Race and gender bad measure for future students

October 26, 2011

California Gov. Jerry Brown’s veto of Senate Bill 185 this month prevented the reimplementation of universities being able to consider race and gender in student admissions.

While Brown vetoed SB 185 for the wrong reason, it was a good decision for California.

Proposition 209 prohibits the state from giving preferential treatment to individuals or groups on the basis of race or gender. In his veto statement, Brown said the Legislature can’t define Prop 209, but the courts can.

Despite being passed by the voters, Brown supports bypassing the will of the people and wants the courts to reinstate affirmative action.

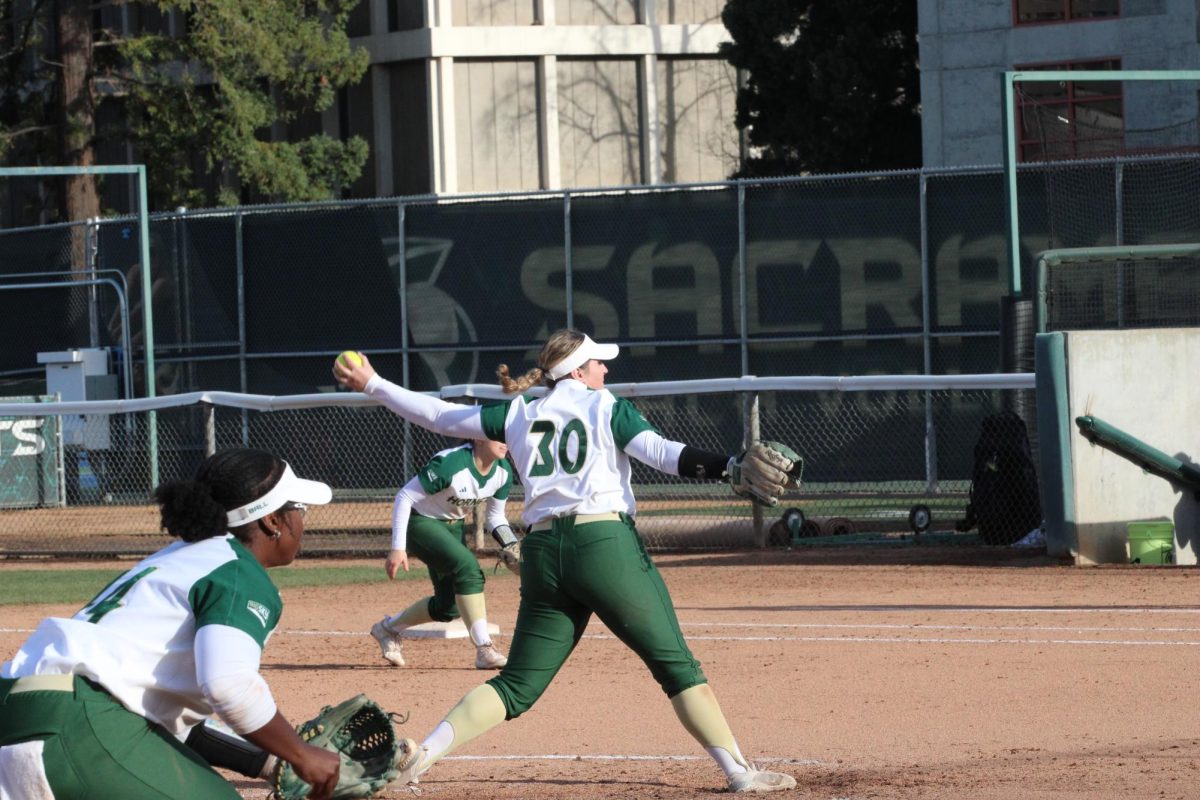

Sacramento State is a perfect example of why affirmative action is not necessary for California and why no governor should ever let it be imposed on students.

Census data from 2010 shows white people make up more than half of the population of California, but only make up 42 percent of undergraduates. The student body consists of more women than men by a wide margin. Undergraduates represent more than 85 percent of the student body and 57 percent of them are women.

Sac State’s policy of accepting students based solely upon their academic success in high school and community college has created an already ideal student body.

Granted, Sacramento is already a melting pot of cultures, but there are people of all backgrounds throughout the state looking at different colleges for different programs. Add foreign exchange students and it is safe to say every university in California will have a noticeable representation of minority students on campus.

If Frozen Caribou State University, located in Igloo, Alaska, needed to drastically increase its ethnic population, affirmative action would be reasonable.

The courts need to leave Prop 209 alone. Creating different standards for admissions based on race ultimately lowers the bar for minorities. It is a disservice for minority students to have to wonder whether they were accepted based on their own merit or to increase some statistics.

“Race doesn’t really dictate a person intellectually,” said sophomore biology science major Kendrick Aragona, who is Filipino.

A student who graduates high school with a C-average should never be given a spot because of his or her race over someone with a B-average.

Admitting students who are not ready to be here puts them in a position to struggle at best and fail at worst.

Getting rejected at first and having to apply to another college or spend more time at a community college might be discouraging, but can be beneficial academically in the long run – not to mention a lot less expensive.

If Brown really wants to increase minority enrollment in universities, he needs to focus on the one problem nearly every student must face: the cost of admission.

Minorities are more likely to come from lower socio-economic backgrounds and go to lower-performing schools. Students living in lower socio-economic situations are less likely to be able to afford tutors, have a computer with Internet access for research at home and be more likely to have to work while in school.

Being poor with college dreams can end with just dreaming for people with unlimited potential but limited bank accounts.

Not all minorities and women are poor, and not every wealthy person applying to college is white and male. Anyone who has persevered despite being financially disadvantaged should get first preference.

“I have three older sisters who all went to college,” said junior communication studies major Connie Moore, who is white and comes from a lower-middle class background. “We all work our butts off to go (to college). My younger brother doesn’t go because of money.”

Having all the administrative policies in the world to help minorities get enrolled won’t help if they can’t afford to be there.

Barring full-ride scholarships or someone who gets to benefit from the Montgomery GI Bill or the Post-9/11 GI Bill, people of all backgrounds have to figure out how they are going to pay for college.

Unless Brown is able to stop the rising cost of attending a university and until lower-income people are no longer getting priced out, his desire to increase minorities on campuses across the state may never happen.