’t have an African American on the school board, who’s going to represent our children? If we aren’t on the housing commission, who’s going to say ‘Yeah, that was a discriminatory practice?’” Reede said.

Reede said his way of “getting even” and becoming successful was to read “voraciously.” When he moved to Sacramento, Reede said he was later involved as co-chair in drawing maps of the redistricting project of 1991 for the City Council County Board of Supervisors.

James Shelby, 74, worked on the 1991 redistricting project alongside Reede and has known Reede for approximately 30 years.

Shelby said Reede was “relentless” and worked to make sure Black people in Sacramento were given fair representation and not all placed into one district.

“We tried to look at it in a broader sense, where we had people who would have an opportunity to run and not just be lumped into one African American district,” Shelby said. “That was accepted and we had Lauren Hammond get elected to the city council. It changed the makeup of the city council.”

Reede also served as the first vice president of Sacramento’s NAACP chapter for five years.

Cheryl Reede, 65, said that her husband’s activism has been consistent throughout his life.

“When you see certain policies being implemented that are damaging to communities, you just can't sit back and hope they'll do better, you have to speak up,” she said.

Reede’s wife said it is important to continue speaking up about injustices, and she believes that difficult discussions about revisiting Black history need to be held in order to prevent minimizing what Black people have suffered through.

“We have to implement policies that are fair and equitable, and we just have to do better, we can't have the status quo,” she said.

James Reede at the UNCF walk-a-thon in 1994. This walk-a-thon raised money for Black students attending college, according to the UNCF’s website. Photo courtesy of James Reede.

In May 2003, Reede earned his doctorate in organization and leadership in public resource management and began to teach environmental studies at Sac State that fall semester. He has been teaching environmental science for 18 years, along with a course and curriculum he curated about environmental impact analysis under the California Environmental Quality Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.

Today, Reede said he is the only Black lecturer in the environmental studies department at Sac State. Reede said it’s important for him to continue passing information forward and that he now focuses on teaching his students about the environmental injustices affecting BIPOC communities across the United States.

“My current kick is environmental injustice, not the term environmental justice, but the injustice,” Reede said. “Because it's the people of color who are suffering.”

According to Reede, passing knowledge forward is the bottom line. Reede said it is important to give back when one is endowed with the ability to articulate certain points of view or fight for others.

Tyrell Lassair, a 24-year-old Sac State alumni who graduated with a degree in environmental studies and geography in spring 2020, said he was able to resonate with Reede due to their similar backgrounds.

“Being a Black student in environmental studies, seeing somebody who looks like me was rare. I just expected not to see any Black teachers,” Lassair said. “Up until I met Dr. Reede, I had never had a Black teacher in environmental studies. Being able to see somebody who looks like you, doing something that you're trying to do, is something that's very empowering.”

According to Lassair, Reede would provide perspectives on how environmental decisions affect people in the real world and share stories of his previous community work and personal familial ties with the civil rights movement.

“It's kind of cool to get a perspective from somebody who was old enough to be there,” Lassair said. “He's somebody who's stayed involved since then, so his perspective has evolved so you can identify with what he was saying.”

Reede said he thinks he is a better person because he was able to experience the civil rights movement firsthand.

“Black history has to be lived 365 days a year,” Reede said. “Black history to me means the experience over the years that I’ve been fortunate and misfortune to have witnessed. It means that we need to celebrate the triumphs of the African American community nationwide.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Sacramento State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

|  |